Notes from the Author:

1) First and foremost–I offer this post to Our Lord through the intercession of His Mother and Sts. Lazarus, Mary, and Martha: in reparation for my sins and the sins of the world, for our repentance, and for an enduring peace throughout the Middle East and the world as quickly as possible.

2) It has been a while since I have posted. My previous post can be read here: https://zistezesto.wordpress.com/2023/05/20/chapter-4-exploring-little-and-some-well-known-sites-in-the-holy-land-mass-in-christs-tomb-the-head-of-st-james-the-sky-path-of-the-paraclete-the-riddle-of-siloam/

3) As a reminder, copy/paste GPS Coordinates listed below into Google Maps to see or travel to each location.

4) I apologize for any annoying ads wordpress.com automatically and randomly posts within this article–they are not of my choosing.

5) Lastly, if you enjoy this post and want to learn more, check out my one-of-a-kind book, The Second Person of the Trinity in Time and Space: What is Known Historically About Jesus and the Holy Sites of the New Testament, sold on Amazon.com! (link at the bottom of this post)

After visiting Siloam, I traveled back up to the Old City of Jerusalem to continue visiting important sites of our faith.

The next site I visited was the southeastern corner of the Old City. It also happens to be the southeastern corner of the Temple Mount as well.

This corner is more famously known, however, as the “Pinnacle of the Temple.” (GPS Coordinates: 31°46’33.92″N, 35°14’15.24″E) This was the place where satan took Jesus and tempted Him to test God by throwing Himself off of this wall so God could save Him (ref. Matthew 4: 5-7, Luke 4: 9-12). It is a very high wall and would have been a very long way to fall. A church once stood at the top of the corner, which commemorated Christ’s overcoming of this temptation.

Many people also do not know that the Pinnacle of the Temple is also the place of St. James the Less’s (Jesus’s cousin and First Bishop of Jerusalem) martyrdom. In Book III, Chapter 23 of The Church History, written by the bishop of Caesarea Maritima, Eusebius, in around A.D. 325, he recounts the death of St. James by quoting an even earlier Church historian by the name of Hegesippus:

“The aforesaid Scribes and Pharisees therefore placed James upon the pinnacle of the temple, and cried out to him and said: ‘You just one, in whom we ought all to have confidence, forasmuch as the people are led astray after Jesus, the crucified one, declare to us, what is the gate of Jesus.’

And he answered with a loud voice, ‘Why do you ask me concerning Jesus, the Son of Man? He himself sits in heaven at the right hand of the great Power, and is about to come upon the clouds of heaven.’

And when many were fully convinced and gloried in the testimony of James, and said, ‘Hosanna to the Son of David,’ these same Scribes and Pharisees said again to one another, ‘We have done badly in supplying such testimony to Jesus. But let us go up and throw him down, in order that they may be afraid to believe him.’

And they cried out, saying, ‘Oh! Oh! The just man is also in error.’ And they fulfilled the Scripture written in Isaiah, ‘Let us take away the just man, because he is troublesome to us: therefore they shall eat the fruit of their doings.’

So they went up and threw down the just man, and said to each other, ‘Let us stone James the Just.’ And they began to stone him, for he was not killed by the fall; but he turned and knelt down and said, ‘I entreat you, Lord God our Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.’

And while they were thus stoning him one of the priests of the sons of Rechab, the son of the Rechabites, who are mentioned by Jeremiah the prophet, cried out, saying, ‘Stop. What are you doing? The just one prays for you.’

And one of them, who was a fuller, took the club with which he beat out clothes and struck the just man on the head. And thus he suffered martyrdom. And they buried him on the spot, by the temple, and his monument still remains by the temple. He became a true witness, both to Jews and Greeks, that Jesus is the Christ.”

As I stood at the foot of the Pinnacle of the Temple and I tried to imagine this scene–St. James’s broken but still functional body being smashed further with stones. Despite his injuries, he still had the strength to kneel and pray for his persecutors before having his skull beaten with a club. A green artificial turf now covers the base of the Pinnacle of the Temple…the place where Christ Himself must have looked down upon when being tempted by satan and where the blood of the Apostle and first Bishop of Jerusalem was shed. Ironically, massive churches have been constructed and remain to this day over the places of other martyrs’ deaths, but mysteriously not so for the pious St. James. St. James, pray for us!

After viewing the Pinnacle of the Temple, I walked back towards the famous Western Wall (also known as the “Wailing Wall”) which is Judaism’s holiest shrine–a part of the ancient retaining wall below the Temple Mount which gave form to the platform upon which the Jewish Temple once stood. Jews come to the Wall to worship and remember their Temple that was destroyed by the Romans in A.D. 70. The Muslims would later capture Jerusalem from the Christian Byzantine Empire (the Eastern Roman Empire) in around the year A.D. 638 and build a mosque–the Dome of the Rock over the previous site of the Temple. Today Jews and Christians are not permitted to worship atop the Temple Mount as only Muslim worship is allowed there now.

