Happy Friday friends,

It’s been a bit of a week over here.

As some of you might have noticed — quite a few of you in fact, judging by the emails — we moved The Pillar back onto Substack as a hosting platform this week. It’s been a project months in the making and not without… wrinkles.

Some of us, me included, got an email this morning telling us our “gift subscription” to The Pillar is about to expire. Sorry about that, please ignore it, it’s just a wrinkle in the system.

Perhaps some of you might be wondering why we would decide to bring our site back to Substack if things were going fine. It’s a fair question.

The reason we were open to the idea is simple enough: many of the things we decided we needed — tiered subscription levels, a revamped website, etc. — weren’t open to us on Substack last year, and they are now. That’s why we were open to it.

As for why we decided to do it…? Well, we decided it was better for our subscribers — namely, you.

In addition to the other stuff we can now do there that we couldn’t before, Substack offers a significantly better commenting system, which a lot of you have told us you want — and we want it too.

Also, and I can’t stress this enough, Substack offers really good customer service for subscribers, certainly compared to us doing it all ourselves. You might think that sounds dull, but it’s actually a big-time commitment to provide customer service to a mailing list of tens of thousands of readers.

The daily minutiae which comes with managing individual subscriber accounts takes a lot of hours. We are a very small team here, just four of us full time, and while Michelle has heroically borne the brunt of the extra work over the last few months, it’s meant less time available for doing actual journalisms, which is what we’re all here to do.

And if you want more of a look behind the curtain, let me tell you about subscriber renewal.

For context, we lose about 10-12% of our paying subscribers as they come up for renewal — and that’s about normal, from what we understand.

A lot of the time, that loss comes down to credit cards expiring, or similar changes to billing details — not to people choosing to cancel their subscriptions.

People whose cards expired have to be followed up with, and encouraged to resubscribe, and it’s often pretty hard to get them to re-enter their new details — even if they want to, that’s a low priority for most of you guys, and we get it. It’s hard to remember to do that.

Other times, subscriber turnover is down to a problem somewhere in the chain between our site, our payment processor, and the bank or credit card company.

Either way, in each case, someone has to figure out what the problem is and try to fix it — that takes a lot of time. And it leaves us with less time to work on the news, while effectively trying to grow our paying subscriber base by 10%, just to stand still.

That keeps me up at night.

So, again, sorry for any hiccoughs over the next few days as we shake down the new backend of our system. Please bear with us; we’re doing this for good reasons and it’s worth the effort.

If you have any trouble using the site, you can hit up Substack for help right here — they’re very good at this kind of thing, as that’s the main reason we put ourselves through the work of migrating the site all over again.

And if you want to help me sleep, consider becoming a paying subscriber. I’m not kidding about how much we need to grow constantly just to stand still — to pay our journalists, and keep our health insurance, for that matter.

If 10% of the tens of thousands of free readers getting this newsletter subscribed at $5 a month, well, I would sleep considerably better than my 18-month-old baby does.

And she’s a good sleeper.

—

The News

The Archdiocese of Milwaukee announced Wednesday that a priest has lost the faculty to hear confessions, after he argued in favor of a bill that would force priests to violate the seal.

The law would seek to compel priests to report evidence or suspicion of child abuse or neglect which they learned in the confessional. Connell, a longtime advocate for victim-survivors of clerical abuse, defended the proposal, despite the total inviolability of the sacramental seal in the Church’s law and doctrine — And I would add, despite there being no evidence, anywhere, after decades of independent reports from governments of all kinds, that the seal has been used to facilitate abuse or contributed to a failure to report.

Archbishop Listecki noted the “understandable and widespread unrest among the People of God” caused by a senior priest arguing for the violation of the sacramental seal and dropped the hammer, stripping Connell of his faculties to hear confessions validly anywhere (except in danger of death).

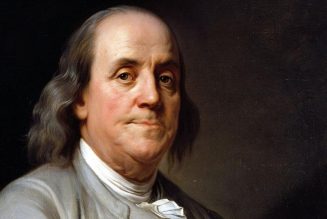

But that’s not all there is to the story, because Fr. Connell is something of an interesting figure.

You can read all about it here.

—

A French bishop has decided to allow a group of French Catholics inside, after they’ve been holding Mass outdoors, on the steps of a chapel, for two years, using the 1962 missal.

The local Catholics started holding Masses outside, on the steps of a hospital chapel, after they were denied a place to celebrate the extraordinary form of the liturgy, and told they didn’t constitute a “stable group” under the provision of Summorum pontificum, the papal motu proprio which regulated the extraordinary form of the Mass prior to Pope Francis’ Traditiones custodes.

