I spent much of yesterday reading this book, which means I spent much of yesterday wondering…how did she?….and feeling thoroughly inadequate.

Isabella Bird (1831-1904) was an Englishwoman who was the child of an Anglican curate, was educated at home, had health challenges as a child and young woman…and then spent most of her adult life traveling the world.

Here’s the list of her books at Gutenberg.

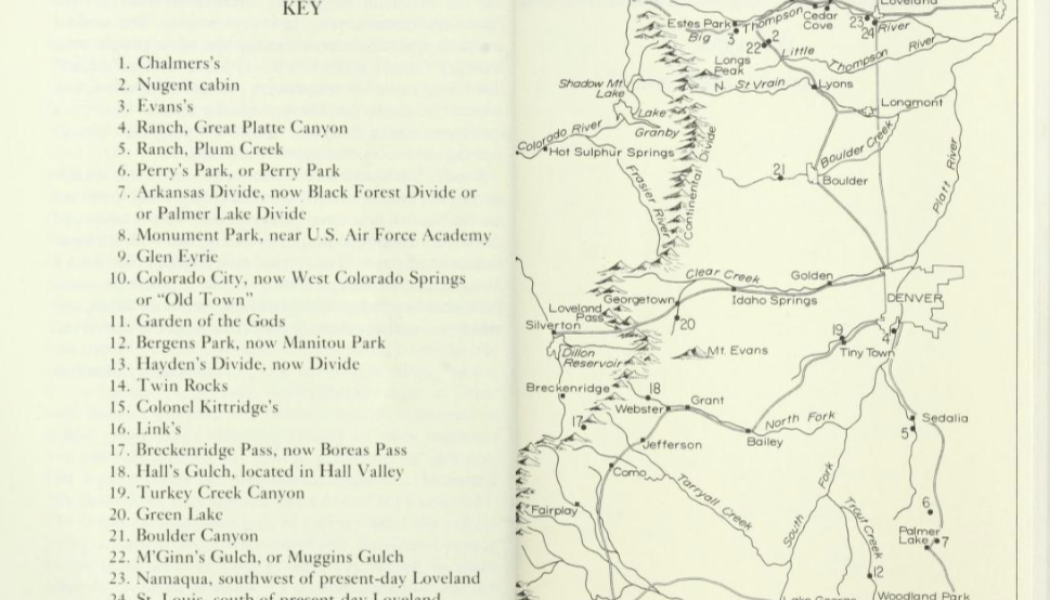

In 1873 – so at the age of 41 – on the way from Hawaii to England, she made her way from San Francisco to Colorado, where she spent a few months exploring, mostly on her own on horseback in the late fall and early winter. A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains is the account of that time, told through letters to her sister. The book was a sensation and, according to this, an important factor in making Bird the first female member of the Royal Geographical Society.

So remember: mostly on horseback, mostly alone, in the late fall and early winter. So, snow.

Of course, she wasn’t going about this blind. The area was wild, but settled, and she was given guidance, direction and the locations of places she could stop – and during this era, every person who lived in any kind of shelter along these trails and roads was expected to receive travelers.

Nonetheless. It’s a fascinating account of:

- Colorado territory during the era

- Other areas of the West – most of which she doesn’t think much of, with the exception of the area around Truckee, California. She has particular disdain for the towns of Wyoming, although she doesn’t have much love for Colorado’s settlements, either. But Wyoming, to Bird = the worst.

- How people lived and survived during the time in this area and the variety of settlers: Civil War veterans, English folk, Germans, many people who’d come from the East for their health, particularly consumptive patients, and indigenous peoples.

Speaking of the last, Bird, like most Europeans visiting the United States in the 19th century, is direct and harsh in her observations of how Americans treated subjugated populations, here the Native Americans. She often alludes to the damage of hunting the buffalo to extinction, the conflicts over land that always end to the native peoples’ disadvantage, and the corruption of the agencies charged with dealing with the issue:

The Indian Agency has been a sink of fraud and corruption; it is said that barely thirty per cent of the allowance ever reaches those for whom it is voted; and the complaints of shoddy blankets, damaged flour, and worthless firearms are universal. “To get rid of the Injuns” is the phrase used everywhere. Even their “reservations” do not escape seizure practically; for if gold “breaks out” on them they are “rushed,” and their possessors are either compelled to accept land farther west or are shot off and driven off. One of the surest agents in their destruction is vitriolized whisky. An attempt has recently been made to cleanse the Augean stable of the Indian Department, but it has met with signal failure, the usual result in America of every effort to purify the official atmosphere. Americans specially love superlatives. The phrases “biggest in the world,” “finest in the world,” are on all lips. Unless President Hayes is a strong man they will soon come to boast that their government is composed of the “biggest scoundrels” in the world.

- The perspective and experience of a woman in the late 19th century.

In regard to the last point: I hate to break it to you, but the history of women is not a history of “housewives” (in the contemporary sense) tending to the hearth while the men worked “outside the home” until Liberation Day arrived a few decades ago. With the exception of the leisured classes, everyone worked, all the time, somewhere. Until the Industrial Revolution and continuing in areas less directly impacted by it, “work” was an organic activity that certainly had a gendered component, related to childbearing and tending as well as physical strength, but was on the whole just…life. And it (work) was demanding, no matter who you were. It was not to a woman’s advantage to be a delicate flower.

Which is all to say that Bird’s presence and way on this journey was not received as a revolutionary violation of gender norms. If anyone warned her not to embark on a particular path it was because, well, there was probably a blizzard coming, Ma’am…and not because she was a woman. In fact, during her lengthy stay in Estes Park, she was regularly asked to help with cattle round-ups and such because of her skill – this 40+ year old Englishwoman, riding, as she put it, in her “Hawaiian riding costume” out there in the mountains.

Her ascent (with three companions) of Longs Peak:

SCALING, not climbing, is the correct term for this last ascent. It took one hour to accomplish 500 feet, pausing for breath every minute or two. The only foothold was in narrow cracks or on minute projections on the granite. To get a toe in these cracks, or here and there on a scarcely obvious projection, while crawling on hands and knees, all the while tortured with thirst and gasping and struggling for breath, this was the climb; but at last the Peak was won. A grand, well-defined mountain top it is, a nearly level acre of boulders, with precipitous sides all round, the one we came up being the only accessible one.

It was not possible to remain long. One of the young men was seriously alarmed by bleeding from the lungs, and the intense dryness of the day and the rarefication of the air, at a height of nearly 15,000 feet, made respiration very painful. There is always water on the Peak, but it was frozen as hard as a rock, and the sucking of ice and snow increases thirst. We all suffered severely from the want of water, and the gasping for breath made our mouths and tongues so dry that articulation was difficult, and the speech of all unnatural.

From the summit were seen in unrivalled combination all the views which had rejoiced our eyes during the ascent. It was something at last to stand upon the storm-rent crown of this lonely sentinel of the Rocky Range, on one of the mightiest of the vertebrae of the backbone of the North American continent, and to see the waters start for both oceans. Uplifted above love and hate and storms of passion, calm amidst the eternal silences, fanned by zephyrs and bathed in living blue, peace rested for that one bright day on the Peak, as if it were some region

Where falls not rain, or hail, or any snow,

Or ever wind blows loudly.We placed our names, with the date of ascent, in a tin within a crevice, and descended to the Ledge, sitting on the smooth granite, getting our feet into cracks and against projections, and letting ourselves down by our hands, “Jim” going before me, so that I might steady my feet against his powerful shoulders. I was no longer giddy, and faced the precipice of 3,500 feet without a shiver. Repassing the Ledge and Lift, we accomplished the descent through 1,500 feet of ice and snow, with many falls and bruises, but no worse mishap, and there separated, the young men taking the steepest but most direct way to the “Notch,” with the intention of getting ready for the march home, and “Jim” and I taking what he thought the safer route for me—a descent over boulders for 2,000 feet, and then a tremendous ascent to the “Notch.” I had various falls, and once hung by my frock, which caught on a rock, and “Jim” severed it with his hunting knife, upon which I fell into a crevice full of soft snow. We were driven lower down the mountains than he had intended by impassable tracts of ice, and the ascent was tremendous. For the last 200 feet the boulders were of enormous size, and the steepness fearful. Sometimes I drew myself up on hands and knees, sometimes crawled; sometimes “Jim” pulled me up by my arms or a lariat, and sometimes I stood on his shoulders, or he made steps for me of his feet and hands, but at six we stood on the “Notch” in the splendor of the sinking sun, all color deepening, all peaks glorifying, all shadows purpling, all peril past.

“Jim” had parted with his brusquerie when we parted from the students, and was gentle and considerate beyond anything, though I knew that he must be grievously disappointed, both in my courage and strength. Water was an object of earnest desire. My tongue rattled in my mouth, and I could hardly articulate. It is good for one’s sympathies to have for once a severe experience of thirst. Truly, there was

Water, water, everywhere,

But not a drop to drink.Three times its apparent gleam deceived even the mountaineer’s practiced eye, but we found only a foot of “glare ice.” At last, in a deep hole, he succeeded in breaking the ice, and by putting one’s arm far down one could scoop up a little water in one’s hand, but it was tormentingly insufficient. With great difficulty and much assistance I recrossed the “Lava Beds,” was carried to the horse and lifted upon him, and when we reached the camping ground I was lifted off him, and laid on the ground wrapped up in blankets, a humiliating termination of a great exploit. The horses were saddled, and the young men were all ready to start, but “Jim” quietly said, “Now, gentlemen, I want a good night’s rest, and we shan’t stir from here to-night.” I believe they were really glad to have it so, as one of them was quite “finished.” I retired to my arbor, wrapped myself in a roll of blankets, and was soon asleep.

When I woke, the moon was high shining through the silvery branches, whitening the bald Peak above, and glittering on the great abyss of snow behind, and pine logs were blazing like a bonfire in the cold still air. My feet were so icy cold that I could not sleep again, and getting some blankets to sit in, and making a roll of them for my back, I sat for two hours by the camp-fire. It was weird and gloriously beautiful. The students were asleep not far off in their blankets with their feet towards the fire. “Ring” lay on one side of me with his fine head on my arm, and his master sat smoking, with the fire lighting up the handsome side of his face, and except for the tones of our voices, and an occasional crackle and splutter as a pine knot blazed up, there was no sound on the mountain side. The beloved stars of my far-off home were overhead, the Plough and Pole Star, with their steady light; the glittering Pleiades, looking larger than I ever saw them, and “Orion’s studded belt” shining gloriously. Once only some wild animals prowled near the camp, when “Ring,” with one bound, disappeared from my side; and the horses, which were picketed by the stream, broke their lariats, stampeded, and came rushing wildly towards the fire, and it was fully half an hour before they were caught and quiet was restored. “Jim,” or Mr. Nugent, as I always scrupulously called him, told stories of his early youth, and of a great sorrow which had led him to embark on a lawless and desperate life. His voice trembled, and tears rolled down his cheek. Was it semi-conscious acting, I wondered, or was his dark soul really stirred to its depths by the silence, the beauty, and the memories of youth?

We reached Estes Park at noon of the following day. A more successful ascent of the Peak was never made, and I would not now exchange my memories of its perfect beauty and extraordinary sublimity for any other experience of mountaineering in any part of the world. Yesterday snow fell on the summit, and it will be inaccessible for eight months to come.

This is only a glimpse. It’s a delightful, fascinating read.