By Clement Harrold

Many skeptics and even some Christians struggle with the idea that the Bible not only fails to condemn slavery, but actually seems to justify its existence in places. What are we to make of the Mosaic Law’s detailed prescriptions for how slaves are to be treated, for example? And how about St. Paul’s injunction to slaves to “obey in everything those who are your earthly masters” (Col 3:22)? If the Bible is the inspired Word of God, how can it be so complicit in something as evil as slavery?

There are a number of points worth making here. At a basic level, we need to remind ourselves that the kinds of slavery sanctioned by Moses in the Old Testament are nothing close to the chattel slavery which plagued the New World following the discovery of the Americas. Under that system, slaves were routinely kidnapped from their homelands and subjected to appalling conditions. In the eyes of the law, they were mere pieces of property, meaning their owners could do with them whatever they liked.

In stark contrast to this perverse system of cruelty, the Old Testament allowance for slavery is more akin to indentured servitude than anything else. When families fell into serious debt—a common occurrence in the Ancient Near East—the individuals involved would sometimes be forced to sell their labor for a fixed period of time so as to repay what they owed.

This may sound harsh to us, but it is worth noting just how morally advanced the Israelites were for their time. For starters, God established numerous laws aimed at safeguarding the poor and trying to prevent them from falling into destitution in the first place. Farmers were required not to reap the corners of their fields, for example, in order to allow the poor and foreigners to take the leftover crops (see Lev 23:22).

Similarly, ancient Israel possessed an extraordinarily progressive system for releasing slaves from their debts: every seven years Hebrew servants were to be set free, regardless of how much they still owed to their masters (see Ex 21:2; Dt 15:1). Other safeguards also existed, such as laws against killing a slave (see Ex 21:2), against causing a slave serious physical harm (see Ex 21:26-27), and against returning runaway slaves (see Dt 23:15-16). Likewise, kidnapping a person with an eye to enslaving them was a crime punishable by death (see Ex 21:16).

Admittedly, foreign slaves were subject to somewhat harsher conditions than their Hebrew counterparts, but even here God took steps to mitigate abuses. As He repeatedly reminds His people in the law, “The stranger who sojourns with you shall be to you as the native among you, and you shall love him as yourself” (Lev 19:34). In a profound sense, the Israelites are instructed to love foreigners as their own kin! On this basis, God is able to instruct the people to “have one law for the sojourner and for the native” (Lev 24:22).

The Old Testament scholar Paul Copan reminds us that Israel’s slavery laws were about regulating an imperfect system, not idealizing it. This is an important point. The moral logic of the Bible is oftentimes one which condescends to human weakness, but it never settles there. Pope Benedict XVI captured this point well in his Apostolic Exhortation Verbum Domini:

[There are] those passages in the Bible which, due to the violence and immorality they occasionally contain, prove obscure and difficult. Here it must be remembered first and foremost that biblical revelation is deeply rooted in history. God’s plan is manifested progressively and it is accomplished slowly, in successive stages and despite human resistance. (§42)

Always the aim of the law is to summon fallen human beings to a higher order of love. Along the way, God draws His people through continual stages of moral development, making concessions where necessary to their “hardness of heart” (Mt 19:8), but all the while working to “correct little by little those who trespass” (Wis 12:2).

In response to this, sometimes critics will make the point that even the New Testament fails to condemn slavery outright. The objection is a flawed one, however, because there are plenty of evil activities which the New Testament fails to call out explicitly. We can think here of the Greco-Roman practice of infant exposure, for example, or the gladiatorial games. Rather than offering a step-by-step critique of every wicked practice common to the Roman Empire and its surrounding cultures (which would be a very long list!), what the New Testament provides instead is a transformative understanding of the dignity of the human person and of society.

Building on the idea that all human beings—including slaves (see Job 31:14-15)—share in the imago Dei (see Gen 1:27), the New Testament challenges slave owners to treat those under their authority “no longer as a slave but more than a slave, as a beloved brother” (Phil 16; see also Col 4:1). In this radical new vision, civilization is reshaped from the inside out. As Benedict XVI observed, “Even if external structures remained unaltered, this changed society from within” (Spe salvi, §4). The bonds of Christian brotherhood now transcend all socio-political ties: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Gal 3:28; see also Col 3:11).

Here the proof is in the pudding. The critics can say what they like, but the historical reality is that it was Christianity which succeeded in making the institution of slavery all but disappear for over a millennium, and it was Christianity which abolished infanticide, gladiator games, crucifixion, and the like. Moreover, when wicked individuals and corporations began to reintroduce slavery in the 16th and 17th centuries, it was the Christian abolitionist movement that eventually brought them down.

We should remember, too, that the earliest Christians were routinely mocked for promoting a religion composed of women and slaves. From this we can infer that those living on the margins of the Roman Empire saw something different in this new movement, and they felt compelled by it. Here was a religion which had the audacity to declare that Almighty God had Himself died a slave’s death on a tree (see Phil 2:7). In this ultimate act of solidarity, the intrinsic worth and dignity of every slave would forever be exalted.

Further Reading:

Pope Benedict XVI, Verbum Domini: Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation on the Word of God in the Life and Mission of the Church (2010).

Paul Copan, Is God a Moral Monster?: Making Sense of the Old Testament God (Baker Books, 2011)

Mark Giszczak, Light on the Dark Passages of Scripture (Our Sunday Visitor, 2015)

Scott Hahn and John Bergsma, “What Laws Were Not Good: A Canonical Approach to the Theological Problem of Ezekiel 20:25-26.” Journal of Biblical Literature 123.2 (2004), pp. 201-218.

Trent Horn, Hard Sayings: A Catholic Approach to Answering Bible Difficulties (Catholic Answers Press, 2016)

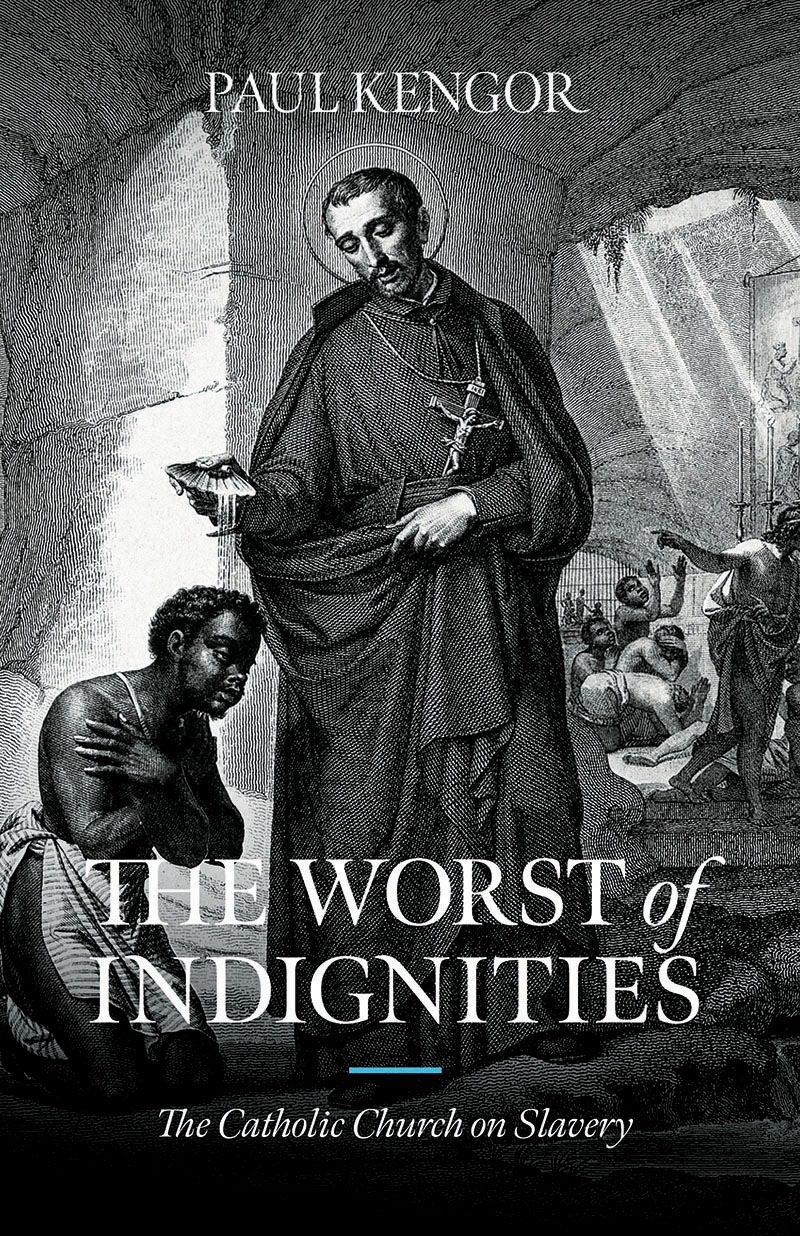

Paul Kengor, The Worst of Indignities: The Catholic Church on Slavery (Emmaus Road Publishing, 2023)

Clement Harrold earned his master’s degree in theology from the University of Notre Dame in 2024, and his bachelor’s from Franciscan University of Steubenville in 2021. His writings have appeared in First Things, Church Life Journal, Crisis Magazine, and the Washington Examiner.

You Might Also Like

Many Americans think of slavery as their nation’s original sin. But in truth, slavery has involved peoples and cultures and countries far beyond the United States. Slavery is as old as human history itself.

And yet, the one living institution that has condemned slavery longer and more consistently than any other is the Roman Catholic Church.

In The Worst of Indignities: The Catholic Church on Slavery, bestselling author Paul Kengor shines a light on:

- The record and biblical roots of the Church’s teaching on slavery

- The efforts of individuals and institutions within the Church to not only bring about freedom for enslaved people but to care for their physical and spiritual needs

- The stories of former slaves whose lives of exemplary holiness have placed them on the path of sainthood

At a time when race relations are so bitter, we need the clarifying truth to unite us all. The story of the Roman Catholic Church’s bold and divine opposition to slavery is one unknown to Catholics and non-Catholics alike. It is time for that story to be told.