This article is part of a special report on the total solar eclipse that will be visible from parts of the U.S., Mexico and Canada on April 8, 2024.

Millions of people living in the 115-mile-wide path of April 8’s total solar eclipse—and the millions more who will travel to catch the awe-inspiring astronomical event—are crossing their fingers that the weather will cooperate.

For those anxiously refreshing the forecast page, the tough news is that cloud cover and precipitation are much trickier to predict than temperature. This is because the former involve so many small-scale processes in the atmosphere, and each of these factors can change quickly, hour-by-hour and even minute-by-minute. These processes “are incredibly difficult to predict even in real time,” says Greg Carbin, chief of forecast operations at the U.S. National Weather Service’s (NWS’s) Weather Prediction Center. So even on eclipse day itself there won’t be total certainty; when mostly clear skies prevail, stray clouds can still roll by during the several minutes of totality (as frustratingly happened to this writer while viewing the 2017 eclipse in Nashville, Tenn.).

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

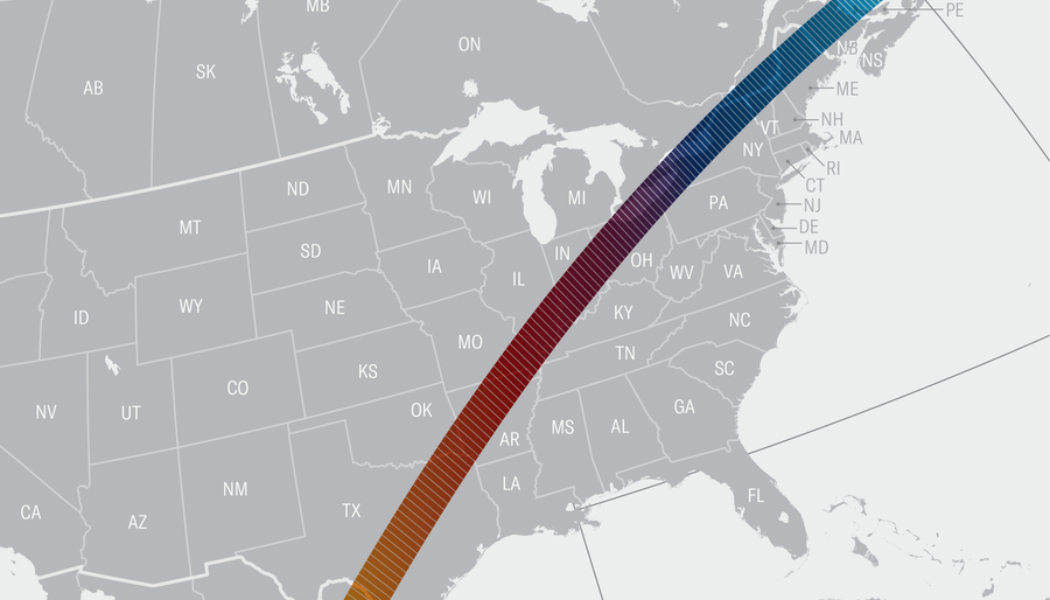

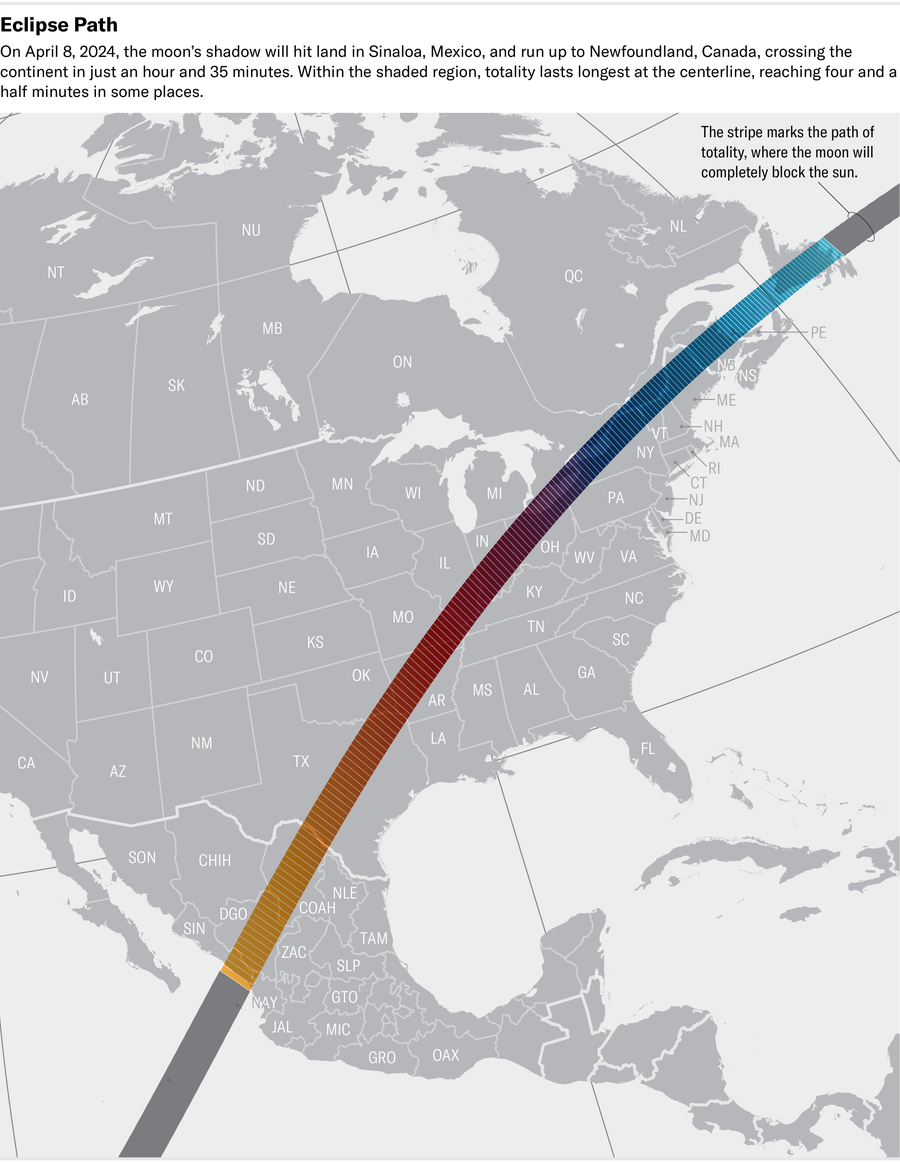

To help eager eclipse watchers prepare, Scientific American is keeping up with the daily forecast across the U.S. path of totality—which begins at about 1:27 P.M. CDT in Eagle Pass, Tex., and ends at about 3:35 P.M. EDT in Houlton, Me.—and is offering detailed information for a few major cities below. Forecasts will likely change, though, and when they do, we’ll be updating this article. So make sure to check back as the big day approaches.

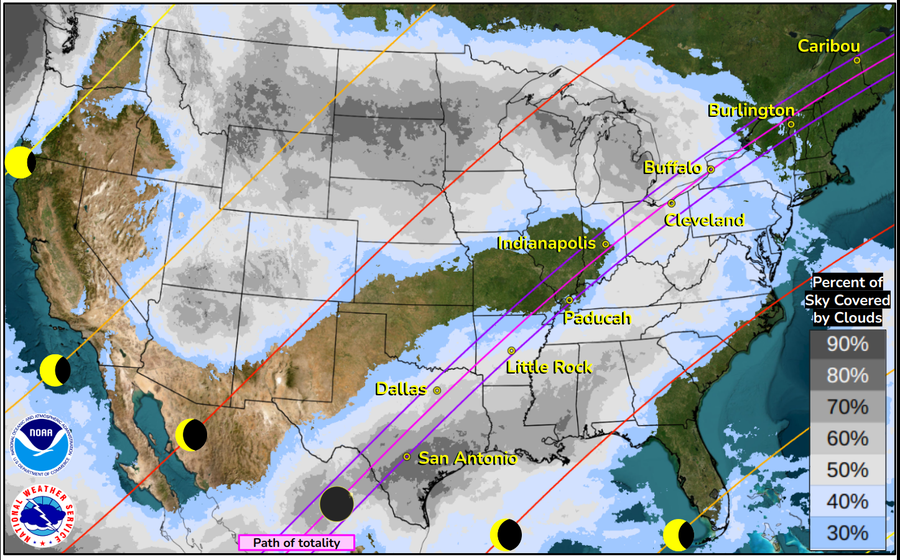

Based on climatology (the long-term average weather conditions in a particular place at a particular time of year), the best bet for clear skies will be in Texas, with the odds of cloudy conditions increasing as one moves northeast along the eclipse path. But those expectations, as shown in the graphic below, are just an average. Weather is inherently chaotic and especially so in spring. But current forecasts suggest the weather on the day of the coming eclipse could flip the climatological pattern.

Credit: Katie Peek; Source: NASA (eclipse track data)

Generally dry areas such as southern Texas are more likely to see clear skies at this time of year because there is less moisture available to build clouds. But near the Great Lakes and in New England, ground that is sodden from spring rains and lingering snow can provide ample moisture for clouds—especially when relatively warm spring breezes sweep through and promote evaporation.

April is part of “the transition season from the cool to the warm season,” Carbin says, noting that “the transition seasons are notoriously difficult” times in which to forecast weather. In part, this is because the jet stream—the vast, high-altitude river of air that guides storm systems across the continent—covers a good portion of the north-central U.S. Storm systems come with a higher degree of prediction uncertainty than stable air masses of high pressure, which generally bring clear skies. This year is particularly tricky, Carbin says, because the currently active El Niño climate pattern means another jet stream, known as the subtropical jet, is relatively active over the southern portion of the country.

The forecast right now shows a low-pressure system shifting into the Mississippi Valley by Monday—and these systems often bring clouds and precipitation. There is also an associated front, which separates warm and cool air masses, extending down into the south-central U.S., where it is expected to stall. Cloudiness and rain will affect the area ahead of the front and could bring severe weather to the total eclipse path in northern Texas.

Along the entire path of totality through the U.S., rainfall chances are currently highest in southeastern and south-central Texas, and there are lower chances between Arkansas and western New York State. The lowest chances are in New England. Likewise, cloudy conditions are highest from south-central Texas into Arkansas and in the lower Great Lakes, according to NWS. The best chances of clear skies are between southeastern Missouri and central Indiana and in northern New England.

But it’s still several days out, and how quickly the storm system moves over the country will determine who gets clouds and rain and when. Every run of the weather models has seen the system shift a little farther east, Carbin says. If that trend continues, conditions could improve for the Midwest.

Key Messages for 2024 Total Solar Eclipse.

Credit: NOAA’s Weather Prediction Center

Even as the broad patterns of the jet stream and air mass movement become clearer as Monday nears, “the devil’s in the details,” Carbin says. At best, forecasts on a given day can still only give expected conditions hour-by-hour—and the eclipse will happen on the scale of minutes. It’s impossible to say exactly where a downpour or a puffy cloud will pop up. Carbin likens it to a pot of boiling water: You know that bubbles will form, “but can you predict where that first bubble will come up?”

For those who do expect cloud cover on Monday, all is not necessarily lost: the NWS maps don’t say what kind of clouds might be involved. Rainy, overcast skies will certainly obscure views, but “high clouds alone may not block out the eclipse,” said NWS meteorologist Cody Snell during a briefing held by the agency on Wednesday. “So even if there’s some cloud cover in the forecast, all hope is not lost at seeing this astronomical event.”

And the eclipse itself could actually be a boon if puffy white clouds prove to be the only potential obscuration: a recent study found that in a 2005 eclipse over Europe and Africa, low-level cumulus clouds actually dissipated during the event. Such clouds form when warm, moist air rises from the ground, cooling and condensing into droplets. An eclipse’s blockage of the sun’s rays can quickly cool the land’s surface temperature—disrupting the cloud-forming process.

Below are the current forecasts for select cities on the eclipse’s path.

San Antonio, Tex. (Totality begins around 1:30 P.M. CDT)

Cloud cover in the area is currently projected to be about 60 to 80 percent, becoming higher as one moves from the northwest to the southeast, with showers and storms possible.

Dallas, Tex. (1:40 P.M. CDT)

Low, dense clouds are expected in parts of the area, and there will likely be at least some high clouds. The lower clouds will spread northward throughout the day, but the exact timing of this is uncertain.

Little Rock, Ark. (1:50 P.M. CDT)

Clouds and stormier weather are likelier to prevail in portions of southern Arkansas, with chances of drier, clearer weather in the state’s north.

Indianapolis (3 P.M. EDT)

This forecast is fairly uncertain, with some concerns for cloud cover during the eclipse—but the timing of the low-pressure system’s passage over the country will be a big factor.

Cleveland (3:15 P.M. EDT)

The odds favor clouds and possibly some rain, but conditions will depend on the timing of the low-pressure system.

Burlington, Vt. (3:25 P.M. EDT)

Clear, sunny skies and mild weather are expected.