Trigger warning: child loss.

Eleven months ago today, my family suffered the unspeakable tragedy of losing our 6th child, Margaret, to Down Syndrome. What we expected to be the joyous birth of — by all accounts — our healthy baby girl was in an instant turned into the devastating, heart-wrenching pain of loss. In the early morning hours, my wife had felt her kicks; by the time we arrived at the hospital, a routine we’re all too familiar with now, her little heart had failed.

A month from now, on the anniversary of her death, I don’t expect to be writing anything. My wife and kids I will hold close as we visit her grave and think of her, as we torture ourselves with tearful thoughts of what might have been and console each other with the comfort that she is with God. In lieu of any meaningful reflection at the 1-year mark, I wanted to share 11 things — for these 11 months — I want everyone to know about child loss, about grief, about still birth, about Down Syndrome, and I hope my readers can grow from sharing my experience as much as I have in all this time.

- Death is sudden. I know this is a cliche. I know it’s obvious. I know anyone with a little life experience is aware how fleeting life is and how fickle fortune may be. Yet it bears repeating: death is sudden. One moment, we expected the day to be full of happiness and sweetness; the next, we were in our darkest hour. It can happen to us ourselves, too, when we die. Live today so that when you die, you are not suddenly cast into darkness. Live in the light, so that when death does find you, it finds you as a friend.

- The pain of losing someone is very much bound up in the pain of cognitive dissonance. We expect someone to be there. We know they will be there. We have memories of grandparents. We have dreams for our children. We all experience or envision our lives a certain way, a way we come to rely on, and when someone dies, our expectations are ruptured — violently. All throughout the day we lost her, I looked down and found my arms in a cradling position. My subconscious, my muscle memory, they were telling me that I fully expected to be holding my baby. The reality, by contrast, was a knife to the heart.

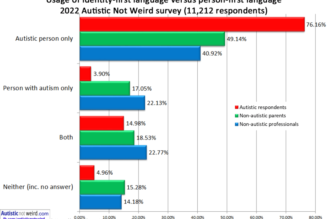

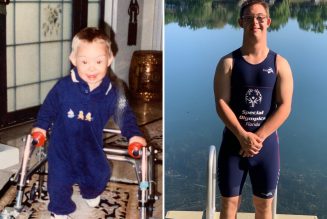

- Seeing persons right can take an effort. When I saw my little girl, I immediately recognized the problem. I just blurted out, “this baby has Down Syndrome.” We hadn’t known that. It was a shock. So my brain didn’t expect it and at first, I didn’t see this as “my baby” but as “this baby.” I stopped for a moment, realizing what I had said. I scanned her face and found her nose. All our kids have my wife’s nose. So did she. “My baby,” I said as I kissed her forehead. “My poor baby.”

- Hospital personnel are trying to cope, too. The nurses who first discovered something was wrong tried so hard to avoid trampling on our emotions. Bless them, as if such a thing were possible. We’ve been through the whole birthing thing a few times, we know how to listen to a Doppler or read an ultrasound. We knew what was happening. The anesthesiologist kept asking me mundane questions about all sorts of unrelated things while my wife was birthing our deceased daughter. It was awkward, but I don’t blame him. What could he say? Even the nurse who kept pushing my wife — immediately — to pick a funeral home. Was it grossly unprofessional bedside manner? Absolutely. But I think some people cope that way; they cling to procedure.

- Kids all react differently. It was my job to drive home and tell her siblings — our kids — that their sister had died. The older kids suspected something was wrong because I hadn’t sent pictures. The younger kids reacted only when I said exactly what was going on. The very youngest just ran around laughing and playing like nothing had happened. I had to stick around a couple hours and help them process before I could return to my wife. Every one of them had a different way of coping. The hardest was the barely 6yo girl who ran off crying to her room, where she locked herself in.

- Friends and family will surprise you. It was that upset 6yo’s cousin — a gruff, buff, redhead but somehow deeply tan, ex-Navy football coach who played in high school alongside Dak Prescott, the kind of man who would terrify most children — who talked her out and got her to open up. Meanwhile, some other family members we held closely tried to turn our loss into an opportunity for their own attention-seeking.

- Even strangers will surprise you. It wasn’t common, but a few people on the internet congratulated us on our stillbirth. There’s so little civility these days. One woke person took the opportunity to lecture me on not making Down Syndrome sound like a negative. “It’s a blessing in disguise,” he said, apparently (painfully) unaware that it had taken my daughter’s life.

- Stillbirths cost more than live births. “Average hospital costs for women with stillbirth were more than $750 higher than women with live births but length of stay was not significantly different between the two,” report the National Institutes of Health. That’s right, despite the same or less time and no infant care involved, it’s significantly more expensive to have a stillbirth — before considering burial costs. There’s just something seriously wrong with that, don’t you think?

- Burial costs vary. Our little girl was spared a plot fee because the law allowed us to bury her small casket above the remains of her grandfather — a virtual saint among men I absolutely know would have doted heavily on our Down Syndrome daughter if both had lived. She was also spared all but cost by the funeral home, a very kind and appreciated gesture. However, we still had to pay hundreds of dollars for someone to spend 20 minutes digging a hole with a backhoe.

- People are generous. I say “we still had to pay,” but the truth is that every cost was taken care of, largely by internet friends we don’t even personally know. My wife and I remain incredibly grateful to them all and the love from strangers continues: just last week, someone sent us $100, knowing we didn’t need it any longer, just because she wanted to have a share in supporting us. How kind. At a time when, as I said, even some family members have been unbearable toward us, it’s good to know that human kindness remains.

- God is still good. Shortly after we lost her, my wife looked at me with tears and said, “I don’t blame God.” I didn’t either. In a general sense, death is due to sin; it’s not God’s plan for us and He doesn’t deserve the blame. It wasn’t Margaret’s fault, either; she hadn’t committed any personal sins. The results of human fallenness are the inheritance of us all. Yet even in our pain, God has been with us. He has even worked some timely signs for our consolation. (Sure, I’ll claim St. Margaret of Castello’s canonization as a victory for our little Margaret. Why not?)

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity