‘Hope is the theological virtue by which we desire the kingdom of heaven and eternal life as our happiness, placing our trust in Christ’s promises and relying not on our own strength, but on the help of the grace of the Holy Spirit.’ (CCC 1817)

Hail Holy Queen, Mother of Mercy,

Our Life, Our Sweetness and Our Hope;

To thee do we cry, poor banished children of Eve;

To thee do we send up our sighs,

Mourning and weeping in this vale of tears …

On first appearance it might seem that hope is the least important of the theological virtues.

Love, it seems, is far greater. St Paul tells us that love is the greatest of virtues, and that those who “have not love” are nothing but “a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal”, and that those who “have a faith that can move mountains, but have not love” are “nothing.” Faith also seems to be greater than hope. Even faith as small as a mustard seed can move mighty mountains.

Hope, it seems, is destined to live in the shadow of its more illustrious brethren. It does so in humility, not merely in its willingness to be the servant of the servants of God but in its knowledge that “the last will be first, and the first last.”

Like the Trinity at the heart of reality, the theological virtues are One even as they are Three. Like their source, of which they are a reflection and a type, they exhibit the Divine egalitarianism. If, therefore, hope is the least of the virtues it is, paradoxically, the least among equals.

This convoluted paradox is exemplified by the fact that hope, as the “least” of the virtues, is the antidote to the poison of pride, the greatest of sins. Hope, as the humblest of the virtues, overthrows pride with humility. Where hope prevails, pride fails. Conversely, where hope is absent, pride prevails. Hopelessness is despair, and despair is the triumph of pride. Hope, the humble David of the virtues, slays the mighty Goliath of the sins.

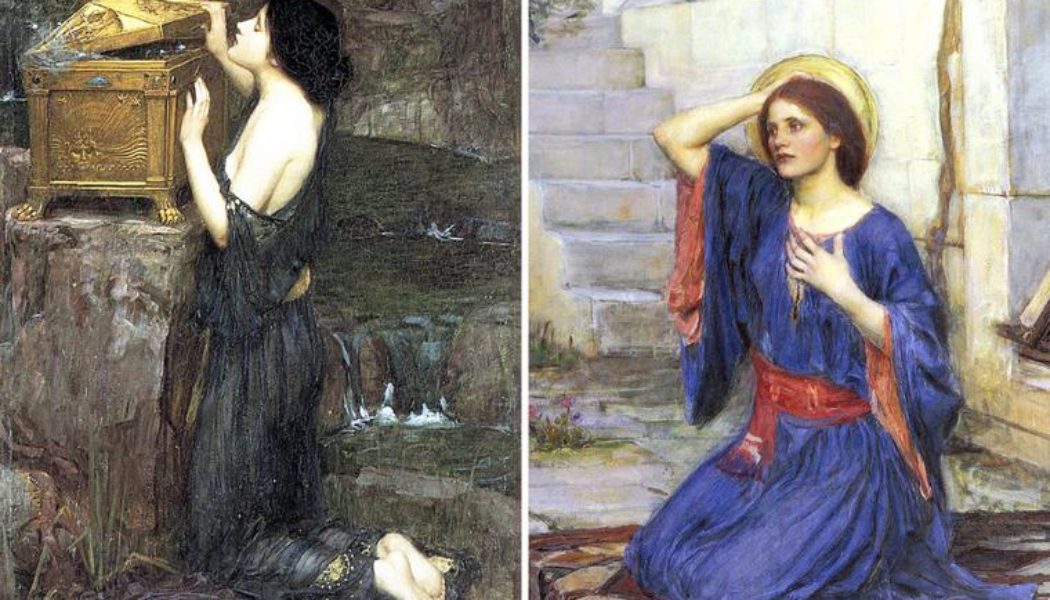

Hope also has a special place in pagan mythology, a place reserved for it in Pandora’s Box. In point of fact, the box was not Pandora’s at all. It belonged to the gods and she had no right to open it. As with Eve’s plucking of the forbidden fruit, Pandora, the pagan Eve, opens the forbidden box. The curse of this original sin plagues humanity as, like a cloud of licentious locusts, vice and disease pour forth from the opened casket. Only hope remains in the box, the silver lining in the cloud that overshadows fallen humanity.

There is so much truth to be discovered in the myth of Pandora’s Box that it’s a shame that “myth” is so often used as a synonym for “lie.” A lie is always a lie, but a myth is often true. I happen to believe in Pandora’s Box, not merely because of the metaphors and allegories to be found in it, but because I once found myself actually living in it.

Many years ago, or once upon a time, I found myself alone in a prison cell. It was during my own dark ages, before I was received into the Catholic Church. I was a leading member of a white supremacist organization, an angry young man, who had been sentenced to twelve months in prison for “publishing material likely to incite racial hatred.” It was during the first days of my sentence. I was in solitary confinement. I was alone; utterly, unspeakably alone. Or so I imagined. I was in fact surrounded by my own vices, my own sins, my own bitterness, my own hates. A plethora of plague-ridden doubts besieged me. My prison cell was Pandora’s Box.

I had no faith, so I thought. I had no love, except for that love for family and friends that even the publicans and sinners have. And yet, hidden somewhere in the corner of my Pandora’s Box was the barest flicker of hope.

Someone had sent me a rosary. I had no idea what to do with it. I was not a Catholic, though the reading of Chesterton and Belloc had led me closer to the arms of Mother Church than I realized. I didn’t know the Hail Mary or the Apostles’ Creed or the Glory Be. I had been taught the Our Father many years earlier, at school, but had long since forgotten it. I had never prayed before in my life. What was I to do with this string of beads?

It was then, in the midst of “the earthquake, wind and fire” of my sinful passions, that I heard that whispering hope, the “still, small voice of calm” that would exorcise the demons and still the waters of my heart. It was hope that guided my fingers from bead to bead; it was hope that formed the mumbled, barely articulate prayers onto the lips of my mind. It was hope that brought me the first inklings of the peace to be found in Christ. It was hope that taught me humility. It was with this thinnest thread of hope that I climbed downwards to my knees.

That was a long time ago. I have long since learned to say the Rosary. I have long since learned to honor the Mother of God with the many anthems sung in her honor. I have come to understand that she is the one who allowed God himself to repair the damage done by Eve (and Pandora). She is truly “our life, our sweetness, and our hope.” And I have learned that hope is the very sweetness of our life.

Turn then, most gracious advocate,

Thine eyes of mercy towards us,

And after this our exile,

Show unto us the blessed fruit of thy womb, Jesus.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity