ROME — On the Sunday before Easter, the priest’s phone rang.

The Rev. Claudio Del Monte carried the phone, given to him by staff in the Bergamo hospital, along with a small cross and some homemade sanitizer. Instead of his usual cleric’s collar, he wore disposable scrubs, a surgical mask covered with another mask, protective eyewear and a cap over his head. On his chest he had drawn a black cross with a felt pen.

He excused himself from two coronavirus patients he was visiting in the hospital and answered the call. But he already knew what it meant. Minutes later, he arrived at the bedside of an older man he had met days earlier. An oxygen mask now obscured the man’s face, and intensive care staff huddled around his bed.

“I blessed him and absolved him from sins, he squeezed my hand tightly and I stayed there with him until his eyes closed,” Father Del Monte, 53, said. “And then I said the prayer for the dead, and then I changed my gloves and continued my round.”

Italy’s coronavirus outbreak is one of the world’s deadliest, and while the doctors and nurses on the northern Italian front line have become symbols of sacrifice against an invisible enemy, priests and nuns have also joined the fight. Especially in deeply infected areas like Bergamo, they are risking, and sometimes giving, their lives to attend to the spiritual needs of the often older and devout Italians hardest hit by the virus.

Across Italy, the virus has killed more than 100 priests, many of them retired and especially vulnerable to a scourge that preys on older people, whether it be in nursing homes or monasteries. Avvenire, the newspaper run by the Italian bishops conference, is honoring the dead with the hashtag “PriestsForever.”

But some priests have also fallen in service, and in a Holy Thursday Mass in an empty St. Peter’s Basilica, Pope Francis remembered them.

“In these days, more than 60 have died here in Italy, attending to the sick in the hospitals,” he said, calling them “the saints next door, priests who gave their lives in service.”

Francesco Beschi, the bishop of Bergamo, said he had lost 24 priests in 20 days, in a region where more than 2,600 people have died of the virus by the official count. About half the priests were retired and out of service, but others still tended to pastoral duties.

They offer solace through WhatsApp groups, wave from behind car windows as they bring food to the sick, lean against the door frames of infected bedrooms as they deliver last rites and shroud themselves in personal protective equipment as they whisper prayers and encouragement at hospital bed sides.

They complain they cannot get closer, that the last touch the faithful feel is a gloved one, that the last face they see is often on a screen. With a virus that separates families and spouses as it kills, priests said that they were also pained to be distanced from their flock when they were needed most.

One of those was the Rev. Fausto Resmini, 67, esteemed as the chaplain of Bergamo’s prison for nearly 30 years and the founder of a center for troubled youth. His fellow priests said that in the course of his work last month, he caught the virus. He received treatment at the Humanitas Gavazzeni hospital where Father Del Monte does his rounds, before dying on March 23.

Local residents are trying to name a new field hospital after him.

“His death is a huge loss for the Bergamo church,” said the Rev. Roberto Trussardi, director of Bergamo Caritas, the church’s charitable arm.

Such sacrifices have not deterred many other priests from ministering to the sick.

“Staying home is the right thing to do,” said the Rev. Giovanni Paolini, 85, in the central Italian town of Pesaro. “But I am a priest and sometimes it is necessary to bend the law to meet people’s needs.”

On Monday, he said a burial prayer for one of the 15 members of a local parish killed by the virus.

He said he used the phone or social media when possible to console. But he also said he puts on his mask and other protective gear to visit old people fearing death, often alone.

“You choose this life to be useful to others,” he said.

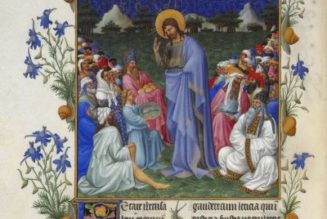

Those priests embody a vision of the church articulated by Pope Francis, who has often invoked the image of a field hospital and the characters of the Italian masterpiece, “The Betrothed,” in which heroic Milanese priests selflessly treat those afflicted by the plague.

On March 10, Francis prayed in a morning Mass, “for our priests, so that they have the courage to go out, and go to those who are sick.”

That encouragement seemed in violation of restrictions Italy adopted that very day that sought to keep people in their homes to prevent the spread of the virus, but the Vatican’s spokesman immediately argued that the pope’s appeal clearly understood the need for priests to act “while respecting the health measures established by Italian authorities.”

Cardinal Michael Czerny, a close adviser to Francis, said that the pontiff has seemed calm but also intensely involved in the church’s response to the virus in recent days.

“What makes him most happy are the priests who don’t need to be told, but who know that this is what they should do,” he said. “If he had his druthers, he would be on the front lines, too.”

“He wants us at the frontiers,” Cardinal Czerny said. “And beyond the limits.”

Those limits are not safely placed. And once the danger of contagion became clear, Bishop Beschi said, priests began adopting the appropriate precautions. He had sent a letter to his own priests telling them, “We want to bring Christ to people but not contagion.” He added, “This was a painful choice, because it was a limitation.”

In Castiglione d’Adda, one of the first towns quarantined by the Italian government during the initial February outbreak, nearly all public religious ceremonies and services have ceased. The Rev. Gabriele Bernardelli, 58, said he kept contact with his parishioners through WhatsApp and Instagram. The phone, he said, “becomes a pastoral instrument.”

But he said that the vast majority of the 67 people his town lost in the last 40 days had died in the hospital, and that he had not been able to see them. He took some solace in the fact that local bishops had deputized devout medical workers in hospitals to make the sign of the cross on a dying patient’s forehead.

Last month, during the explosion of cases, Father Bernardelli visited the home of an older man, the father of a priest, as he lay dying in his bedroom.

“I used to be close to a dying person, like a doctor next to the sick,” he said. This time he stayed at the threshold of the door watching the man clutch a tank of oxygen. Father Bernardelli delivered last rites through a mask from outside the door frame.

“This is what you can do,” he said.

Father Del Monte also visits the sick at home. A chemist by training, he has made vats of disinfectant. He dabs it in his nostrils and rubs it on his hands.

The precautions were both to protect himself and to make sure that he did not inadvertently spread the virus himself, as he goes home to home.

“Like all my priest friends, we go around to the houses,’’ he said, ‘‘so we cannot be the ones who bring the contagion. We cannot only get the sickness, we can give it. Maybe we are asymptomatic, and then it’s a disaster.”

Last week, he too delivered last rites in a mask from the threshold of a bedroom, this time for a woman in his parish. He added that on Monday morning, he said simple prayers at the Bergamo cemetery during a burial.

“Three or four minutes,” he said.

Before 3 every afternoon, he leaves his parish, changes out of his clerical clothing and gets dressed for visits in the hospital, which falls within his parish.

He has comforted wives whose husbands died in other hospitals and lingered when doctors rushed off.

“The priest’s time is freer,” he said, adding, “It’s not about looking for it, it’s about accepting the suffering that comes.”

Sometimes he sees new patients taking the place of the dead he prayed with the day before. But he has also found a letter on the bed of a patient who survived.

“Until next time,” it read.