When a Catholic parish closes, its diocese saves the contents that might be of future use: crucifixes, candelabras, or pictures of the pope. The pieces are excised and brought to a warehouse where they are stored as “Church Patrimony.” In the Brooklyn Diocese’s East New York warehouse sits one long-forgotten piece of patrimony, a strange relic for a Christian god and another similarly fickle master: New York City transit.

It’s the unique altar used at St. Michael-St. Edward Church in Fort Greene, made from the leftover steel of the decommissioned Myrtle Avenue El and used at mass for 38 years until the church was closed in 2010.

The altar’s story begins with the end of the elevated train system in New York City. The “Els” were privately operated, aboveground lines that cropped up in the second half of the nineteenth century. I happen to be a third-generation, oft-stranded resident of central Queens with a lifelong soft spot for trains. My grandmother rode the El a few times; my dad remembers it faintly.

Built in 1888, the Myrtle Avenue El ran from the Brooklyn side of the Brooklyn Bridge to Metropolitan Avenue in Queens.

As the municipally operated subterranean system expanded, the slow and noisy old Els struggled to keep up. Manhattan’s Els were gone by 1955, and outer-borough lines soon met similar fates.

In 1944, train service over the Brooklyn Bridge ended, eliminating the Myrtle El’s Manhattan-bound connections and rendering the train, in the words of Peter Dougherty, author of “Tracks of the New York City Subway,” an “El to nowhere.”

Then the factories and shipyards that employed the Myrtle El’s ridership disappeared, and the El became a symbol of and scapegoat for this decline.

In a 1965 interview with the Williamsburg News, soon-to-be City Councilman George Swetnick called the line a “dilapidated, cancerous blight,” and declared that “the community knows it will experience a rebirth once the ‘El’ comes tumbling down.”

Four years later, at 11:30 p.m. on October 3, 1969, the El made one last trip down Myrtle Avenue. The next day, riders swapped the old wooden train cars—the last in service anywhere in America—for a shiny new metal bus, the B54.

But one woman thought there was something of the El worth saving. In her day job, Carol Dykeman worked as the arts education coordinator for the Brooklyn Diocese’s elementary schools. She also happened to be a Pratt Institute-trained welder. The Myrtle El’s viaduct was made of steel, and its Navy Street station in Fort Greene happened to be around the corner from the historic Saint Michael-St. Edward’s Church, which was built in 1906.

Dykeman had an idea. In 1970, while City workers demolished the line, she asked if they could save a piece of it for her. The MTA approved the request and soon delivered her a half-ton of metal. The following summer, Dykeman set up shop in an empty lot in Fort Greene near St. Michael-St. Edward’s and got to work cutting, sanding, stripping paint, and welding, turning the discarded metal into something beautiful—and something holy.

Dykeman made an altar. She inverted and spliced together the corners of two arches, with the adjoined support beams reaching upwards to hold a tabletop. The metal alone weighed some nine hundred pounds. It took a makeshift crane and a gaggle of church boys to move it.

“Everybody was willing to lend a hand,” recalled Robert Zakarian, a longtime professor of sculpture at Pratt who designed the altar’s 600-pound maple butcher block top. Zakarian, who taught woodworking at Pratt from 1961 to 2021, took on the project pro bono. “I thought it was nice. A good thing, not a bad thing,” said Zakarian, now 84. “Schmaltzy, but not bad.”

The altar debuted to fanfare at St. Michael’s, with the February 13, 1972, dedication earning a write-up in the Brooklyn section of the Daily News.

“The demolition crew thought it was hysterically funny when I would go down and say, ‘Will you save me four feet of that pillar?’” Dykeman told the News. And despite the heat, heft, and unsolicited advice she received from passersby, welding together the behemoth proved “a lot of fun.”

“An eyesore is now a thing of beauty,” remarked the church’s beloved Reverend Anthony J. Failla.

Failla and two other parish priests were later accused of abusing boys in the St. Michael-St. Edward rectory during the 1970s—an act Failla reportedly admitted to his superior and denied to the public. Failla was removed from the ministry and disappeared to Florida, where he was spotted performing mass in 2002. He was again banished and died in 2018.

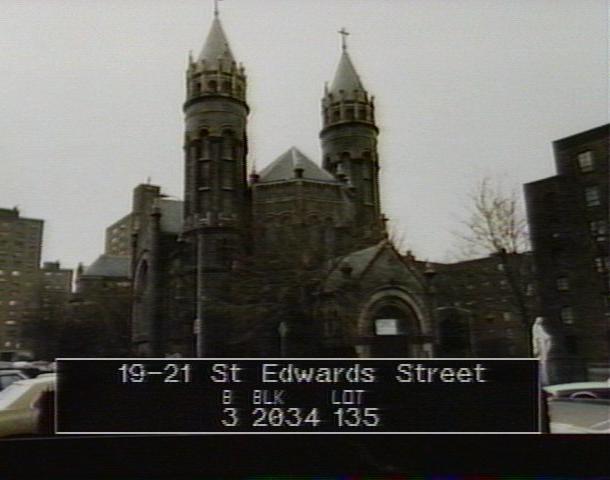

Mass at St. Michael-St. Edward was celebrated with the old El altar until 2010, when the diocese shuttered the church. It has since sat vacant, and this March, the Diocese filed for demolition permits. One hundred and five apartments will take the church’s place.

The only public remains of the Myrtle El are the abandoned upper level of the Myrtle-Broadway station, where the M train joins the J and Z down Broadway, and the metal ribs that still jut out one block from that station down Myrtle Avenue.

Records of Carol Dykeman’s life are scant. It appears that Dykeman was born in Brooklyn in 1937 to parents John and Myrtle (yes, Myrtle), and that she died in 2013.

Today, the altar sits in the East New York warehouse of the Office of Patrimony, and it’s no longer whole. In order for the piece to be evacuated from St. Michael-St. Edwards, the metal had to be examined, measured, and then cut in half.

Zakarian retired last August. Earlier this summer, I found him at his home in Downtown Brooklyn. We talked for an hour and afterwards, I walked the mile to St. Edward’s Street and the old church. Before I left, Zakarian, who hadn’t thought about the piece in years, asked me to give him a call if I actually saw it. “It’s appropriate,” he said of my odyssey. “We shouldn’t let things just disappear.”

When I got to St. Michael-St. Edward, it was hot, and the sky threatened rain. Garbage was strewn all around. I couldn’t see in, so I went home. I took the B54 to the M. Once upon a time, the Myrtle Avenue El would have taken me door-to-door.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity