During the advent of my first pregnancy, in 2012, I was comfortably settled into my own unique brand of postmodern feminist Christianity. I remember lounging on the couch amidst waves of debilitating nausea, watching news coverage of the controversial Contraceptive Mandate, rolling my eyes in anger and disgust at those regressive Catholic priests in their prim white collars, telling women what to do with their bodies.

Yet almost exactly two years later, I would be standing before such a priest at the Easter Vigil Mass, publicly confessing my desire to be received into the largest, oldest male-helmed institution in the world, the Roman Catholic Church. My sudden swerve into Catholicism prompted a dramatic worldview inversion on a number of issues related to feminism and sexuality, including the central feminist tenet that abortion is good for women. I can trace my paradigm shift on abortion to two underlying recognitions that dawned slowly during those two short years: a recognition of unborn personhood, and a recognition that the feminist ideal of autonomy sets a woman at war with her own body.

The First Recognition

His coming was a cataclysm: Julian, my firstborn. Something I both knew would happen and could never have anticipated.

Even before he came, when his toothpick bones were welding together in my womb, he began to change me. Especially with that second ultrasound, a sustained peek inside his world within me. The first early ultrasound had found a cyst on our umbilical cord, which could indicate a congenital abnormality, so we went in for another ultrasound to see how he was doing.

We were only twelve weeks in, just ten weeks after conception. The last time I had seen him on that murky gray screen, he had been only a lima bean huddled inside a life-giving bubble, his heartbeat a tiny window that opened and opened and opened. He was a baby then, a miniscule human, but I had to stretch my imagination to see it. Here we were, just a few weeks later; I assumed he would be a bean still, only bigger.

But no! He was still small enough that we could see his whole body at once on the screen. He was huddled no longer, but kicking and bucking around, the bubble of my womb his playpen. His head was round and perfect, his brain bloomed like cauliflower as he sucked his thumb and paddled his legs. I was shocked at how quickly he had become recognizably, indisputably human. Still within the first trimester.

His brain in full bloom. His limbs on parade, waving and churning in his amniotic ocean. His heart with its syncopated chambers, an undeniable herald: I’m alive, I’m alive, I’m alive.

In that moment, catching a glimpse of the carnival inside my womb, I began to feel unsure about what I thought I knew. Though I had never been entirely comfortable with the idea of abortion, the first trimester had always seemed like an ambiguous safe zone to me. Later on, yes, it is pretty hard to argue that the unborn fetus is not a human being—but that first third of the pregnancy, that was before the baby was really a baby, right?

Seeing this declaration of humanity on the ultrasound screen only ten weeks after we lit the spark of his existence—this undeniable reality began to erode what I thought I knew.

The erosion intensified the following June, when I was months into new motherhood. Wendy Davis, a state senator from Texas, was making headlines during her eleven-hour filibuster on the senate floor that blocked a controversial abortion bill. I remember sitting on my couch, watching the news coverage, feeling inspired. Twitter was exploding with adulation, feminists raising a battle cry in support of Davis and her pink sneakers, and I was caught up in the excitement, watching a woman make history in her defense of other women.

Tweets started flying from women who had abortions, proclaiming their choice proudly as a way of support. In the midst of the fray, a fellow writer I knew tweeted her chagrin at never having had an abortion, which prevented her from fully joining in the revelry. I read this tweet, just a string of offhand characters quickly lost in the flurry, and my enthusiasm chilled over. I had been pro-choice for years, like any good feminist, but this lauding of abortion as some kind of jubilant rite of passage, a cause for celebration, was a sentiment that stopped me cold. My unborn son at twelve weeks, a thriving tiny human on parade—this image rushed into my mind, a courier bearing a message I did not want to hear, but could no longer ignore.

Every dehumanizing ideology succumbs to the same temptation: to see the undesirable other as a non-person, and thus disposable. In this distorted light, the disposal of the unwanted person becomes not only morally permissible, but meritorious, a praiseworthy act. I have come to recognize that there is never a safe way to draw a dividing line between “human being” and “person.” That line, even when drawn with the best of intentions and the loftiest ideals, leads to gravest evil.

The Second Recognition

Before becoming a mother, in an effort to make sense of myself, to find my place in the world, I had embraced the mantle of feminism and its cardinal virtues: autonomy, self-sufficiency, equality, empowerment. These named and shaped my experience, my sense of identity. Motherhood and pregnancy had long dazzled and entranced me—but only as romanticized metaphors for a kind of selfhood that is compassionate, creative, welcoming of the other. I loved reading and theorizing and writing about these metaphors. The reality was more terrifying.

I’d watched friends and acquaintances become mothers and get swallowed into a child-centered world, where conversations about spit up and breastfeeding and birth plans reigned, where once-clean houses were overrun with laundry and plastic toys, where time was both frenzied and monotonous, where no one had sex anymore, where wives and husbands became Moms and Dads and got a bit fat. I thought of this world as Mommyland, and the inhabitants as women who lost themselves in their children and their home lives, compromising their independence and ambition and freedom, ceding control of both body and mind. I wanted to be a mother—one day, I said—but I did not want to disappear.

So I would not, I resolved. It would be different with me. I prided myself that my marriage was not like that, no fusion of identities, no joint Facebook profile. I kept my own last name, our marriage an alliance of love between two autonomous beings. Like most, my twenties were a time of intense self-discovery, and aptly so. My sense of self so newly discovered, I was afraid to lose it.

While this is hard to admit, my feminism was, in good part, self-centric. It was very much concerned with my identity, my power and potential. Of course, this expanded to include an interest in womankind more generally, but my passion for feminism nonetheless sprang from an exaltation of my own experience. I extolled the ideals of autonomy and independence—until those ideals were utterly undone by the realities of pregnancy and motherhood, the reality of Julian.

Suddenly, I was confronted with the intractability of maleness and femaleness. As it turns out, these are not mere social constructs. My femaleness is not something I chose, not something I control. Motherhood and fatherhood are not interchangeable. I grew my son inside my body. At the appointed time—unknown and undecided by us—my body birthed him, with strength I did not know I possessed. My body bled for weeks while it healed the rupture of our union. My body made sweet milk for him. I spent hours marooned in the rocking chair, sometimes enraptured, sometimes bored out of my mind, feeding him from myself. My husband, was there, too, caring for him in his way, but our experiences were not, cannot, be interchanged. Before parenthood, our domestic division of labor was equitable, fluid—but now we were at the mercy of biological realities beyond our control.

The traditional feminist solution to the “problem” of female biology is unfettered access to contraception and abortion: this reveals an ironically masculine bias. Rather than seeking to change social structures to accommodate the realities of female biology, the feminist movement, since its second wave, has continually and firmly fought instead for women to alter their biology, often through violence, so that it functions more like a man’s. Tellingly, the legal right for a woman to kill a child in her womb was won before the legal right for a woman not to be fired for being pregnant. The message is clear: women must become like men to be free.

In the “sex-positive” realm of popular feminism, where I once sought refuge, pleasure is the ruling paradigm. I was reminded of this recently, when I attended a feminist panel on sex and theology at the national convention for the American Academy of Religion. In the entire ninety minutes of discussion, with multiple female scholars presenting and an audience of female academics actively engaging, not once did anyone mention that fact that sex can result in pregnancy. It was as if we were operating within a world where that no longer happens, where new human beings emerge out of cabbage patches, or spring from men’s thighs, like Dionysus from Zeus.

Unfortunately, it is women who pay the price when this fantasy skids into reality. I remember seeing a heart-wrenching Facebook post in the midst of my conversion, in which a woman I do not personally know was explaining her decision to have an abortion. She begins the post by revealing that this is the second time she has gotten pregnant on long-term hormonal birth control, and she concludes by making a pitch for access to abortion, because “bodily autonomy exists and it exists for a reason.” There is a basic logical problem if we cannot see the contradiction there: the very fact that she is in such a difficult and painful situation is because, in fact, bodily autonomy does not exist for women as it does for men. When an unwanted pregnancy resulting from consensual sex is labeled “forced motherhood,” the question arises: who is doing the forcing? It is not the man, or society; it is the woman’s own body. This is a framework that makes women at war with themselves. Men can have sex until their eyes pop out; they will never get pregnant. This is not true for women—just ask my husband, who was conceived after a tubal ligation. The myth of complete sexual freedom, complete autonomy, is based on male biology, and women can only pursue that ideal by doing violence to themselves. Feminists, of all people, should be attuned to this, but they believe and propagate the myth as much as anyone. As I once did, wholeheartedly.

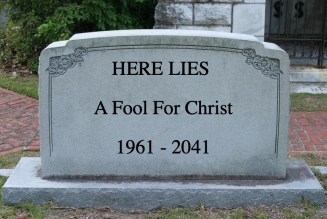

Becoming a Catholic did not make me pro-life; becoming a mother did. Motherhood unmasked the illusion of my own autonomy. The illusion that an unborn human being is not a human being. The illusion that maleness and femaleness are incidental to human existence, rather than a powerful and purposeful reality that tethers us to the created order. Catholicism, which swept in soon after I became a mother, provided me with words to name these recognitions—and, more importantly, permission to accept them, even though it meant transgressing, and ultimately abandoning, this central dogma of feminist orthodoxy.

Editorial Note: Abigail Favale is a Life and Dignity Writing Fellow with the Notre Dame Office of Human Dignity & Life Initiatives. Life and Dignity Writing Fellows are leading experts who contribute regularly to Church Life Journal on pro-life and human dignity issues. Portions of this essay have been adapted from the author’s memoir, Into the Deep: An Unlikely Catholic Conversion, available now from Cascade Books.