The bishop’s decision to accommodate the group is interesting, given that restrictions on the so-called TLM have only tightened since the group began their streetside liturgies. But maybe it isn’t surprising.

Only one in five bishops in France had signed decrees implementing Traditionis custodes. And one recent study found that 20% of French priests were “ordained to celebrate the old missal, and the youth movements that are attached to it are the most fruitful in terms of vocations and commitment.”

Are demographics destiny in France?

—

Three more southern Italian dioceses have suspended the practice of appointing baptismal sponsors — godparents — because, according to the local bishop, the roles have lost their value and been “reduced to a sort of … social custom.”

Several other Italian dioceses have also suppressed the practice for an experimental period of a few years, and the general sense is that godparents are chosen more to reinforce… ahem… family ties, than for any sincere religious purpose.

But how old is the practice of having baptismal sponsors? And what does canon law say they are for, even? You can read our explainer right here.

So far, it is only in Italy that the practice is being ended. It’s possible that bishops in other countries might well decide they have a similar problem, but I haven’t heard any are doing so.

It is what it is. Read all about it.

—

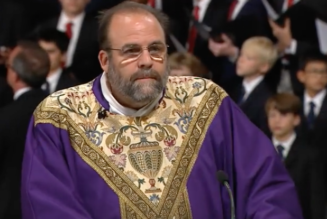

For the moment, nothing seems to have happened after the sostituto at the Secretariat of State told a Vatican court that he’d ordered illegal electronic surveillance of a bank official both in Vatican City and Italy, and that he’d do it again if he wanted to.

Talking to friends around the Vatican, the sense I get is that Archbishop Edgar Peña Parra’s courtroom admission shocked a lot of people, but as with a fart in church, no one wants to be the first to react.

Bottom line: there will be a lot of pressure to avoid any direct action against Peña Parra. For Pope Francis to lose one chief of staff to charges of abuse of office is misfortune, to lose two of them begins to look like carelessness.

But if no action is taken, and the sostituto can defiantly tell a panel of judges that he co-opts law enforcement to spy on anyone who crosses his business deals, that could have serious consequences with international authorities, not least Moneyval and the Italian courts.

You can read my analysis here, and mark my words, this story isn’t going to just go away.

—

This week, Bishop Donald Hying of Madison, Wisconsin, put out a statement expressing his “shock” at the conclusion of the recent synodal way in Germany, which voted for church blessings for same-sex unions, female ordination, and a range of other controversial policies.

You can read the bishop’s statement here, and it is both strongly worded and clearly reasoned.

But it’s a long way from Wisconsin to Westphalia, can the bishop really expect his statement to reach the German bishops? I don’t know, but I’m not sure it matters.

I think Hying, like a lot of bishops, has recognized that the German synodal way is expressly trying to court attention, set an example, and try to inspire imitators around the world.

The German bishops have been upfront about their hopes that their “way” will become the way for the Church — this is why they’ve been so good about translating their entire synodal process into multiple languages in real time.

It seems to me that Hying has a duty to address the German synodal process, not for the Germans’ sake, but as part of his duty to the faithful of his own diocese.

More and more bishops, in the U.S. and further afield, may decide they need to act to correct German attacks on Church teaching and discipline for the sake of their own flocks, which will only fuel the impression of an international rupture opening in the Church.

The only alternative, I think, is for one definitive response to come from Rome and settle the matter for good and all and bring the Germans back into line. But, despite four years of warnings and corrections, Rome has not told the German bishops anything they don’t seem free to ignore.

While I can understand a kind of paralysis of analysis setting in at the Vatican over the German question, and a genuine fear they could provoke the Germans into schism, I think we’re seeing how Roman silence could end up bringing just such a split about.

—

The Church in Germany seems to be something of the elephant in every ecclesiastical room right now.

Whether you’re talking about money, diplomatic influence, bishops and cardinals in key jobs, or, of course, the synodal process, the German influence is strong — perhaps you might even say, disproportionately so.

It’s a very interesting piece.

As Luke notes, far from bossing the game internationally, the last few months have now left the Germans without a bishop serving on Pope Francis’ C9 Council of Cardinals, the preparatory commission for the October synod of bishops, or the leadership of the bishops’ conference of the EU.

Meanwhile, at home, the German Church’s fabulous wealth — derived from state tax funding — has long underpinned their influence abroad. But with German Catholics disaffiliation from the Church in droves, the bishops are approaching a demographic tipping point where all those empty pews start translating into lost revenue.

So is the global influence of the German bishops now a busted flush? Read the whole thing and make your own mind up.

What is the Gospel, anyway?

One of the things which floated across my screen this week was the announcement that the state of Idaho is bringing back executions by firing squad.

A lot of reactions I have seen suggested that this was a regressive step, that it showed America is, as a country, becoming more barbaric in its application of the death penalty. I’m not so sure.

Let’s leave aside questions about capital punishment in general for the moment — I have some complicated views on the subject, which JD assures me are both controversial and wrong, and I will get to them.

Let’s first just talk about lethal injection vs. six guys with rifles.

Frankly, I’d pick the latter if I was on death row. I loathe the lethal injection regime that has become our default mechanism of execution.

For a start, from what I have read, it is far from painless. The best case scenario seems to be that the person feels like he is drowning, and the worst case scenario seems to be that the executioners get the chemical cocktail wrong and the subject feels like he is being burned alive — both sound terrifying and horrendous.

And both, as a simple matter of fact, would appear to take longer and be more painful than being shot.

But beyond the simple mechanics of it being, arguably, a cruel and unusual way of dispatching someone, I hate the medical-liturgical way we go about it: strapping someone to a cruciform table and having a doctor solemnly snuff out a healthy human life, as if death was a kind of “treatment.”

I despise what it says, or suggests, about how we view executions — that we are suppressing an illness in our body politic, rather than meting out justice to a malefactor.

Criminals are not a cancer, they are people, and the way we try to dehumanize them in the process of killing them makes my skin crawl.

A firing squad at least offers no such ambiguity about what is being done and to whom. It is, if nothing else, honest about what an execution is.

—

OK, now I am going to say some stuff about the death penalty in general. Before I do, a disclaimer: These newsletters are where JD and I tell you what we think, and I want to be clear: this is what I think — not what I know, not what I’m immovably convinced of, and not what I am claiming the Church absolutely and obviously says, or what you have to agree with.

This is me thinking out loud.

I’d ask you to take it in that spirit. By all means, tell me why I’m wrong in the comments. JD basically questioned my intelligence and formation as we talked about this yesterday, and it’s cool. I’m a big boy and I am happy to hear persuasive arguments against me, if he finds one.

But I would ask that you do so, and converse with each other, in a spirit of Christian charity. This isn’t Twitter.

—

It seems to me everyone in the Church, at least in the US, used to be pretty settled that we thought the death penalty was, you know, not a good thing.

Under St. John Paul II and then Benedict XVI, the popes of the last few decades have been pretty clear that killing people — even in justice and with due and property authority — is not something we should be happy about. JPII wrote that while capital punishment was a legitimate exercise of state authority, it should be used only “in cases of absolute necessity” which were “very rare, if not practically non-existent.”

Indeed, I thought we all agreed, we should be looking to not execute people whenever possible, and pursue any alternative reasonable and effective means of serving justice and public protection. The bishops in the U.S. have also, for some years, been clear in their opposition to the use of the death penalty — pleading for mercy and advocating for alternatives whenever they can.

But things got messy when Pope Francis amended the Catechism of the Catholic Church in 2018, saying that “the Church teaches, in the light of the Gospel, that the death penalty is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person.”

Francis said some other things before that final sentence, contextualizing his decision with “an increasing awareness that the dignity of the person is not lost even after the commission of very serious crimes” and saying that “more effective systems of detention have been developed, which ensure the due protection of citizens but, at the same time, do not definitively deprive the guilty of the possibility of redemption.”

A lot of people have criticized Francis’ decision, saying that he has effectively reversed the Church’s teaching that the death penalty can be legitimately deployed by the state, and in doing so suggested that the Church’s previous position was an error from the beginning.

People have zeroed in on the pope’s 2017 remarks which said the death penalty is “per se contrary to the Gospel.”

If the pope had meant that the Church had — until him — been wrong about justice and morality, it would be a problem, for sure. Doctrine certainly evolves in the Church, but always in a way that complements and unpacks what came before, without refuting it. And there’s a lot in the pope’s revised wording for the Catechism which I find hard to square.

For example, I admit to reservations about the universality of Francis’ premise and conclusion: that society globally has developed to the point where capital punishment is no longer needed anywhere and as a result is always unjust.

And Francis’ teaching that the death penalty is always “an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person” isn’t without controversy.

But in an address in the United States, in 1999, John Paul II called for Christians to be “unconditionally pro-life” and said that “the dignity of human life must never be taken away, even in the case of someone who has done great evil.”

Now, is there a distinction between saying executions “take away” the “dignity of human life” versus calling them “an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person”? Perhaps, though for myself I don’t reflexively see it as a qualitative one — it’s about degrees vs. absolutes.

The core of the issue is whether the Church, under Francis, still recognizes that the death penalty ever has or can ever be used justly — something the leading lights of American Catholic thought have always agreed upon.

Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, in his famous “Consistent Ethic of Life” speech at Fordham University in 1983, explicitly recognized the legitimate authority of the state to resort to capital punishment. And Cardinal Avery Dulles, writing in 2001, observed that “the Catholic magisterium does not, and never has, advocated unqualified abolition of the death penalty.”

Has Francis rejected the premise that the death penalty ever could be legitimately used? A few people think he has, and a lot more worry that what he has done could be interpreted that way — and, given what that would mean for our understanding of how doctrine can legitimately develop, I can understand why.

Furthermore, the people I know who are wholly relaxed about how the pope went about altering the Catechism on capital punishment tend to be the ones who are also wholly relaxed with saying the Church has always taught error about a whole range of issues (mostly sexual, funnily enough) and who think doctrinal u-turns are great, rather an act of ecclesiological suicide for the Church’s sacred authority.

So given the stakes, I get why some people get very worked up about the subject of capital punishment. But, at the same time, I’ve noticed a trend.

In defending the theoretical legitimacy of the death penalty — with all that entails for the coherence of Church teaching authority — it seems to me that some people who, a few years ago, would have been all aboard the JPII train on being “unconditionally pro-life” have started to talk about the death penalty as if it were a good in itself, rather than a tragic necessity of justice in extreme cases.

In some cases, it seems like it’s being argued that, because the Church teaches that the death penalty can be deployed in some circumstances, and because that teaching is part of what the Church recognizes as the moral law, therefore executions are, per se, part of God’s plan for human flourishing and salvation. That’s where I find myself getting all “Francis” about the death penalty.

—

One of the pope’s more controversial ways of talking about the death penalty is to say it is “contrary to the Gospel.”

So, bearing in mind everything I’ve said above about capital punishment being, in cases, legitimate, and the reasons why this can’t be reversed without equally reversing the Church’s entire claim to possession of immutable truth and teaching authority, I kind of agree with the pope.

Though, I suppose, it depends on what you mean by “the Gospel.”

In fact, that’s what we’ve had some heated disagreement about in The Pillar newsroom in recent days.

If you take “the Gospel” to mean the entirety of the deposit of faith, including the truths of natural law and the full ordering of right justice as recognized and taught by the Church, well I can see why people are confused and concerned by Francis’ statement.

But I am not sold that speaking of “the Gospel” has to always mean “everything the Church teaches and has taught.” I think it is possible, at times, to speak of the Gospel specifically as, well, the Kerygma, the good news of the incarnation, death, and resurrection of Jesus for the salvation of all humanity.

And I don’t think it’s incoherent to speak of “the Gospel” in that sense, or indeed other parts of Church teaching, as pointing us towards something better than merely what is permitted, licit, or even strictly just in all cases.

Christ declined to cast a stone at the adulterous woman, but he didn’t rebuke the crowd while repudiating the entire practice of capital punishment, as he did over divorce. Nor did he excuse the adultery and declare it of no consequence. Instead, he let the crown examine its own conscience and ordered the woman to sin no more.

It seems to me Christ modeled what God says of Himself in the Scriptures: that He takes no delight in the death of a sinner, but wishes to see them repent and live. Is that, too, not the Gospel by which we are called to model ourselves and the justice we work among ourselves?

If the abstract justice of the death penalty is established in the basic moral law, and its specific just application is conditioned by the circumstances of time and place (both of which I believe), are we not called by “the Gospel”, however broadly or narrowly you want to use the term, to work for the elimination of those circumstances?

Now, does every sinner repent? No. Indeed, as Cardinal Ranjith’s crime bosses show, some continue to take innocent lives even when incarcerated, and leave society with no obvious alternative to protect itself from them.

But if every execution isn’t “contrary to the Gospel,” can we not agree that it is at least a falling short of the Gospel, a failure of repentance or mercy or both?

Are we comfortable saying “the Gospel” proclaims the good news about firing squads? If not, I think we can admit that Pope Francis may have a point, even while holding absolutely to the immutability of what the Church has always taught and the questions raised by his phrasing.

Again, I’m just thinking this through here. No one has to agree with me. And everyone is free to tell me I’m wrong in the comments. I’d welcome being talked around; otherwise, I’m plenty used to being both right and in the minority opinion.

See you next week,

Ed. Condon

Editor

The Pillar

Comments 42

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews