The outbreak of Covid-19, a coronavirus-caused illness that originated in Wuhan, China, and has since spread to most of the world, is one of the most serious public health crises in decades. It has spread far wider than Ebola did in 2014, and the World Health Organization has designated it a pandemic. Johns Hopkins’s tracker is worth bookmarking with case number counts in the US and worldwide as the crisis progresses.

The situation on the ground is evolving incredibly quickly, and it’s impossible to synthesize everything we know into clean, intelligible charts. But we do know a fair bit about how bad the outbreak is, what the disease does, and what controlling and ultimately ending the outbreak will look like.

With that in mind, here are nine charts that help explain the Covid-19 coronavirus crisis.

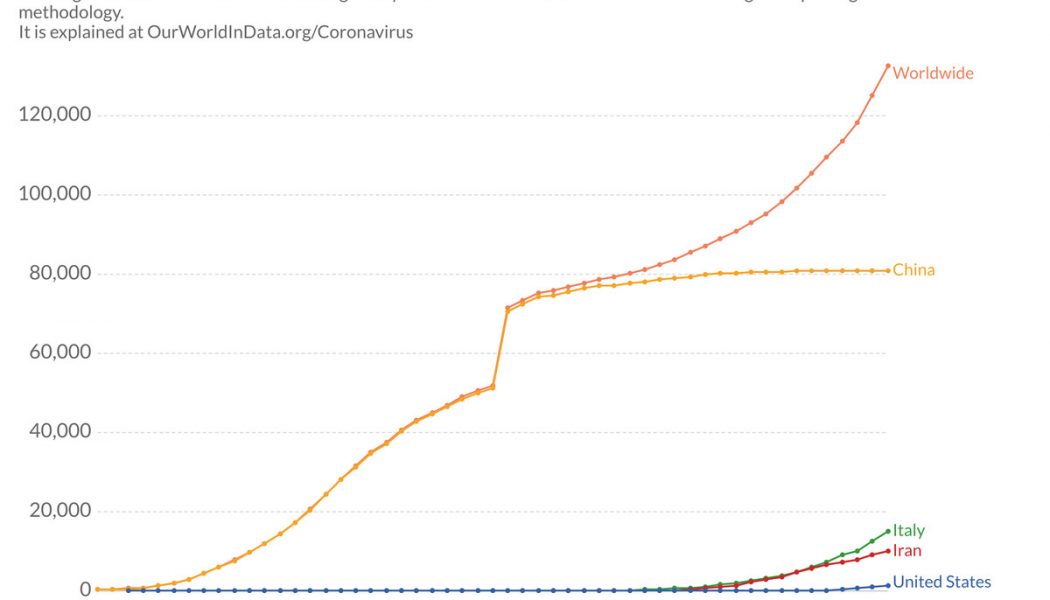

1) The virus is spreading rapidly

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19805339/total_cases_covid_19_who.png)

The Covid-19 caseload has risen rapidly day to day, but here’s where things stood as of March 13. Many of the reported cases are still from the earlier peak in China. But while the number of new cases in China has fallen, the number of new international cases is rising, indicating that the epicenter of the problem has shifted from China to new places like Europe and the United States.

Note that the huge spike in new cases was due to improved data reporting from China; there was not one particularly bad day in the middle of February.

2) Know the symptoms

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19782405/Coronavirus_Symptoms___WHO_joint_mission_2.png)

The symptoms of Covid-19 vary from case to case, but the most common ones in China, from February data, are fever and dry cough (which are each seen in a majority of cases), fatigue, and sputum (the technical term for thick mucus coughed up from the respiratory tract).

If you have a fever and dry cough, that could be a good reason to contact a health professional and get yourself tested if possible.

3) Death rates in China have declined over time

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19769372/Screen_Shot_2020_03_05_at_8.49.26_AM.png)

One glimmer of hope in this story is that Chinese medical authorities appeared to get better at treating infections and preventing death as the outbreak proceeded. “Even the first and hardest-hit province, Hubei, saw its death rate tumble as public health measures were strengthened and clinicians got better at identifying and treating people with the disease,” Vox’s Julia Belluz explains.

The rate didn’t go down on its own; China took drastic, even authoritarian measures to lock down affected areas and contain the virus’s spread so that the medical system was not overwhelmed.

4) Older people in China have been at the greatest risk of dying from Covid-19

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19788825/estimate_case_fatality_hubei_age.jpg)

The Spanish flu of 1918-’19, the most horrific pandemic in modern times, focused mainly on the young. It had biological similarities to a flu pandemic in the 1830s that gave some older people in the 1910s limited immunity.

Covid-19 is not like that. So far, deaths in China have been concentrated among older adults, who have weaker immune systems on average than younger people and have a higher rate of chronic illness. People of all ages with chronic medical conditions are also at higher risk. The risk of death is real for younger people as well, but older people are most at risk.

5) This is much more severe than an ordinary flu

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19782413/Covid_19_CFR_by_age_vs._US_Seasonal_Flu_3.png)

It is tempting to compare Covid-19 to a more familiar disease: the seasonal flu. After all, the flu also has mild symptoms for most people, and can be dangerous and lethal among vulnerable populations like the elderly. President Trump even made this comparison recently.

But as the case fatality data shows, there’s no real comparison. About 6 percent of people 60 or older infected with Covid-19 die, according to the data from China we have so far; that’s over six times the fatality rate in the US for older people infected with the flu. The overall Covid-19 fatality rate may be 12 to 24 times the flu death rate. (Estimates for the fatality rate for Covid-19 vary, and they vary by region depending on response to the outbreak.)

6) Experts also think Covid-19 is more contagious than the ordinary flu

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19751074/Viruses_with_corona_update_covid.jpg)

There’s another way that Covid-19 is a tougher adversary than the seasonal flu: Its R0 (“R nought”) is over 2, indicating that it’s more contagious than the typical flu. R0 estimates the number of people an average infected person spreads the disease to. “R0 is important because if it’s greater than 1, the infection will probably keep spreading, and if it’s less than 1, the outbreak will likely peter out,” the Atlantic’s Ed Yong explains. Covid-19’s R0 is substantially higher than 1, giving more reason for concern.

7) Spending on airlines, hotels, and cruises is collapsing

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19780411/travel_sales_change_desktop.png)

Warnings to avoid crowds, and cancellations of major gatherings like conferences and parades, have put a damper on travel in the US, and the consequences for airlines have been dire. According to Earnest Research, spending on airlines fell 16.5 percent in the last week of February relative to a year prior. Cruises have seen a similar dip, while hotels are only now starting to see sales mildly decline.

It’s unlikely that the economic impact will stay limited to the hospitality industry, as social distancing leads people to avoid coffee shops, restaurants, gyms, bars, etc.

For more, see Rani Molla’s write-up for Recode.

8) The US is not testing enough people

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19787964/covid_19_testing_per_capita.jpg)

The Trump administration’s slow rollout of testing for coronavirus has become something of a national scandal, and it’s easy to see why when you compare the US testing rate to that of other affected countries. South Korea stands out for its rapid rollout of extensive testing, including through innovative drive-through testing programs.

Drive-through testing is being piloted in some parts of the US, like New Hampshire, but we still have a long way to go before we match South Korean and Chinese testing levels.

9) Why canceling events and self-quarantining is so important

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19780273/flattening_the_curve_final.jpg)

Covid-19 has quickly made large-scale gatherings and conferences unpopular if not socially frowned upon. This change arrived quickly, and may seem jarring, but it’s easier to see the logic when you understand the theory behind this kind of “social distancing” policy. The key is to “flatten the curve”: slowing the rate of increase in infections so that you spread out the cases, even if the total number doesn’t change.

Flattening the curve slows the rate at which new cases arrive in hospitals, easing the burden on health care infrastructure and improving the odds that individual patients will survive.

Read more from Eliza Barclay and Dylan Scott here.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter and we’ll send you a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling the world’s biggest challenges — and how to get better at doing good.

Future Perfect is funded in part by individual contributions, grants, and sponsorships. Learn more here.