Have you ever known someone who was facing a truly huge loss, and struggled with what to say to them?

It hit close to home lately. A friend lost someone close to him to suicide. It has completely rocked his world. At the funeral, I spoke to several people who really just didn’t know what to say. “Saying ‘I’m sorry’ just seems so inadequate.”

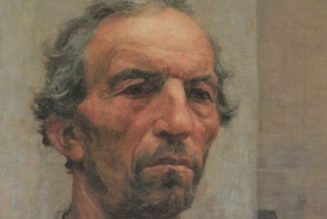

Yesterday, I picked up the beautiful book Cry of the Heart, taken from talks given by my late, brilliant professor and friend, Msgr. Lorenzo Albacete. The book is about suffering — written by a man who suffered deeply. Having gone through a few of my own losses in the past couple of years, I wanted to see what my beloved Msgr. Albacete had to say on the subject.

It was deeply moving.

And so, I thought he and I would team up one last time and address the question: how do we best love people through the most difficult moments of their lives?

Let me start by saying: it is true that “I’m sorry” is not adequate. But what could possibly be adequate? Is there really something we could say that would make everything okay again? Are there magical words that make suffering go away? Of course not. So we say “I’m sorry” and everybody knows it’s what we say. It works.

Then there are the things we shouldn’t say. Albacete uses the Book of Job to illustrate how not to respond to suffering. Job, as you may recall, loses everything — family, possessions, livelihood. His life is everybody’s nightmare. Nobody knows how to respond. So his friends respond by trying to fit his suffering into a theological system — to intellectualize it. Because what we explain in our brains can’t hurt our hearts, right?

– Advertisement –

It’s easy to understand that temptation. Maybe if we could give offer explanation, it might help. Or maybe we just want to feel better ourselves.

Albacete disagrees. He gets that, in the face of suffering, we sometimes want to offer “pre-packaged religious replies.” But he also says that to do so is insulting to the person who suffers. “The cruelest response to suffering is to attempt to explain it away, to tell the one who suffers, ‘This is why it is happening. I’m sorry you can’t see the answer, but it’s clear to me.’”

I agree. My mother died under tragic circumstances. People were lovely. They said “I’m sorry” and they listened and prayed and were generally supportive. But every once in a while somebody would come along and try to “cheer me up.” They’d offer some kind of (generally incorrect) explanation that they thought might make the blow easier to bear. Their hearts were in the right place. But it didn’t work. It annoyed me. It felt like an effort to minimize what happened, to deny my grief. After all, if it fits into a neat little box, there is nothing to grieve, is there? It didn’t make me feel better. I don’t think it makes anybody feel better.

Albacete offers an alternative. Speaking of Job, he writes “True friends would have acknowledged the horror he was going through, stood by him in his pain, and refrained from offering an answer to or a reason for his suffering.”

I think this is the finest summary of how to stand with suffering friends that I have ever seen. We acknowledge their experience, and we stay in it with them, without trying to minimize it or explain it away.

Albacete calls this “co-suffering.”

Co-suffering doesn’t mean that we enter fully into the suffering person’s experience. Suffering is intimately personal. It can’t be transferred. But when we stand side by side with them, when we walk with them through their grief, we do take on a certain measure of suffering for ourselves. It is not easy. But it is the only real way to love them. It is the price of admission. Albacete says “The one who does not co-suffer and is not prepared to do so cannot speak about suffering.”

But what do we say? How do we answer when they ask, “why me? Why did this happen?” That’s when it’s tempting to resort to those insulting pre-packaged religious responses. But suffering resists facile answers. Human suffering is a truly a mystery — a mystery we will never fully understand in this life. We don’t have those answers. Only God does. That is why Albacete says, “We can only help the other person to ask ‘why’ by asking it together — that is, by praying together.”

In the end, there is only one answer to suffering. And that, according to Albacete, is grace. “Suffering can be relieved by the co-sufferer only when the co-sufferer can bring the suffering person into contact with grace and into the experience of being loved. The answer to suffering will always be an experience of grace and love.”

And where do we find that experience of grace and love? In Christ. And especially, at the foot of his cross. The difference between our suffering and that of animals is that their suffering serves no higher purpose. That is why we “put them down” when they are in pain. But, as humans created in the image and likeness of God, our suffering can be joined to the sufferings of Christ, caught up in that greatest of all mysteries. Our suffering can be redemptive.

And once again we are back to our pre-packaged replies. “Just offer it up.” As if that makes everything okay. Redemptive suffering is still suffering. But it is suffering caught up in the mystery of Christ. We don’t explain it away. We look it in the eye, unblinking. We don’t cut and run. We stand with them, for as long as it takes.

It is true, nothing we can say is “adequate.” If it were, then pain would be merely “something to be fixed,” as Albacete says, and we would be the omnipotent fixers. But deep spiritual pain is not something to be fixed. It is a mystery. It is a road to be walked, with grace and with love and with God.

And we can accompany them on that path.