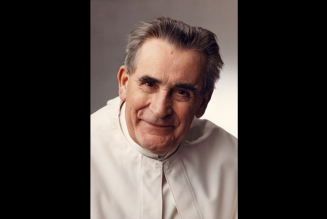

The ongoing standoff between the Bishop Michael Olson of Fort Worth and a local Carmelite monastery of nuns took another surreal turn this week, with allegations of drug use and criminal activity flying between the diocesan chancery and the convent.

As the situation continues to get more outlandish, what do we actually know so far — and are we any closer to understanding what is going on in Texas?

What’s new

The latest developments came Wednesday, with the nuns’ lawyer, Matthew Bobo, saying they had lodged a criminal complaint against Olson’s interventions at the monastery, and police interviewed Mother Teresa Agnes Gerlach of Jesus Crucified on June 6 in relation to phones and computers taken by the bishop’s team from the convent in the course of his canonical investigation, alleging, effectively, that Olson had stolen the nuns’ property.

Arlington police have confirmed the criminal complaint, telling the Fort Worth Star-Telegram that “The department has launched an investigation to determine whether any criminal offenses have occurred, which is standard anytime a criminal complaint is made.”

The lawyer’s statement triggered a furious reaction from the Fort Worth diocese, which issued a statement denouncing the nuns’ civil legal counsel for “another transparent attempt to spread baseless and outrageous accusations regarding Bishop Olson’s legitimate investigation,” which they called an “attempt to embarrass Bishop Olson and undermine his authority.”

The diocese went further, saying Wednesday that it had “initiated and is in communication with the Arlington Police Department regarding serious concerns it has regarding the use of marijuana and edibles at the monastery,” along with what it called “other issues that the diocese will address at another time and in a proper forum.”

Attached to the diocese’s statement to press were what it said are photos “provided by a confidential informant within the monastery” which “speak for [themselves] and [raise] serious questions that the Bishop is tirelessly working to address with law enforcement and in private.”

The images appear to show an office within the monastery with several tables strewn with drug paraphernalia, dispensary bottles, branded marijuana products, bongs, and a crucifix.

What’s already happened

Bishop Olson has been locked in a conflict with the nuns of the Carmelite Monastery of the Most Holy Trinity for more than a month, after initiating a canonical investigation into their abbess, Mother Teresa Agnes for alleged (and the diocese says admitted) sins against her vow of chastity which she is supposed to have committed with an unnamed priest.

The lawyer for the nuns has previously raised questions about the mother superior’s supposed admission to some kind of sexual relationship or encounter with the priest, which she is meant to have made to the diocesan vicar general in December last year.

According to the lawyer, and to many close to the nuns, Mother Teresa Agnes was recovering from serious surgery at the time, heavily medicated, and in and out of lucidity, making anything she might have “admitted” to suspect.

They also point out that the 43-year-old superior is wheelchair bound because of her health issues and uses a feeding tube, seeming to make her an unlikely candidate for carrying on a liaison from within the cloister.

Questions have also been raised about the canonical grounds for Olson’s intervention in the matter, and the nuns have filed a million-dollar civil suit against the bishop, alongside claims that a search of the convent by the bishop and his team, including the seizure of computer and phone equipment, was financially motivated.

The diocese, for its part, has repeatedly stated that Olson is acting within the bounds of canon law, and that there are serious issues at the monastery which required his urgent intervention — including his initial move to coercively restrict the nuns’ access to the sacraments, and order the summary dismissal of Mother Teresa Agnes from the order.

The nuns have filed several canonical appeals in Rome.

While neither Olson nor the diocese had previously offered details about the supposedly wider issues at play in the convent, dramatic — and remarkably rapid — interventions by the Vatican’s Dicastery for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life have granted the bishop sweeping powers to deal with the Carmel.

What the sides are saying

The nuns, despite being in cloister, have a number of people speaking to press on their behalf, including both their civil and canonical legal representation — but even on this, the issue is complicated.

In addition to their civil attorney representing the whole monastery, Bobo, whom the diocese has accused of attempting to stoke indignation against and opposition to Bishop Olson, Mother Teresa Agnes also has a canonist, Michael J Podhajsky, appointed by Olson to represent her, after he refused to accept her own selected canonical counsel.

In a statement sent to several media outlets on June 5, Podhajsky, who was representing Mother Teresa Agnes, whom Olson has now dismissed from the order, said that “in good conscience” he could say he’d served her interests professionally and objectively and that “the ultimate decision rendered by Bishop Olson according to the canonical authority he had in leading the process, should in no way reflect upon the quality of the work I performed in the best interests of Reverend Mother.”

The canon lawyer also confirmed that, following Olson’s decree of dismissal, he was no longer involved in the case and distanced himself from both sides.

The Pillar has reported Mother Teresa Agnes and the other nuns of the monastery have retained other canonical representation to file appeals against Olson’s actions at the Vatican.

The diocese, for its part, has repeatedly denounced the nuns and their civil attorney for publicizing details of the case, and insisted that “this is an internal matter and should not be played out in the press,” and for making what it calls outlandish accusations, including that the investigation into Mother Teresa Agnes was a pretext to seize the community’s donor list.

But the Fort Worth diocese’s asserted belief that the case of the convent shouldn’t be publicly litigated hasn’t prevented it from putting out a rolling series of statements reiterating both Olson’s authority to act and the legitimacy of his canonical actions — including releasing the decree from Rome confirming his intervention.

Those statements, including the decree from Rome, have served to raise more questions than they answer about the case, the bishop’s actions, Rome’s response, and the wider context of the whole affair — none of which the diocese has answered.

What we know we don’t know

Despite the now near-daily updates coming from both sides of the case, there is a lot of information which is still not publicly known.

The supposed canonical basis for Bishop Olson’s interventions so far remains the alleged admission of some kind of sexual relationship with a priest by Mother Teresa Agnes. But the nature of that relationship is not clear, nor when it is meant to have happened, nor why investigating it would require the seizure of a phone, iPad, and a computer from the monastery.

Also unknown is the identity and status of the priest supposedly involved. So far, the Fort Worth diocese has only said that the priest is from another diocese and therefore out of Bishop Olson’s jurisdiction.

But even if the nun has admitted to some sin against the sixth commandment with a priest, it remains unclear (and unexplained) on what grounds that could be considered a canonical crime of the kind asserted by the bishop, rather than a sin which requires some other, even urgent, pastoral investigation and address.

And if the relationship was canonically criminal, as the diocese asserts, Olson’s legal mandate as bishop extends by law to all crimes committed within his territory, regardless of the diocese of incardination or residence of a priest who participates in them.

If there is, as the photos apparently showing considerable amounts of drugs and related paraphernalia at the monastery would suggest, a serious underlying issue of irreligious behavior among the nuns, the diocese has chosen an odd means and timing for making it public.

Implying, as the diocese appears to be, that the Carmelite convent has become some kind of baked out college sorority house, seems calculated to increase the kind of frenzied media speculation about the case which the Fort Worth chancery continues to insist is inappropriate and unhelpful. So why do it?

The images from within the convent, appearing to show what most people would consider to be a near industrial quantity of marijuana products, might serve to underline Olson’s insistence that there is much more to the case than meets the eye, and even to defuse some of the mounting criticism of the bishop personally.

But, as with the diocese’s publication of a decree from Rome (which misnamed the monastery and contained a three-year old protocol number), the Fort Worth chancery has developed a pattern of showing the public just enough information to further inflame curiosity about the case but without telling any of the necessary context to defuse speculation.

This pattern, together with the nuns’ increasingly acrimonious legal actions against the diocese, have successfully turned a confrontation between a local bishop and a small convent into an event of national interest for the Church in the United States.

A Roman problem, too

It remains unclear what the status is of the nuns’ current canonical appeals in Rome, both against Mother Teresa Agnes’ dismissal from the order and against Olson’s ongoing involvement with the Carmel.

It is impossible to predict if these actions will become mired in months or even years of legal wrangling before the Apostolic Signatura, or if they will be dismissed (along with Mother Teresa Agnes) with the same alacrity which the dicastery for religious orders showed in confirming Olson’s authority — managing to get a decree signed, sealed, delivered, and publicly released in a single day.

But, at this point, the case of the Arlington nuns is becoming a headache for Rome, too.

Olson has faced a torrent of criticism online for his actions — with many commentators adopting a somewhat simplistic narrative of an overweening bishop bullying a convent of cloistered nuns under a spurious pretext.

While the bishop’s chancery is making some efforts to unspin that narrative (even while raising more questions in the process), the Vatican is now facing its own criticism over the case.

The speed and resolution with which DICLSAL has appeared to act in support of Olson has been unfavorably compared to cases like that of the disgraced Jesuit artist, Fr. Marko Rupnik, who has remained a cleric, despite a litany of complaints of serious sexual abuses, as well as a brief excommunication for major canonical crimes committed against the sacrament of confession.

It is possible that further details will eventually emerge about the case which exonerate Olson’s motives for acting against the monastery, even if not the canonical rationale he has deployed.

But even if they do, many Catholics in the U.S. and further afield will be left wondering why Rome is able to marshal itself so quickly and completely when faced with a convent of nuns, but not against famous clerics, even when they are accused of blasphemous sexual crimes of abuse.

Comments 45

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews