Editor’s Note: This story has been updated.

LANDER, Wyoming — The $10-million donation from an anonymous donor was the largest gift in the history of Wyoming Catholic College, and school leaders looked forward to using the funds to expand facilities at the campus in downtown Lander, located in the central part of the state.

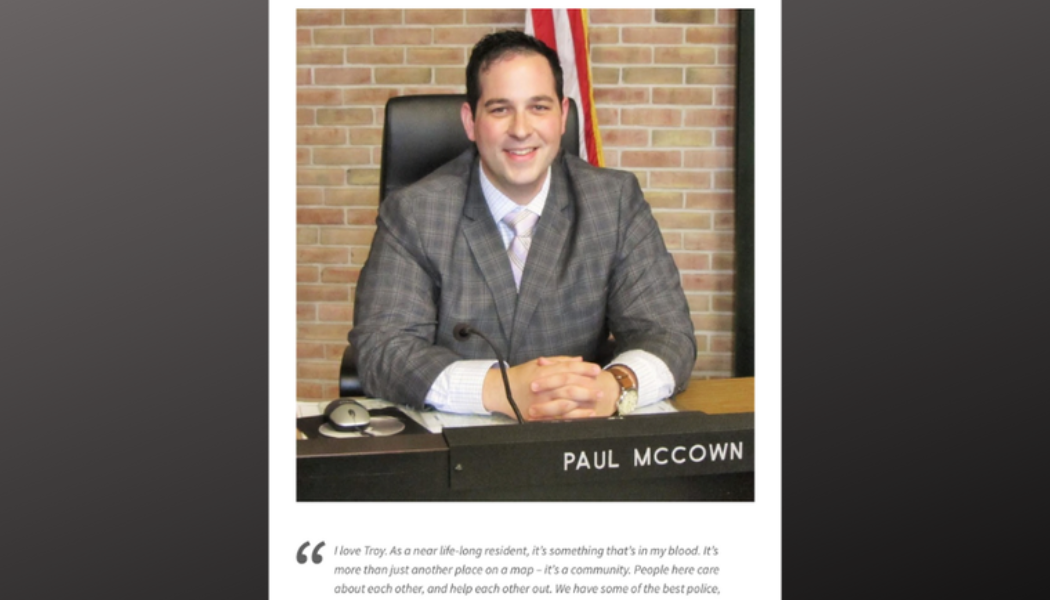

But as architectural plans were completed, with the goal of starting construction by summer’s end, Wyoming Catholic College president Glenn Arbery learned that the school’s CFO, Paul McCown, faced allegations of fraud, and the claim raised questions about the origins and legality of the large donation that had stirred such hopes.

On July 7, the college posted a statement addressing the full consequences of information brought to light in a June 22 lawsuit filed against McCown in the U.S. District Court for the District of Wyoming.

“McCown — without the knowledge of the college — fraudulently obtained a substantial amount of money through alleged illicit transactions,” read the statement.

“Some of those funds were donated by McCown to Wyoming Catholic College. WCC is cooperating with parties involved in the civil suit, and the funds are in the process of being returned.”

Arbery acknowledged in a July 12 telephone interview with the Register that the news had rocked the campus. He also emphasized that an initial investigation had not uncovered misuse of donor funds and that the college is complying with their legal obligations to respond to a subpoena.

“We are deeply hurt and heartbroken at this situation,” said Arbery.

“We are not aware at present of any misuse of donor funds. The money we are talking about was a gift to the college that showed up in the bank and we were planning to use it for future expansion.”

Arbery sought to offer reassurance that the setback to the college’s expansion plans did not pose an actual threat to the institution’s financial stability.

“It is more a disappointment with respect to the future plans of the college than something that threatens our day-to-day operations,” he said.

And as the school community comes to grips with the violation of trust, Arbery has already pointed to the alleged fraud to drive home the moral truths at the core of the college’s Great Books curriculum.

“In Dante’s Inferno, the Fifth Bolgia of the Eighth Circle punishes the sin of barratry. As one commentator puts it, “Baratteria is a medieval term no longer in use, which signifies fraud committed to obtain illicit gain to the detriment of one’s community,” Arbery explained in a recent column, “The Tar of Fraud,” for the wider school community.

“The punitive form of this particular pocket of hell is bubbling tar, the kind shipwrights use to make their vessels watertight—the opposite of what these grafters have been doing with their fraud, which is making the common good of the community leak away.

“But the image of tar works another way as well,” he added. “Fraud is sticky stuff. Even being in proximity to it can tar someone with suspicion. We will do all we can to keep that from happening in our community.”

Asked to address more detailed questions about McCown’s credentials and recruitment, Arbery said he could not offer further comment while the civil litigation continued.

According to the statement posted on the college’s website, it learned about the claims — described as “personal financial irregularities” — against McCown on June 3. Within 48 hours, he was placed on indefinite leave, and after the civil suit was filed on June 22, he resigned from his post on June 25.

A second employee of the college who was referenced in the suit has also been placed on administrative leave.

The Fraud Claims

Though the ongoing litigation prevented the college from providing more details or context regarding the allegations against McCown, the fraud claims in the civil suit have been widely covered by local news outlets.

The lawsuit filed by the investment firm, R Squared, Inc., alleges that its president and chief executive David Kang was told by McCown that he was looking for advisory services for the college’s endowment fund. But later, McCown said he also needed help with his own “substantial personal wealth,” and that subsequent bank statements appeared to document a big deposit boosting his personal funds to $750.3 million.

The lawsuit claims that McCown had manipulated his personal banking statements to misrepresent his wealth. The documents were then used to set up an account with R Squared, which subsequently approved short term loans to McCown totaling $15 million.

According to papers filed with the district court, within “hours or minutes” of McCown obtaining the loan, most of the funds had been distributed to his relatives and to himself, and he secured a cashier’s check payable to the state for $841,863. Further, Wyoming Catholic College received an anonymous gift of $10 million.

“This is the story of a complex, calculated, methodical and fraudulent scheme, orchestrated by an individual holding a trusted and respected position with the Wyoming Catholic College, to defraud R Squared out of the sum of $15 million,” reads the lawsuit.

McCown received the loan on May 11, but as R Squared waited in vain for their new client’s investment funds to be deposited with the firm, an investigation allegedly uncovered his complicated fraudulent scheme.

“The falsity, and the great lengths Mr. McCown took to exact his plan, became known only days after funding the loan,” the lawsuit said. “Regrettably, the vast majority of the funds have now been disseminated to various entities and individuals affiliated with Mr. McCown, including his family members and his employer.”

McCown graduated from Thomas Aquinas College in 2010, according to a Sept. 23, 2016, post on the TAC website. He later obtained a master’s degree in economics and public policy from Pepperdine University, according to a biography published during his successful campaign for a seat on the Troy, Michigan, city council. And he also served as executive vice president and CFO of Dataspeed, Inc., a company specializing in autonomous vehicles and mobile robotics.

While working at Wyoming Catholic College, he opened a local business, Sweetwater Spirits, LLC, which produced hand sanitizers during the pandemic, according to local news reports.

Cautionary Example

Now, as the college works to return the funds it received and continues its own investigation into the damage wreaked by its former chief financial officer, experts told the Register that the tangled case should serve as a cautionary tale for other Catholic institutions.

For example, though it is not clear whether the college knew that the anonymous donation had come from its CFO, Father Anthony Stoeppel, who teaches a class on church management at St. Patrick’s Seminary in Menlo Park, Calif., emphasized the need for checks and balances to maintain complete transparency and flag potential issues.

“A development policy may require a ‘reference check’ of major gifts to ensure giving capacity, especially those from an anonymous donor, before spending any money,” Father Stoeppel told the Register, while noting that he had yet to study the claims in the lawsuit. “Typically, the CFO would do the task, but in this case, since the donor is the CFO, a policy might state that in cases where there is a conflict of interest with the CFO the CEO conducts the check.”

Father Robert Gahl, associate professor of ethics and vice chair of the Program of Church Management at the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross, also told the Register that he had not “been able to follow this case closely.”

“Nonetheless, while it seems that WCC is mostly a victim in this affair,” he said, “it’s certainly indicative of how crucially important it is for Church institutions to be able to rely upon proficient, competent, and carefully vetted lay professionals to carry out tasks of management so as to exemplify the Church’s social teaching and to respect the generosity of donors by making the most of their gifts for the sake of evangelization.”

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity