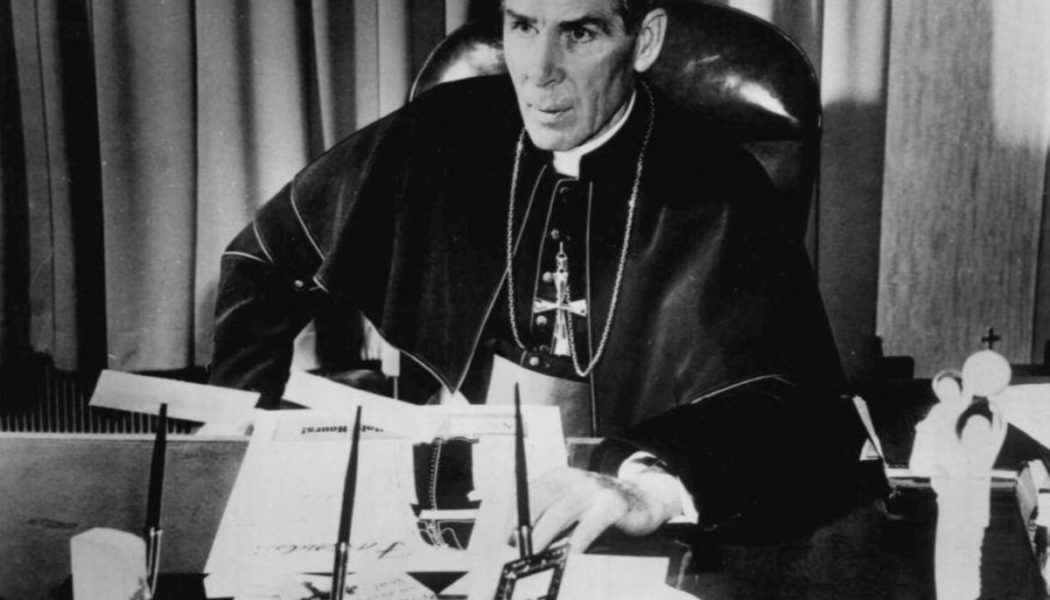

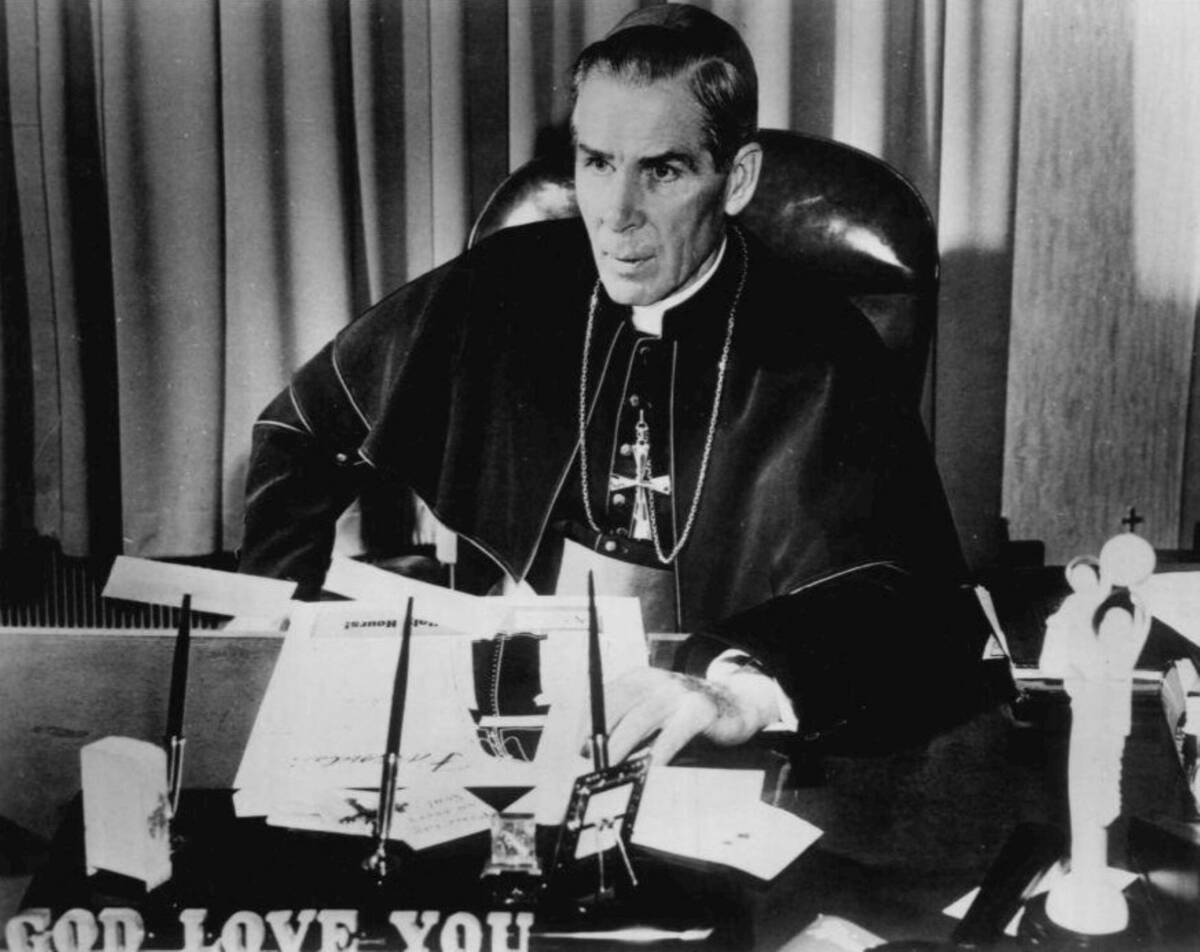

I previously outlined what might be considered the philosophy of education of Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen. That piece detailed some of the bishop’s impressive legacy and unpacked the philosophy that animated his teaching career and his commitment to Catholic education. Having looked closely at his principles, I would like to turn now to Sheen’s praxis. What follows will highlight three of Sheen’s pedagogical practices that made him an extraordinarily successful scholar and teacher and—if I may be so bold—the premier Catholic communicator of the American Church in the twentieth century. Believing firmly that we all have something to learn from the good bishop about teaching and handing on the faith, I hope what follows here serves as an opportunity for inspiration and reflection for those who, like Sheen, have committed themselves to the Church’s hard work of education, evangelization, and catechesis.

1. Preparation, Preparation, Preparation

In 2015, Thomas Reeves released an unpublished conclusion to the excellent bfiography he authored on Sheen thirteen years earlier. He entitled the conclusion “Living Intensely”—a most apropos way of describing Sheen’s manner of life.[1] Those close to Sheen knew well the kind of intensity with which he lived. As the title of his autobiography alludes, Treasure in Clay, imagery adapted from St. Paul (cf. 2 Cor 4:7), Sheen believed that on the day of his ordination there had indeed been placed within the clay of his own earthy existence an infinitely valuable treasure. The only appropriate way of responding to the tremendous gift of his vocation and talent, he thought, was to live intensely: to work as hard as he could, for as long as he could, so that he might share the Gospel and instruct in the Catholic faith as many as possible.

Sheen honed an extraordinary work ethic, one that had him keeping “nineteen-hour days, seven days a week.”[2] Sheen himself admits that he “was brought up on the ethic of work”[3] ingrained in him by his parents as child on the Sheen family farm.[4] A 1959 newspaper article described him in the following way:

The public sees Bishop Sheen as a charming and gay personality, but they may be surprised to learn that he leads an almost ascetic life, that he spends most of his free time working in his study, that he neither smokes nor drinks, never relaxes by taking a day off, eats only enough for nourishment, takes a vacation every decade, never attends the theater, and rarely goes out for a social evening.[5]

Alluding to his own view on work in his 1939 book, Victory Over Vice, Sheen writes:

We need have no undue fear for our health if we work hard for the kingdom of God. God will take care of our health if we take care of His cause. In any case, it is better to burn out than to rust out. Burning the candle at both ends for God’s sake may be foolishness to the world, but it is a profitable Christian exercise—for so much better the light. Only one thing in life matters: being found worthy of the Light of the World in the hour of his visitation.[6]

Sheen praises God that hard work was a habit that he never surrendered because it applied well when he entered the realm of academia and public speaking.

If Sheen’s behind-the-scenes work as a teacher and preacher communicated any one maxim it might have been: preparation, preparation, preparation. Sheen felt a deep moral responsibility as a professor to come to class extraordinarily prepared. This, coupled with his astounding oratory skills, is, I think, what made him a professor and teacher of the highest caliber, and thus one of the most popular university instructors during his years at Catholic University.

While a natural speaker, Sheen had to learn—primarily through trial and error—how to lecture and teach at the university level. Always wishing to be at his best before his students, Sheen labored with great intensity over each lecture. Before composing even a single line of a lecture, Sheen would pour over primary source texts for hours. Sheen admits that he would spend three months in London each summer preparing for the courses he was scheduled to teach during the year. Early on, Sheen formulated a rule for himself: a minimum of six hours of preparation for every one hour of class lecture.[7] When it came time to finally deliver the lecture, Sheen wanted the material to be fully his—belonging not to his lecture notes, but to be so totally his that not a single point could be forgotten.

After days—sometimes even weeks—of painstaking preparation and research, Sheen would compose his lecture as he would every lecture of his life. He tells us:

I learned to lecture from the inside out, not from the outside in. I did not learn the lecture by reading over the notes from my research. I would write out from memory my recollection of the points. Then I would check with the research to see how well I had absorbed the points. That paper on which I had first summarized would be torn up. One new plan after another would be drawn up and destroyed. I would repeat the process over and over again so that I was not allowing a piece of paper to dictate to my living mind. . . . The number of times that I would write out or even talk these points to myself would vary with the difficulty of the matter or with my memory. Finally, I would reach a point where the material was mine. It was like digested food, not food on the shelf.[8]

In his biography on Sheen, Reeves includes delightful anecdotes from students who studied under Sheen at the Catholic University of America. Here is one such example:

“He worked his students!” exclaimed one CUA graduate. “His required reading lists were awesome, but we knew that he had read all the works he recommended and we realized that if we were to get anything out of his courses we should do the same.” Said another, “You’d no more think of raising a hand in one of his classes than of telling the sun to stop shining for a minute. Nor can I honestly say you’d want to. He was that spell-binding a teacher.” Robert Paul Mohan, who studied under Sheen for three years as a graduate student, called his mentor a “masterful communicator,” a “man of great faith with fiery energy,” and “a real gentleman” who was always positive and helpful. Sheen could be sharply critical of positions, but not of people. Sister Ann Edward, as a graduate student at CUA, was one of many young people who would drop by to watch Sheen in action. “I joined them several times to hear and enjoy this remarkable, appealing priest. Inspiration, beauty, wit—these and other virtues, plus a melodic voice, explained why corridors around his classroom always bulged with people.[9]

Christopher Owen Lynch shares his own personal experience with Sheen in his book, Selling Catholicism, writing:

While pursuing my Ph.D. at the Catholic University of America in the mid-1940s, I audited the one graduate course Sheen’s teaching schedule called for. Every chair in the room was taken well before class time, although there might have been only six or seven students following the course for credit. It was a standard two-semester history of philosophy, from the pre-Socratics to Kant, and on through the British pragmatists and modern existentialists. The well-planned lectures were delivered flawlessly. He used the blackboard in his flowering hand to good effect, chiefly for the spellings of names or terms in Latin and Greek, French and German. He stopped exactly at the stroke of the next hour. Each class was a masterful performance of the teacher’s art.[10]

Of course, it was not necessary for Sheen to prepare as fastidiously as he did. Sheen had a superior intellect by any standard, and there was no need to have his lecture points memorized. But Sheen felt that he had a serious duty to provide his students with only the best. Sheen writes:

I felt a deep moral obligation to students; that is why I spent so many hours in preparation for each class. In an age of social justice one phase that seems neglected is the moral duty of professors to give their students a just return for their tuition. This applies not only to the method of teaching but to the content as well.[11]

Among the many intellectual virtues that teachers are encouraged to cultivate, this may be the one that Sheen realized most in his life. Sheen’s views on education—that education was sacred because of its ability to unite students with God, their final end—undoubtedly shaped his preparation habits. Should he have failed to adequately prepare, he may have been ill-equipped to lead his students to God; a sin that Sheen would have taken very seriously (see 1 Pet 3:15).

Even after officially leaving the Catholic University in 1950 to serve as national director for the Society of the Propagation of the Faith and to answer the increasing demand for his popular writing and speaking, Sheen never surrendered his habit of sustained study and extensive preparation. One would have expected that by the time Sheen was approached by the Du Mont Network to star in an experimental religious television broadcast—what would become his trademark Life Is Worth Living television show—such preparation would have been unnecessary. In typical Sheen fashion, he remained resolute in his methods.

Sheen said that he spent roughly thirty hours preparing for each television broadcast, each of which ran for just over twenty minutes in length.[12] Employing the same method of writing and rewriting his notes, Sheen memorized the points for each episode. “There was never any rehearsal for our television show,” Sheen recounts.[13] By the time he arrived at the studio the lecture was his. So effective was he on television that other religious preachers, presumably fearful of losing congregation members to Sheen, would often jest, “His Excellency should be Sheen but not heard.”[14]

Most extraordinary was Sheen’s final method of preparation in the days immediately leading up to the TV broadcast. Sheen would test out his grasp on a prepared lecture by rehearsing it entirely in Italian and in French to listeners fluent in both languages. Thinking his points out in foreign languages forced him to have total mastery over his remarks. Only if he could be comfortable and dynamic in both languages would he feel truly prepared. This is what allowed Sheen to deliver his broadcasts without the use of notes, a teleprompter, or, as he called them, “idiot cards.”[15] He tells us, “On television, I depended more on the grace of God and less on myself . . . [I wanted] the illumination that fell on any soul [to be] more of the Spirit and less of Sheen.”[16]

Sheen unreservedly embraced his teacher persona on Life Is Worth Living. He used nothing other than the skills he honed as a professor at the Catholic University of America—and the same familiar tools: chalk and his famous blackboard.[17] What he offered his viewers was rich and intellectual, academic yet accessible, serious yet humorous, calculated yet spontaneous, and, most importantly, he united it all in Christ.

Sheen was beloved by his viewers for all these reasons. Through his well-developed examples and analogies, Sheen had the ability to make his audience feel learned by bringing strange and difficult concepts down to the level of the average person. Sheen enjoyed regularly weaving in Greek poetry and drama, Aristotelian metaphysics, and Latin quotations from Thomas Aquinas when at all possible.[18] In it all, Sheen never made his audience feel inadequate—the mark of a master teacher.

Those active in the classroom today would do well to learn from the rigor of Sheen’s preparation. Sheen was an excellent instructor precisely because he left no room for mediocrity and understood that nothing—save only for grace—replaces hard work. His steps were deliberate, his lesson calculated, and he never spoke on a subject unless he truly understood it and was prepared to communicate it systematically and unpretentiously. No gimmicks were to be found among his methods. Instead, Sheen let his preparation, his understanding of the subject, his wit, and his confidence in the Divine Assistance carry him and his audience through a lecture. And, no matter the subject—philosophy, science, politics, culture, psychology, literature—Sheen found a way to bring his audience back to the most important of all themes: Christ. This, of course, was to be expected. For Sheen, everything in the final analysis was about Christ.

2. A Refusal to Grow Stagnant

Sheen tells us that after receiving his agrégé degree from Louvain in 1925 he paid a visit to the esteemed Thomistic scholar Cardinal Désiré-Joseph Mercier.[19] The young, reverential Sheen entreated the Belgian cardinal, “Your Eminence, you were always a brilliant teacher; would you kindly give me some suggestions about teaching.” Mercier responded with two charges. The first was:

Always keep current: know what the modern world is thinking about; read its poetry, its history, its literature; observe its architecture and its art; hear its music and its theater; and then plunge deeply into St. Thomas and the wisdom of the ancients and you will be able to refute its errors.

And the second:

Tear up your lecture notes at the end of each year. There is nothing that so much destroys the intellectual growth of a teacher as the keeping of notes and the repetition of the same course the following year.[20]

Sheen interiorized both these charges and made them central guideposts during his teaching career. Cardinal Mercier’s suggestions went on to form what I am identifying as a second of Sheen’s most noteworthy pedagogical practices: a refusal to grow stagnant.

Mercier’s first piece of advice to Sheen sounds today not unlike the famous counsel of Karl Barth, who suggested that the theologian proceed with the Bible in one hand and the newspaper in the other. Sheen certainty would have endorsed such wisdom. Sheen felt an intense sense of duty to the world in which he was presently living—the world needed to be approached as it was then and there, Sheen thought, with all its newfangled concerns and complexities. “We are solemnly bound by our teaching methods to prepare our young to meet the problems which their age presents,” Sheen writes. “We are responsible to the times in which we live and on judgement day, teachers will not be asked how many skeletons they exhumed from the past and re-buried in the dust, but how well they served the cause of the truth in the days of their flesh.”[21]

Sheen believed that having his finger on the pulse of the world made him all the more ready to engage it and to do so with exciting and relevant methods. For this reason, Sheen kept broad interests. Sheen said that he would read anything that he thought might “be useful for a priest in instructing or discoursing with others, or in supplying material for communication.”[22] About Sheen’s desire to always remain relevant and engaging, Reeves writes:

Sheen loved browsing in bookstores, often emerging with a dozen, perhaps twenty books. All would be quickly and thoroughly digested. (A priest who worked for Sheen later in life tested Sheen’s breakfast conversation about a book he had started to read upon retiring for the night, and found the volume thoroughly marked.) At Sheen’s funeral, a close friend said of him, “He always had to have new books, he loved meeting interesting people and informed people, the latest scientific discoveries and technological devices fascinated him.” Sheen had “an intellectual curiosity that never deserted him.”[23]

Sheen himself was never shy to discuss his love for books and for new and exciting information. Sheen writes, “Books are great friends; they always have something worthwhile to say to you when you pick them up. They never complain about being too busy and they are always at leisure to feed the mind.”[24] Sheen certainly fed his own mind.

But we must not think that Sheen was merely a bookworm. Rather, Sheen was deeply interested in what the world’s modern thinkers, political leaders, and, as we call them today, “influencers” were up to. This drove him to read extensively and with great purpose. It is also what moved him to embrace the mediums of radio and television. Sheen wanted to engage people in ways familiar to them and to use the most advanced methods possible. In her own analysis of Sheen’s success and popularity, Kathleen L. Riley writes:

Sheen learned that a preacher had to be universal in study, widely informed about the world and the interests and needs of his audience: “In talking to wise men, men must be wise.” At the same time, from a psychological viewpoint, a preacher must also “establish a common denominator with the masses.” This combination of scholarship and the common touch was the key to Sheen’s great success.[25]

Little did Mercier know that by the time he offered this first token of advice Sheen had already read every line that Thomas Aquinas ever wrote.[26] Sheen did so while working on the book to be published for his agrégé degree. This is just how Sheen operated. If he was going to study and know a thinker, then he was going to know the thinker inside and out. Later, Sheen would go on to read everything he could get his hands on regarding the philosophy of communism and the thought of Marx and Lenin. Sheen felt that serious study and continuous intellectual development was a duty if he was going to be an honest speaker and critic of communism.[27] Many of today’s popular speakers and commentators could take a lesson from Sheen here. Too many, it seems, often speak dogmatically on topics about which they are insufficiently informed. “Our country,” Sheen writes, “is suffering not so much from falsehood as from the unbearable repetition of half-truths.”[28] Half-truths, Sheen thought, are particularly insidious. They, like half-cocked guns, can fire off unsuspectingly, causing much unforeseen damage.

Sheen also heeded Mercier’s second charge—to tear up his lecture notes at the end of each year and to never teach the same course twice. Teachers today might see the wisdom in this directive but are unlikely to ever adopt such a practice. Designing an academic course is grueling work if done well, and teachers generally prefer to do it as infrequently as possible. Designing a new course requires meticulous planning and foresight, a sagely prepared reading list, carefully crafted assignments that reinforce learning, and assessments that accurately measure student progress. Rarely are all of these elements accomplished when a course is first offered. If anything, the first offering of a new course is generally a trial run that will hopefully be mastered in future installments. Sheen aimed for excellence on a course’s first run.

Sheen never did repeat the same course during his twenty-three years at the Catholic University of America.[29] Granted, the courses he taught each semester were interrelated and always driven by Sheen’s commitment to Aquinas. During his years at the Catholic University of America, Sheen taught courses entitled “Philosophy of the Christian Religion,” “Science and Religion,” “The Modern Idea of God in the Light of St. Thomas,” “God and Society,” “Philosophy of Science,” “God and Modern Philosophy,” “Natural Theology,” and “Humanism and Religion.”

Sheen was aware of the work necessary in designing strong academic courses. But this did not discourage him from embracing Mercier’s counsel; he saw it more important to avoid intellectual stagnation and to ensure his own acuity than to use his summer months for other, and potentially more profitable, work.

Sheen’s commitment to his own intellectual advancement made it possible for him to not only excel in the classroom, but also to remain a trusted and informed voice in the American Church and in broader American culture during the twentieth century. His refusal to grow stagnant, or as Sheen says, his drive “to climb [rather than] to slide,”[30] should inspire teachers and academics today to pause and consider how and by what means they are remaining academically sharp and furthering their own development. “A teacher who himself does not learn is no teacher,” Sheen claimed.[31] They are instead, Sheen once quipped, no better than “a textbook wired for sound.”[32] These educators have lost the passion that sustains all education: knowledge and love of the truth.[33] If students deserve a just return for their tuition, as Sheen suggests they do, then instructors, it seems, have a duty to regularly expand their own intellectual work, interests, and academic horizons.

3. Thinking in the Presence of the Blessed Sacrament

On the day of his ordination, Sheen made two resolutions: (1) to celebrate Mass every Saturday in honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary petitioning her protection over his priesthood and (2) to make a Holy Hour every day in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament. Sheen fulfilled both of these resolutions without fail until the day he died. These practices gave birth to the intense devotion that Sheen had to both the Blessed Virgin Mary and to the Eucharist throughout his life. So central were the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Eucharist in his life that Sheen often prayed that he would die on a Marian feast day, and in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament. Sheen died on Sunday, December 9, 1979 (one day after the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception) while in prayer before the tabernacle in his private chapel.[34]

Sheen’s daily Holy Hour was the most important part of his day. He devotes a wonderful chapter in Treasure in Clay entitled “The Hour That Makes My Day” to his reflections on sixty years of making a daily Holy Hour. There, Sheen describes with intimate language how his relationship with Christ deepened and matured as he kept this practice throughout the entirety of his priesthood. He writes:

It is impossible for me to explain how helpful the Holy Hour has been in preserving my vocation. . . . [the Holy Hour] kept my feet from wandering too far. Being tethered to a tabernacle, one’s rope for finding other pastures is not so long. That dim tabernacle lamp, however pale and faint, had some mysterious luminosity to darken the brightness of “bright lights.” The Holy Hour became like an oxygen tank to revive the breath of the Holy Spirit in the midst of the foul and fetid atmosphere of the world.[35]

Of the many benefits that came with devoting himself to significant time in prayer before the Eucharist, Sheen describes how intellectually and spiritually profitable this form of prayer was for him. Sheen claims that every good idea for a lecture, sermon, or book was born during his time in prayer before the Eucharistic Lord. There, in front of the tabernacle, Sheen thought with Christ. This is where Sheen worked out his intellectual difficulties and where his mind, he believed, could be shaped by Christ’s. This is the third and final of Sheen’s notable pedagogical methods that will be proposed here: thinking in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament.

For Sheen, there was no better place to work than before the Lord himself, present in the Blessed Sacrament. As physical proximity is important for lovers as they come to know and understand their beloved, so too, Sheen thought, is physical proximity to the Eucharist important for one who desires to know and take on the mind of Christ. Sheen writes:

I have often been asked how to prepare sermons, and I can only speak of my own experiences after a long life of preaching. All my sermons are prepared in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament. As recreation is most pleasant and profitable in the sun, so homiletic creativity is best nourished before the Eucharist. The most brilliant ideas come from meeting God face to face. The Holy Spirit which presided at the Incarnation is the best atmosphere for illumination. Pope John Paul II keeps a small desk or writing pad near him whenever he is in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament; and I have done this all my life—I am sure for the same reason he does, because a lover always works better when the Beloved is with him.[36]

Not only would Sheen work out his lectures and sermons before the tabernacle, but Sheen would also deliver his remarks to Jesus in the Eucharist. Sheen tells us:

I will then talk my thoughts to Our Lord, or at least meditate on it, almost whispering the ideas. It is amazing how quickly one discovers the value of the proposed sermon. . . . “Giving the sermon before Our Blessed Lord” is the best way for me to discover not only its weaknesses, but also its possibilities.[37]

Sheen believed that he was given real and meaningful insights from Christ in the Eucharist that he found nowhere else. This is why after a lifetime of such prayer Sheen described his Holy Hour as his personal “magister and teacher.”[38]

The intellectual luminosity received from his thinking in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament, Sheen claims, is what kept him ever afresh with ideas for books, sermons, lectures, and for his radio and TV addresses. This encouraged Sheen to construct a chapel in the central areas of both his Washington D.C. and New York City apartments. Doing so ensured that he would never work, think, and write apart from Christ’s Eucharistic presence. Sheen wrote and recorded dozens of audiotapes for converts at a desk that he had situated to face the tabernacle in his home. In Treasure in Clay he writes, “Even this autobiography is written in His presence, that He might inspire others when I am gone to make the Hour that makes Life.”[39]

In his later years, there is no topic that Sheen preached more when addressing priests and religious than the Holy Hour. He encouraged them to take up the daily Holy Hour and to begin the practice of thinking and writing in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament. In The Priest is Not His Own, Sheen writes:

The only defense against acedia, against the tragic loss of divine reality, is a daily renewal of faith in Christ. The priest who has not kept near the fires of the tabernacle can strike no sparks from the pulpit. What answer to judgement shall the priest give who squanders hours a day on newspapers, television and magazines yet cannot spare an hour of the Lord’s time to prepare his soul for the pulpit?[40]

Writing later in the same vein, Sheen entreats again:

How much more would our words burn as we preach if we prepared our sermons before the Eucharistic Lord; if our meditation each morning was on the subject of next Sunday’s sermon; if, before preaching, we prayed for five minutes to the Holy Spirit for Pentecostal fire; if we kept the Scriptures ever open near us, that we might gird ourselves with their truth when mounting the pulpit![41]

Priests, and all those entrusted with diffusing the Divine, who fail to bring their intellects before the Eucharistic Lord seem to forget, in the words of Sheen, that “theological insights are gained not only from the two covers of a treatise, but from two knees on a prie-dieu before a tabernacle.”[42]

While Sheen’s encouragement to write and think in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament was generally aimed at priests and religious, his advice seems equally fit for teachers and educators—especially those who work in the areas of theology and catechesis. All teachers and educators have experienced moments of particular opacity and confusion in writing lectures and composing lessons. Those, too, who regularly write are familiar with the kind of insipidity that can often seize one’s mind in the midst of a long, arduous project. Sheen’s practice of bringing his thoughts before the Eucharistic Lord should inspire Catholic educators to consider how much more effective their work could be if it was brought before the tabernacle in prayer, if the Lord himself was invited to be their very co-teacher and co-writer. If teaching really is, as Sheen would have it, “a prolongation of the Divine Word,” then could there be any better way to prepare than with the Divine Word himself?

Sheen’s Eucharistic prayer life animated the teaching, thinking, and writing that marked his career. It is hard to imagine how Sheen could have authored texts like The Divine Romance, The Seven Last Words, and, his masterpiece, Life of Christ without the kind of knowledge and intimacy that comes only from hours spent in prayer before Christ in the tabernacle. “Not all the Ph.D.’s are saints,” Sheen writes. “Though God can be discovered by study, instruction, and reading, these alone will not bring one to God.”[43] Our knowledge and understanding of Christ must, he says, be “preceded by a personal encounter with Him.”[44] The same is true for all those who teach and educate in Christ’s name. Their power and efficacy must be drawn from the tabernacle lest they forget that it was to Christ alone that “all power in heaven and on earth has been given” (Matt 28:18).

Conclusion

It is clear that Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen lived, as the Congregation for the Causes of Saints declared, a life of “heroic virtue” in his lifelong effort to teach and hand on the faith. The three pedagogical practices that I have raised here—his preparation methods, his refusal to grow stagnant, and his practice of thinking in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament—demonstrate Sheen’s unwavering commitment to Christ, to the Church, and to the intellectual and spiritual formation of all those entrusted to his care. It is my hope that some of what has been presented here might inspire today’s educators, evangelists, and catechists to consider how their work might be enriched were they to adopt any of the pedagogical practices of Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen.

Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, pray for us.

[1] Reeves adopted the title from a phrase in Sheen’s autobiography, Treasure in Clay:

I believe that we spend our last days very much the way that we lived. If we have lived with ease, taking our rest, never exerting ourselves, then we have a long dragging out of our days, like a slow leak. If we live intensely, I believe that somehow or other we can work up until the day God draws the line and says: “Now it is finished” (Fulton J. Sheen, Treasure in Clay [New York: Doubleday, 1982], 183).

[2] Thomas Reeves, America’s Bishop: The Life and Times of Fulton J. Sheen (San Francisco: Encounter Books, 2001), 16.

[3] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 18–20.

[4] Sheen never enjoyed the work that belonged to his family’s farm. He tells us:

Those who now me now find it hard to realize that there was once a time in my life when I plowed corn, made hay while the sun shone, broke colts to harness, curried horses, cleaned their dirty stalls, milked cows morning and night and in cold, damp weather, shucked corn, fed the pigs, dug postholes . . . . I argued with my father every day that farming was not a good life and that you could make a fortune on it only if you struck oil (Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 18).

[5] Francis Sugrue, “The Bishop Sheen Story: Philosopher, Theologian, Administrator, ‘Beggar,’” The New York Herald Tribune, March 2, 1959.

[6] Fulton J. Sheen, Victory Over Vice (Garden City: Sophia Press, 2004), 90; see also Thomas Reeves, who uses this quotation in describing Sheen’s philosophy of work (America’s Bishop: The Life and Times of Fulton J. Sheen, 339).

[7] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 52.

[8] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 55–56.

[9] Reeves, America’s Bishop: The Life and Times of Fulton J. Sheen, 77–78.

[10] Christopher Owen Lynch, Selling Catholicism (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1998), viii.

[11] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 54.

[12] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 70.

[13] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 68.

[14] James C. G. Conniff, “The Bishop Sheen Story” (New York: Fawcett Publications, 1953), 2.

[15] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 68.

[16] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 73.

[17] Sheen believed that his years at the Catholic University of America prepared him especially for the success he experienced on Life is Worth Living. In fact, Sheen thought of his television program as an extension of his work in the classroom rather than as a religious program aimed at preaching or, worse, proselytizing. In her biography on Sheen, Kathleen L. Riley, quoting a 1953 interview with Sheen, writes, “In Sheen’s own words, his program was not preaching, but teaching: ‘You preach to those who already share your convictions, you teach those who do not. . . . my talks are meant to bring enlightenment’” (Kathleen L. Riley, Fulton J. Sheen: An American Catholic Response to the Twentieth Century [Staten Island: Alba House, 2004], 222).

[18] While some might claim that Sheen would do this as a vain attempt to showcase his own intellectual prowess, I think it is more likely that this was simply how Sheen’s mind operated. Sheen knew Greek, German, Italian, Latin, and French. People who knew him often said that he “thought in Latin,” which he really did (Reeves, America’s Bishop: The Life and Times of Fulton J. Sheen, 3). All of Sheen’s courses at Louvain were in French and Latin. A large number of his personal notebooks from his courses during these years, which are held in the archives at CUA, are entirely in French and Latin.

[19] Mercier (1851–1926) was the voice of neo-Thomism in the late ninetieth and early twentieth century; he served as chair of Thomism at Louvain from 1882–1905 and, responding to Leo XIII’s call for a revival in scholastic philosophy in his encyclical Aeterni Patris (1897), established the Higher Institute of Philosophy at Louvain in 1899, causing Louvain to emerge as the epicenter for the Thomistic revival of the early twentieth century.

[20] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 51.

[21] Fulton Sheen, “Educating for a Catholic Renaissance,” reprinted in the National Catholic Educational Association Bulletin XXVI (November 1929), 53–54. Riley includes an abbreviated version of this same quotation in her biography on Sheen in the section treating Sheen’s efforts to revitalize Catholic education in the twentieth century. See Kathleen L. Riley, Fulton J. Sheen: An American Catholic Response to the Twentieth Century (Staten Island: Alba House, 2004), 20–23.

[22] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 78.

[23] Reeves, America’s Bishop: The Life and Times of Fulton J. Sheen, 77.

[24] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 76.

[25] Riley, Fulton J. Sheen: An American Catholic Response to the Twentieth Century, 72.

[26] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 27.

[27] Riley, Fulton J. Sheen: An American Catholic Response to the Twentieth Century, 131.

[28] Fulton J. Sheen, Old Errors and New Labels (New York: Alba House, 2007), 177.

[29] The records at the Catholic University of America indicate that Sheen did teach courses of the same or a similar title on a number of occasions. In his autobiography, Sheen admits that his courses were often very similar. To this end, Riley notes:

During the late thirties and forties, when it was estimated that Sheen filled over “150 speaking dates a year,” he had the tendency to fall back on the same courses, offered in alternate years, and a seminar in Natural Theology (Riley, Fulton J. Sheen: An American Catholic Response to the Twentieth Century, 19).

[30] Fulton J. Sheen, The Priest Is Not His Own (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2004), 132.

[31] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 54.

[32] Sheen, Life is Worth Living, “How to Improve Your Mind.”

[33] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 55.

[34] Riley, Fulton J. Sheen: An American Catholic Response to the Twentieth Century, 312–313. This, curiously, is the date when many Eastern Christians celebrate Mary’s conception. Sheen was bi-ritual and was known for celebrating the Byzantine Divine Liturgy as a way of remaining spiritually close to persecuted Eastern Christians.

[35] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 191–192.

[36] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 75.

[37] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 76.

[38] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 198.

[39] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 198.

[40] Sheen, The Priest Is Not His Own, 133

[41] Sheen, The Priest Is Not His Own, 134.

[42] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 194.

[43] Fulton J. Sheen, Lift Up Your Heart (Liguori: Liguori Publications, 1997), 139–140.

[44] Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 190.