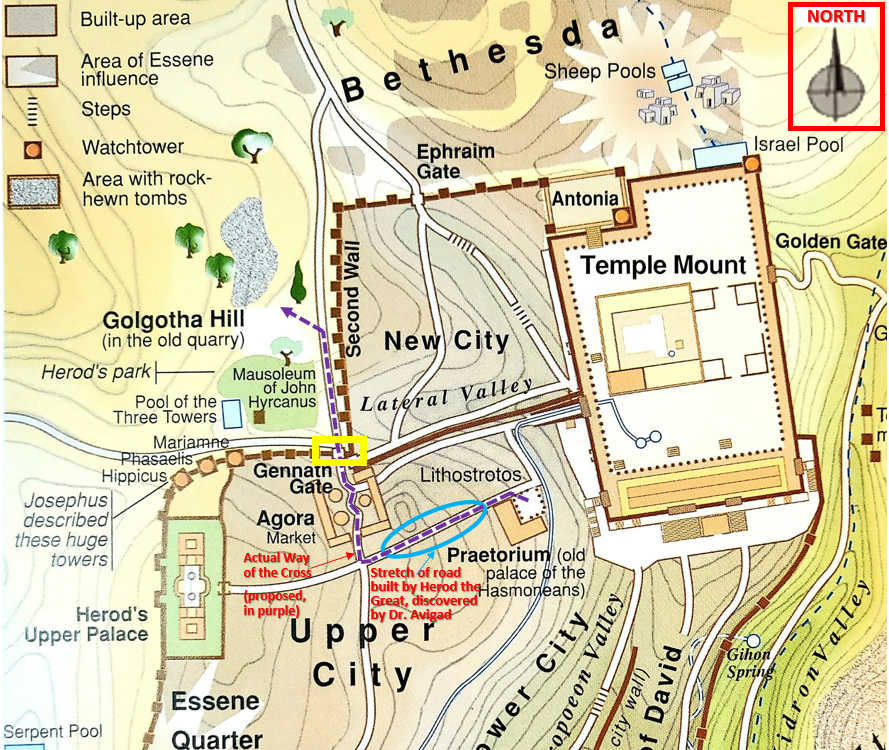

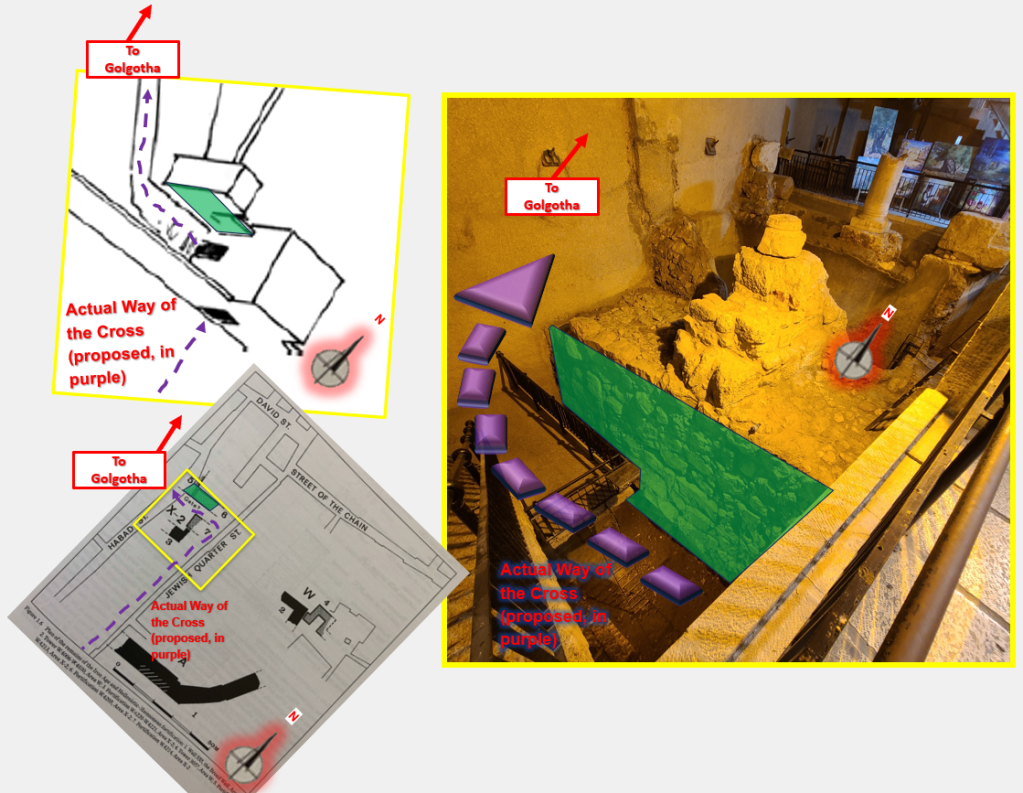

However, my destination was the opposite edge of Jerusalem’s central valley (known as the Tyropoeon Valley) from the Western Wall. It was in this approximate location the Praetorium of Pontius Pilate stood where Christ was brought before Pilate, scourged, crowned with thorns, condemned to death, and given His cross.

Some readers may be confused by my last statement, thinking to themselves: “doesn’t the traditional Via Dolorosa start north of the Temple Mount?” The answer to this question is both “yes” and “no”!

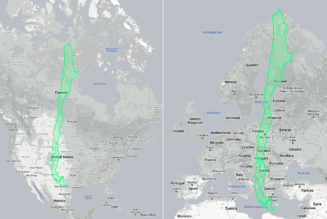

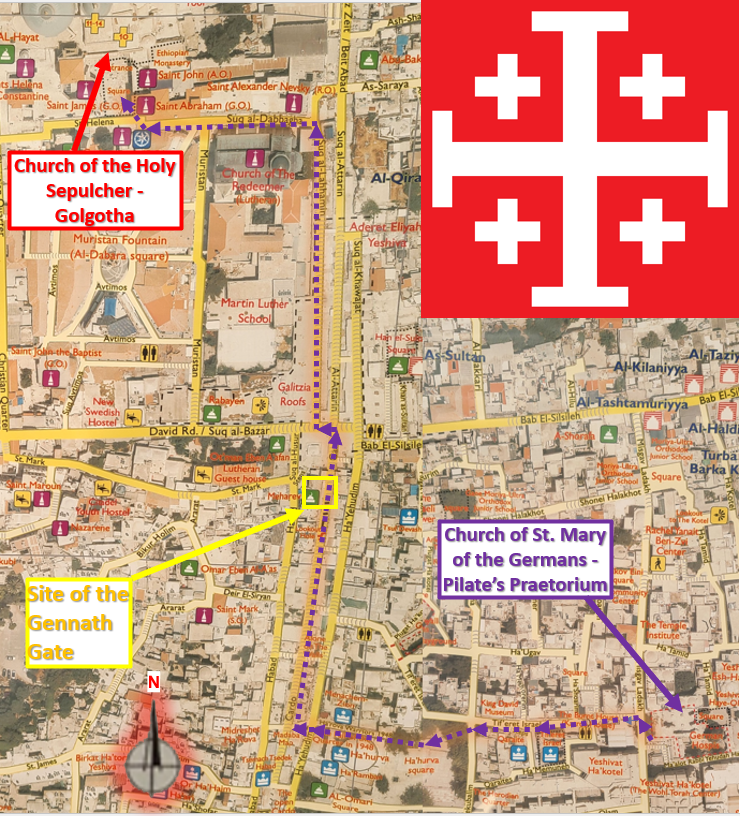

The starting place of the Via Dolorosa north of the Temple Mount and winding to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher is the path that has been followed by Christians for hundreds of years to commemorate Christ’s death. However, the fascinating truth many Christians don’t realize is the tradition linking this route with Christ’s Way of the Cross has only been around since the Crusader Era (approximately 800 years ago); it was established with good intentions by the Crusaders, but without access to the body of historical and archaeological evidence we have today. The Crusaders’ Way of the Cross has been devotedly maintained ever since but, believe it or not, before the current path came into use, Good Friday processions had already followed three separate paths. Each path was used during different spans going back thru time: one used from the 12th down to the 8th Centuries, one from the 7th to the 5th Centuries, and one from the 4th Century (Image 3 below shows the processions from the 5th Century to the present).

So what was the *actual* route Jesus took? Let’s explore the evidence…

A Short History of the Devotional Via Dolorosa Procession

We hear about the earliest historically documented Via Dolorosa path from the Spanish pilgrim nun Egeria in A.D. 380 (the 4th Century). She recounts that during Holy Week, there was a procession from Gethsemane through Jerusalem’s “Golden Gate” (the city’s east main gate) and straight west to Golgotha for the procession’s last stop. This path was, therefore, very direct, and it appears officials in Jerusalem at the time may have been deliberately choosing not to add additional stops along the route.

Next, the path used from the 5th to the 7th Century is documented in an Armenian Lectionary from the 5th Century. This path had the most stops of the ancient paths, beginning at Gethsemane and then traveling to the site of Caiaphas’s palace, the “Palace of the Judge” (i.e. the Praetorium of Pontius Pilate), and then finally stopping at Golgotha.

The conquest of the Holy Land by the Sasanian Persians in the 7th Century brought the destruction of many of Jerusalem’s churches; not long after, the Holy City came under the control of the Muslims of the Rashidun Caliphate. These events drove the Christian community of Jerusalem to change the starting point of their Way of the Cross procession west to Mount Zion, to the stone courtyard (a new “Stone Pavement” from John 19:13) in front of a small chapel dedicated to the Alexandrian martyrs Sts. Kyrios and John. This new route led from Mount Zion directly to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. This new route was used starting in the 8th Century and was also even used by the Crusaders for a time after they conquered Jerusalem at the end of the 11th Century.

However, the Way of the Cross would change once again during the Crusader occupation of Jerusalem in the 12th Century. According to Holy Land archaeologist Fr. Bargil Pixner in his 2010 book Paths of the Messiah and Sites of the Early Church from Galilee to Jerusalem, not all of the Crusaders were pleased with the “improbable location of the Praetorium” at the stone courtyard of Sts. Kyrios and John on Mount Zion. Fr. Pixner states “In the year 1172, a [Crusader] knight called Theodoric suggested another possibility. Near the Jerusalem headquarters of the Knights Templars at the north end of the Temple Mount, the ruins of the [Roman] Antonia fortress had been found. Theodoric stated that this, according to [the First Century Jewish Historian] Josephus, had been the authentic Palace of Pilate. This ‘discovery’ convinced an increasing number of Christians and the place on Mount Zion was eventually given up….This was the beginning of a completely new local tradition. The Franciscan Ricoldus de Monte Crucis was the first to describe the different Stations of the Cross from the Antonia fortress to Golgotha in the year 1294….Over time, all 14 Stations of the Way of the Cross were established as we now know them.” (2010, 311-313).

Candidates for Pilate’s Praetorium

It is a very curious thing that the route used to commemorate Jesus’s grueling procession to Golgotha has changed so many times over the last 2,000 years. Thankfully, history shows us the end point of the Way of the Cross has remained consistent–the Church of the Holy Sepulcher–but its start point–the location of Pilate’s Praetorium–not so much. To try to pinpoint the historical location Pilate used for his Praetorium, we need to examine the earliest evidence first from a source who wrote about the layout and buildings of 1st Century Jerusalem: a Jewish historian named Josephus (referenced earlier).

In his writings, Josephus describes three main civic buildings in 1st Century Jerusalem. The first is the splendid “Upper Palace” of Herod the Great, which was located on the western side of Jerusalem’s Old City. Herod used this palace as his residence in Jerusalem. When the Romans took direct control over the territory of Judea from Herod’s son, Archelaus, this palace became the residence of the Roman governor whenever he visited Jerusalem from his capital at Caesarea Maritima—53.6 miles away as the crow flies. Many modern scholars argue *this* (or adjacent to it) was the actual location of the praetorium since it is known the Roman governors would have resided here when they came to Jerusalem to oversee law and order operations during the Passover. Josephus also writes that the throne of judgment was set up here for the trial of Jewish rebels.

The next civic building Josephus mentions is the Antonia Fortress (referenced earlier). Also built by Herod the Great and dedicated to Mark Antony, this fortress was attached to the northwest corner of the Temple Mount. It served as a barracks for Roman soldiers stationed in Jerusalem and had a passageway that gave the soldiers direct access to the Temple Mount. If a riot or other disorder began to break out–especially during Jewish holidays when pilgrims would have flooded the Mount–the soldiers would have been able to quickly saturate the area in great numbers to crush any uprisings. The remains of this fortress were discovered by the Crusaders after they had conquered Jerusalem.

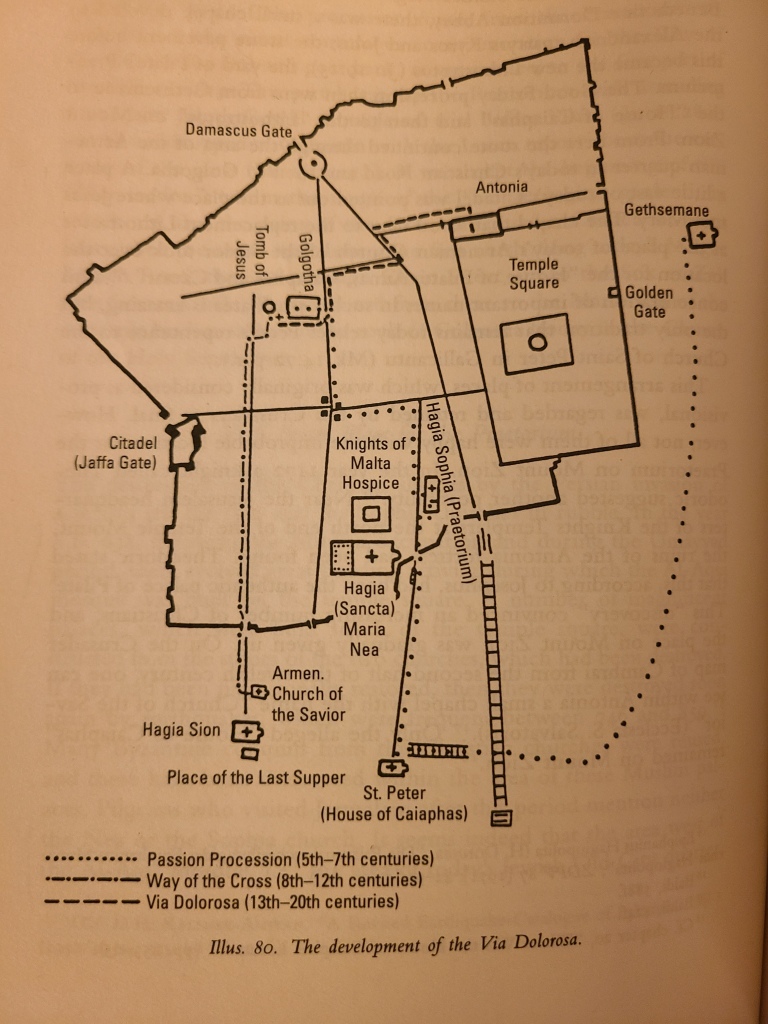

The last main civic building that Josephus mentions is known as the “Hasmonean Palace.” This palace was the residence of the Hasmonean Kings, the rulers of Judea before Herod the Great overthrew them. This palace served as Herod’s residence in Jerusalem until his new Upper Palace was completed. Josephus mentions the Hasmonean Palace several times in his writings. He indicates this palace overlooked the Temple Mount and would thus have been located atop the western ridge of the Tyropoeon Valley (the valley that runs through the middle of Old City Jerusalem–the Western/Wailing Wall is on the east side of this valley, the Temple Mount is also known as Mount Moriah–see Image 4 below).

Based on careful analysis of the extant evidence we have (which I will list below), of these three buildings, the Hasmonean Palace was most likely Pilate’s actual Praetorium and the starting point of Christ’s Way of the Cross.

Evidence the Hasmonean Palace was used as Pilate’s Praetorium

Evidence shows the Hasmonean Palace was likely used as the default administrative center (i.e. city hall and courthouse), for Jerusalem in the 1st Century, instead of Herod’s Upper Palace or the Antonia Fortress. The former was used as an official residence for Roman governors, and the latter served as a barracks:

-According to Pixner, “Herod [the Great] resided only in the Hasmonean Palace and not in the fortress Antonia [from 37 to 23 B.C] ([see Josephus’s Antiquities of the Jews] 15.292). It is also reported that it was in this palace that he exercised judicial office when he uncovered a conspiracy ([see Josephus’s Antiquities of the Jews] 15.286)” (Pixner 2010, 269). It seems that once Herod finished constructing his new Upper Palace after 23 B.C., the Hasmonean Palace was probably utilized for administrative purposes, and the Upper Palace for living…similar to Herod’s living and administrative arrangements at Masada, Jericho, and Caesarea Maritima” (Pixner 2010, 270).

-In Philio of Alexandria’s On the Virtues and on the Office of Ambassadors. Addressed to Caius. (known also as Legatio ad Gaium), he wrote that Pilate had golden shields or plaques mounted in “Herod’s palace” in Jerusalem and this provoked a riot by the Jews–this palace is also referred to by Philio as “the house of the governor.” Since Philio only specifically designates Herod’s Palace as Pilate’s “house” while in Jerusalem, this could be an indicator (albeit in absentia) that another facility was used for administration.

-Pixner and R. Jaeckle both state there is evidence if a Roman governor had his wife with him, there should be two praetoria used (Pixner 2010, 291). In Matthew 27:19, it appears Pilate is in a separate location some distance from his wife. This therefore strengthens the theory Pilate would have resided in Herod’s Upper Palace with his wife, but probably would have used the Hasmonean Palace for administrative purposes, as Herod had before he moved into his Upper Palace after 23 B.C.

-In Luke 23:7 & 11, it also appears Herod is in a separate building from Pilate. Luke remarks that Pilate “sent Jesus up to Herod” which indicates Herod may have been staying in the palace in the upper city to the west—the same large palace complex Pilate and his wife were residing in Jerusalem (Pixner 2010, 271).

-R. Jaeckle also points out praetoria would normally be in the center of a city. Having a praetorium in the center of a city would make the “seat of government” more defensible if an armed insurrection were to break out, when compared to situating it on the edge of the city (as the Upper Palace of Herod would have been situated) (Pixner 2010, 291). The Hasmonean Palace also would have been closer to the Roman garrison of soldiers at the Antonia Fortress than the Upper Palace, making the Hasmonean Palace more defensible for the governor in case his decisions at the praetorium from his “judgment throne” were not well-received by the local populace.

-As touched on previously, Josephus makes a statement in his history Wars of the Jews about a situation in A.D. 66 (33 years after Jesus’s death), where the judgment chair in Jerusalem was “set up” in Herod’s Upper Palace (See Josephus’s Wars of the Jews 2.301-308). If the Upper Palace was already used as a Praetorium, there shouldn’t have been a need to “set up” a judgment chair, thus giving us another piece of evidence that it was normally at another location–probably the Hasmonean Palace (Pixner 2010, 271).

Historical Sources and archaeological evidence indicate the general location of the Hasmonean Palace–the same general location of the site venerated by Christians as Pilate’s Praetorium.

In addition to the Hasmonean Palace being the best candidate for Jerusalem’s default administrative and judicial center at the time of Christ, historical and archaeological evidence, as listed below, show its relative location also happens to be the same location venerated by some of the most ancient Christian pilgrims as the site of Pilate’s Praetorium.

-Josephus discusses the location of the Hasmonean Palace in Antiquities of the Jews 20.189-190: “About the same time King Agrippa built himself a very large dining-room in the royal palace at Jerusalem, near to the [western] portico [of the Temple Mount]. Now this palace had been erected of old by the children of Asamoneus and was situated upon an elevation, and afforded a most delightful prospect to those that had a mind to take a view of the city, which prospect was desired by the king; and there he could lie down, and eat, and thence observe what was done in the temple.” This description points to a location on the western height of the Tyropoeon Valley near the western side of the Temple Mount, the same area where early Christian tradition placed the Praetorium of Pilate and the Sancta Sophia. According to Pixner, the raised position of this location made it “an ideal place for a king’s palace” (Pixner 2010, 273).

–St. John himself qualifies this identification further in his Gospel. According to Dr. Michael Pakaluk’s superb new translation of St. John’s Gospel in Mary’s Voice in the Gospel According to John, John 19:13 reads “So Pilate…led Jesus outside (the Praetorium). He sat down on a judgment seat, in the area called the Stone-Pavement (Lithostrotos in Greek), and in Hebrew called Gab Baitha” (Pakaluk 2021). Despite what many may think, “Gab Baitha” or “Gabbatha” is not the Aramaic word for “Stone Pavement,” but instead, according to commentary by Scott Hahn and Curtis Mitch in the Ignatius Catholic Study Bible New Testament, Second Catholic Edition RSV, Gabbatha is a Semitic expression which “refers to some sort of elevation” (Hahn & Mitch 2010, 197).

-In Wars of the Jews 2.344, Josephus also mentions an account of Herod Agrippa II negotiating with the Jews not to go to war with the Romans: “He therefore called the multitude together into a large gallery, and placed his sister Bernice in the house of the Asamoneans, that she might be seen by them (which house was over the gallery, at the passage to the upper city, where the bridge joined the temple to the gallery).” This description not only points to a location east of the upper city and on the western ridge of the Tyropoeon Valley across from the temple, it also makes mention of a large “gallery” fit to hold a “multitude” of people. If one swaps the place of Agrippa II with Pilate and Bernice with Christ, the description of this place appears to be describing the place of the Praetorium from the Gospels. The Greek word Josephus uses to describe the group of people who assemble in the gallery is “πλῆθος – plethos,” which means “multitude.” St. Luke uses this same Greek word in Luke 23:1 to describe the group of people who brought Christ before Pilate on Good Friday.

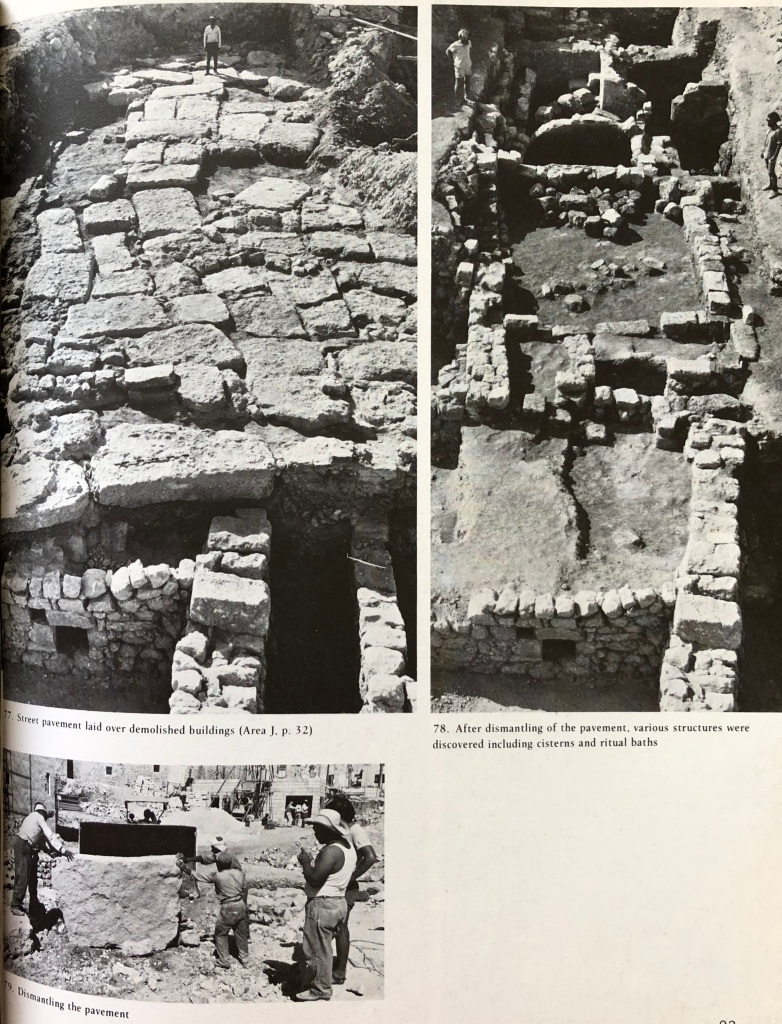

-Also according to Josephus’s Antiquities of the Jews 15.410, there was a road leading from the Coponius Gate (one of four gates on the Temple Mount’s western side) to at least one of Herod’s palaces. This gate is north of the Hasmonean and Upper palaces and the westbound road leading from the gate may have turned towards the southwest to the Hasmonean Palace. From the area where the Hasmonean Palace would have been, a road buried several feet underground was discovered by archaeologist Nahman Avigad in the 1970s. This road was paved with large stones and was well built. According to one of Avigad’s companions, Dr. Hillel Giva, the latest coins found underneath the flagstones of this street dated to the time of Herod the Great (who died in late Winter/early Spring in 1 B.C.), thereby dating its construction to Herod’s reign. Dr. Giva stated the road was built to connect Herod’s [upper] palace with the Temple Mount. This road system would have been necessary to give the king and his entourage/soldiers easy access from his new residence in the Upper Palace, to the Hasmonean Palace, and then to the most spectacular gate on the western side of the Temple Mount (the Coponius Gate) which led directly to the top level of the Temple Mount and the Temple itself.

Given the remarkable size of the road and its large flagstones, it is not much of a stretch to believe the Herodian construction project that created this road may have also included the area where Pilate’s judgment throne was (ref. John 19: 13–the “Stone Pavement”). The Hasmonean Palace (i.e. Pilate’s Praetorium) with the open area of “Stone Pavement” would have been close by this road and/or the “Stone Pavement” could have been connected to it. John 19: 13 reads: “So Pilate…led Jesus outside. He sat down on a judgment seat, in the area called the Stone-Pavement, and in Hebrew called Gab Baitha.” (Pakaluk 2021). The fact this place was known specifically by its type of paving leads one to believe it was an impressively paved area, which correlates to the “well built and wide” road, which must have been close by.

-According to Josephus, Pilate also had an aqueduct installed that ran from Bethlehem, immediately to the east of the Hasmonean Palace to the Temple (Vincent documents archaeological evidence of this aqueduct in his excavations in 1914–see Vincent 1914, 430). According to Pixner, it is thought by K. Jaroš that the Jews may have rebelled not only because Pilate used Temple money to fund this aqueduct (See Josephus’s Wars of the Jews 2.175), but also because the Romans in the Hasmonean Palace were using the water for their baths that then led to the Temple (Pixner 2010, 271). Pilate directed his soldiers to attack Jewish protesters from his “throne of judgment” (See Josephus’s Wars of the Jews 2.175 – 77 and Antiquities of the Jews 18.60-62). Josephus and Matthew happen to use the same Greek word to describe this “throne” of Pilate.

-After the Gospels and other contemporary historical sources, the earliest traditions mentioning the praetorium of Pilate appear in the Bordeaux Pilgrim’s account (written in A.D. 333) which says the following about the praetorium: “[as you go north from Mount Zion] down in the valley on your right you have some walls where Pilate had his house, the Praetorium where the Lord’s case was heard before He suffered” (Translation from Wilkinson’s Egeria’s Travels, 1971, 31). In approximately A.D. 347, the Bishop of Jerusalem, St. Cyril, mentions in his Catechetical Lecture 13 that the praetorium was currently still in ruins: “the hall of Pilate, now laid waste by the power of Him who was then crucified.” In the Armenian Codex, written between A.D. 417 and 439, which documented liturgical practices in Jerusalem at the time, we see “the Palace of the Judge (Pilate)” included as a station in commemoration of the Passion for the first time. Peter the Iberian, writing in around the year A.D. 500 was the first source to mention a church over the site and Theodosius, writing in approximately A.D. 518 first calls the church the Church of St. Sophia/Holy Wisdom (or “Sancta Sophia” in Latin).

–Theodosius also gives distances between different holy sites in his topographical account of the Holy Land:

“From the House of Caiaphas to the Praetorium of Pilate it is about 100 paces; the Church of Saint Sophia is there. Beside it Saint Jeremiah was cast into the pit.”

…

“The Pool of Siloam is 100 paces from the pit where they cast the Prophet Jeremiah: it is inside the wall. From the House of Pilate it is about 100 paces to the Sheep-Pool. There my Lord Christ cured the paralysed man, whose couch is still there. Beside the Sheep-Pool is the Church of my Lady Mary” (Translation from Wilkinson’s Jerusalem Pilgrims, 2002, 107, 109).

Although the distances in paces cannot be precise (especially taking into account changes in elevation along routes, whether or not Theodosius was estimating the distance “as the crow flies” or by following roads, etc.), Theodosius’s distances do seem to indicate 1) the Praetorium was about halfway between the “House of Caiaphas” and the site of Bethesda (the Sheep Pool mentioned in John 5:2)–which is approximately accurate if the Praetorium was at the site of the Hasmonean Palace/Church of Saint Sophia/ today’s Church of St. Mary of the Germans, and 2) the fact the site of the Antonia Fortress is right next to Bethesda shows it could not have been considered the Praetorium by the earliest Christians.

-A source from c. A.D. 525 known as “Brevarius A” states the Church of Saint Sophia contained the chamber where Christ was stripped and scourged. The Madaba Map from A.D. 560 shows a church northeast of the Sancta Maria Nea Church (see below for more details) with what appears to be a two-armed, black judgement throne in its middle. It was documented by Antiochus Strategos that the Sancta Sophia Church was destroyed when the Sasanian Persians sacked Jerusalem in A.D. 614. According to Strategos, after the Persian conquest of Jerusalem, Christians discovered 477 people dead inside the church. Remains of this church were later repurposed by the Muslims of the Rashidun Caliphate for palaces after they conquered Jerusalem in around A.D. 638. After the Muslim conquest, according to archaeologist Fr. Bargil Pixner, “It seems indeed that the area [where Sancta Sophia stood, just west of the Temple Platform’s southwest corner,] was settled by Muslims and therefore out of bounds for Christian services” (2010, 310-311). Nevertheless, “the Praetorium” is still remembered and clergy still resided there according to the Commematorium from approximately A.D. 808. After this point, pilgrim accounts before the Crusades no longer mention the Praetorium or church there.

-In 1914, during the excavations undertaken for the construction of a new hospital in the Jewish Quarter on the western side of the Tyropoeon Valley opposite the Wailing Wall, Louis-Hugues (L.H.) Vincent discovered “a fairly large quantity of dislocated human bones, mixed with some Byzantine debris. Lower down…a thick bed of ash covered a concrete floor” (Vincent, “Jérusalem. Glanures Archéologiques.” Revue Biblique Nouvelle Série 11, no. 3 (July 1914), 433). Vincent also discovered the supporting substructures of a building he believed was the Emperor Justinian’s magnificent “New Church of the Mother of God,” also known as the “Sancta Maria Nea” basilica. It seems likely the human remains were those of the 477 men and women Antiochus Strategos says were killed in the Santa Sophia during the Persian sack of Jerusalem in A.D. 614, with the substructures being supports–which Vincent dates to the time of Herod the Great–for the Hasmonean Palace (Vincent 1914, 434). The remains of the Sancta Maria Nea were discovered by Nahman Avigad in 1976 further to the west of the remains discovered by Vincent. This properly reflects the position of the Nea church along the Jerusalem Cardo (the main north-south street in ancient Roman cities) in the Madaba Map. The church on the map which appears to show a “judgement throne” in its center and what is believed to be the Sancta Sophia/Praetorium Church is to the northeast of the Nea.

-Very ancient pilgrim reports document the Sancta Sophia was near the Sancta Maria Nea Basilica and, therefore, likely in a location the Hasmonean Palace would have stood. No early sources or traditions before the Crusades mention, nor early churches marked, the locations of Herod’s Upper Palace or the Antonia Fortress as venerable locations of the Lord’s Passion.

-According to Dr. Denys Pringle’s The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A Corpus, Volume 3 The City of Jerusalem, in the year 1127 after the First Crusade, a religious-minded German who had settled in Jerusalem with his wife established a hospital for German visitors to the city who were unfamiliar with French, the current language of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. This man also built a church complex beside it dedicated to St. Mary (Pringle 2007, 228). This church became known as the Church of St. Mary of the Germans and was built over the area where the Sancta Sophia (and the remains of Pilate’s Praetorium) likely stood. Unfortunately, according to Pixner, in thorough German fashion the German crusaders cleared away all ruins down to the bedrock to build their church, hospital, hospice, and ceremonial hall. The remains of these buildings can still be seen to this day in modern Jerusalem. (Pixner 2010, 275).

-In the 1970s, the famous Israeli Archaeologist Nahman Avigad discovered the remains of upper-class buildings and residences from the 1st Century A.D. adjacent to the site of the St. Mary of the Germans complex. One of the residences immediately south of the Church of St. Mary of the Germans was especially luxurious. Father Pixner felt this residence, called the “Palatial Mansion” by Avigad, was a section of the Hasmonean Palace complex. There is good cause to think the Palatial Mansion could have been the living quarters of the Hasmonean Palace used by the Hasmoneans and Herod the Great (before he moved to his Upper Palace). Just north of the living quarters likely would have been the Praetorium/Court House (perhaps at one time attached to the mansion?) with a large plaza (i.e. “Stone Pavement” from John 19:13) where sentences could have been passed in front of the crowds.

For these reasons, I believe our Lord’s trial before Pilate, His scourging, and where He received His cross to begin His tortuous march to Golgotha, all happened on the western ridge of the Tyropoeon Valley overlooking the Temple at the former Hasmonean Palace–today the site of Church of St. Mary of the Germans Complex. (GPS Coordinates: 31°46’31.87″N, 35°13’58.58″E)

…

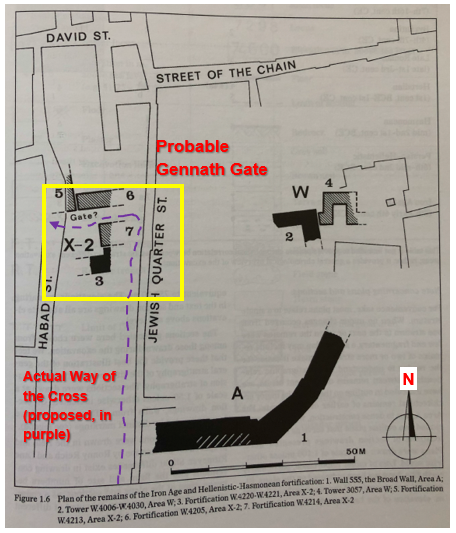

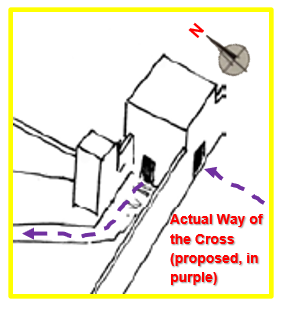

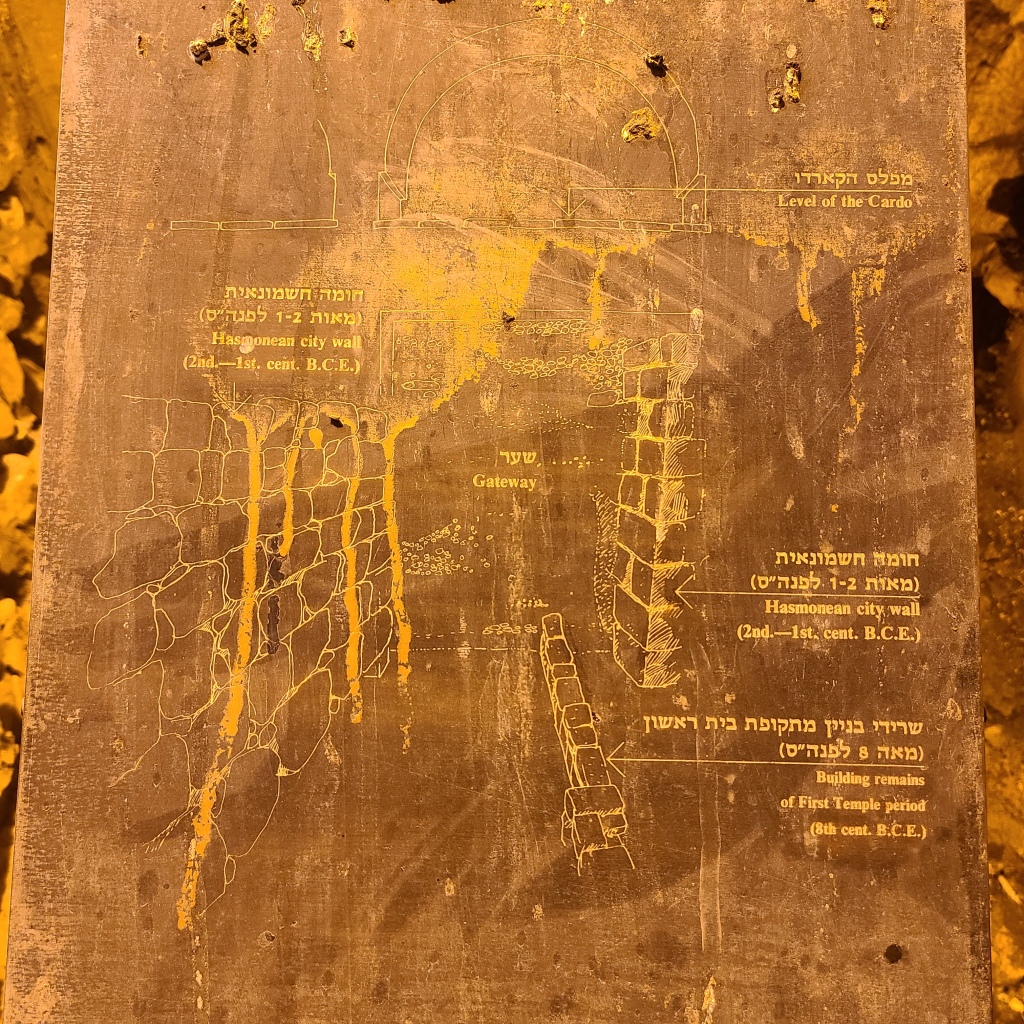

Another landmark along our Lord’s probable Way of the Cross was discovered by Dr. Avigad in from 1976 – 1978. His team discovered the remains of a Hasmonean-era city gate, dating from the Second Half of the 2d Century B.C. to the early 1st Century B.C., near the center of today’s Old City Jerusalem (Geva 2000, 206). It appears this gate is the “Gennath Gate,” a city gate of Jerusalem which Josephus identifies in his writings for the 1st Century (See Wars of the Jews 5.146). According to Professor Justin Kelley in his book The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Text and Archaeology, “the term [Gennath] is a Greek rendering of the Aramaic gantha, ‘garden.’” (Kelley 2019, 72). In his 1996 book With Jesus in Jerusalem, Pixner states the gate was probably known as the “Garden Gate” because Herod the Great had probably made a type of “city park” outside the gate here (139). That this city gate is not far from Golgotha, corroborates what we read in the Gospels about the area of Jesus’s tomb, which was in the same place as Golgotha. John 19: 41 states: “In the place where he was crucified there was a garden. In the garden, there was a newly hewn tomb, in which no one had yet been placed.” It is therefore likely our Lord would have processed northwards through the Gennath Gate on the road to Calvary.

Below is a map of excavation area X-2 where the likely Gennath Gate (highlighted using a yellow box, as in Image 8 above) was discovered. The Hasmonean remains of the gate are indicated as wall segments 5 through 7. Jesus would have exited the city of Jerusalem traveling between segments 6 and 7 westward (left). He would have then rounded the corner of what appears to have been a tower along the city wall—segment 5 appears to have been a part of this tower. As the Lord rounded the corner of this tower northwards, the dreadful, but life-saving place of Golgotha would have first come into His view. It’s truly awe-inspiring to think about…

If you, my readers, know of any additional substantial evidence either corroborating or challenging my argument on this topic (i.e. that the Praetorium was actually at the site of the Hasmonean Palace and today’s site of the Church of St. Mary of the Germans), I would very much appreciate hearing from you–please send me an email at zistezesto@gmail.com to let me know what you found. Thanks!

…

Now, getting back to my journey:

I walked westward across the Tyropoeon Valley and saw the Western Wall in the distance. I noticed there was some kind of construction going on along the western side of the valley…could the workers be finding pieces of the Church of St. Sophia? Of the actual Praetorium? I’m not sure if I’ll ever know.

I climbed up the valley and walked through the quiet, narrow streets of the Jewish Quarter. Multi-floor stone homes were everywhere I looked—some shady trees were allowed to grow which provided a respite from the desert heat. Small Jewish children in traditional clothes and hairstyles ran around. It was very peaceful. As I walked closer to the site of the St. Mary of the Germans complex—the likely approximate site of Pilate’s Praetorium, I ironically began to see spolia (pieces of ancient structures) on display outside of people’s houses. If only I could know what structures they actually came from! Lol.

I finally came to the site of the St. Mary of the Germans complex.

Unfortunately, the entrance into the remains of the church was locked and visitors could not get in. No matter, I continued to walk around the structure and through the immediate neighborhood. As I walked, I imagined the sound of the whips striking Christ’s back in this very place. I was able to walk up a couple balconies that gave a sense of the elevation (“Gabbatha”) of this location. The view of the Tyropoenon Valley, the Temple Mount, and the Mount of Olives beyond it were indeed spectacular. This place was definitely in an elevated position. The Hasmonean Palace here would have indeed provided a spectacular view of goings-on in the Temple (ref. the account of King Herod Agrippa’s nosiness I brought up earlier in this post, found in Antiquities of the Jews 20.189-190).

After walking a bit north of the site of St. Mary of the Germans, I eventually turned around and walked back south. As I walked, I noticed a lower road that allowed me to walk into the space of one of the lower facilities of the St. Mary of the Germans complex: its hospital (see photo below). The space was made into a small common area/park with a bench. I was getting hungry at this point and thought it would be good to have some lunch, so I took out a tuna kit and began eating. It felt good to put some food in my stomach. While I sat and ate, I meditated on what this place must have looked like in Jesus’s time. Brevarius A, an ancient text from around A.D. 525 describes the church of Pilate’s Praetorium and the chamber there where Christ was stripped and scourged. The Brevarius says “You go to the house of Pilate, where he had the Lord scourged and handed Him over to the Jews. There is a large basilica there, and in it the chamber where they stripped Him and He was scourged. It is called Holy Wisdom” (Wilkinson 2002, 121). I was amazed to think the actual chamber where our Lord Jesus was scourged could have in reality been just a few feet away from me, or where I was sitting just then.

After some quiet reflection, I got back up and walked back to the front of the St. Mary of the Germans Complex. I now intended–for the first time–to actually retrace some of the historical/actual Way of the Cross. The roads of the 1st Century, like the one discovered by Dr. Avigad, would have stretched some distance below the modern street level in Jerusalem. (In fact, stretches of the one discovered by Avigad that weren’t excavated probably still lie underneath some of the modern buildings!) Additionally, the system of modern roads doesn’t exactly mirror how the road system would have looked in the 1st Century. However, despite these unavoidable limitations, one can still take modern streets that closely trace the same route to Golgotha as our Lord. It is an absolutely surreal experience.

The streets were very busy as I began the approximately 500 meter walk from the site of the Praetorium (at St Mary of the Germans) to the Rock of Golgotha inside the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. As I wound my way westward along the true Via Dolorosa, I observed it was quite a different view than what Jesus would have seen—Jewish people using ATMs, ordering cheeseburgers, and sipping on iced coffee flurried about me. Eventually, I arrived in Hurva Square—a large open area in the Jewish Quarter with a large, famous synagogue. As I kept walking west through the north end of the square, I happened upon another important site I had been anxious to see.

In front of a small café are 9 large paving stones that stick out from the smaller, smoother paving stones all around them. Although the stretch of road built by Herod the Great and discovered by Dr. Avigad was dismantled so they could study the structures beneath it, according to Leen & Kathleen Ritmeyer in their book Jerusalem in the Year 30 A.D., these 9 stones were saved and incorporated into the modern pavement 10 to 15 meters away from where they had laid in the 1st Century! (2015, 36). Jesus Christ Himself, Lord of Lord and King of Kings, may have stepped across these very stones as He carried His cross. These stones are in plain sight and yet few if any people realize their significance! (GPS Coordinates: 31°46’31.59″N, 35°13’53.96″E)

Furthermore…something else about where these stones are located today is worth mentioning…

I have been blessed to have explored many places that history/archaeology or tradition have indicated were the site where someone holy was, or something holy happened. The importance of many of these places is not perceptible to most. And, even then, the information that guides me can only take me so far when determining the exact locations–I was not an in-person witness to events from thousands of years ago and security cameras have only been around since 1949! However, while on my pilgrimages (and as documented in my blog posts), I occasionally notice little things which seem to indicate I’m at the correct place–possibly God giving me a “little hint” so I can, in turn, share with you, my readers.

The stones from the road of Herod the Great are (unfortunately) not a tourist attraction or pilgrimage destination. There isn’t even a sign posted that tells you what they are and where they’re from!–I only found out by reading Leen and Kathleen Ritmeyer’s book mentioned above. Given these stones are tragically inconspicuous, and given a very limited probability that people–including the café owners–would associate them with the road our God took to the cross (especially being in the Jewish Quarter!): divine inspiration and a divine sense of humor can be the only explanation for how the café adjacent these probably sacred stones got its name…

Of any name to pick, “Holy Café” somehow must have just seemed the right pick to the owners! Haha! Incredible!

I kept walking westward and eventually came to the remains of the ancient Byzantine Cardo road. A “cardo” in ancient times was the main north/south road that went through a city. This road was discovered during excavations. Although this road itself does not date from Jesus’s time but to the A.D. 500s, a 1st Century road would have stretched along this same path, the remains of which are probably still buried some distance below the surface. This road would have been the main commercial avenue of Jerusalem for hundreds of years, lined by columns and people selling their goods.

A painting next to the Byzantine Cardo today shows what it would have looked like in ancient times…very cool!

I took a right onto the Byzantine Cardo and began walking northwards. As I kept walking, I stumbled upon a site on my left I did not anticipate to see.

In fact, I thought it had been reburied after being excavated–the remains of excavation area X-2…the site of the remains of the Gennath Gate! (GPS Coordinates: 31°46’35.31″N, 35°13’51.68″E) Again, this is a site that is not well advertised, it is not a major tourist attraction. However, it is probable that our Lord walked through this very gate (as shown in Images 8 and 10-14 above) to exit Jerusalem and carry His cross to Golgotha.

The pictures below show the remains of the gateway that were excavated. Tragically, the archaeologists have not dug more of the gate out, but I imagine it could undermine the stability of the modern shops and homes above.

It all makes me wonder what it must have looked and sounded like as Jesus came through this very gate. I’m sure the noise of the great multitude following Him, the soldiers yelling at Him, and crowds of pilgrims working to bring Passover lambs through the same gate and to the Temple for sacrifice must have been deafening.

After reflecting at this special gate, I continued to move onwards, closer to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (where I had just been for Mass earlier that very day!). The streets were bustling with people walking and salespeople selling their wares, drinking tea, and using their smartphones.

I eventually took a left westwards again towards Golgotha and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

To follow the actual Way of the Cross using the modern roads in the Old City of Jerusalem (see map below), start at the ruins of the Church of St. Mary of the Germans (also known as the “German Hospice”), then take Tif’eret Israel Road west to Ha’hurva Square. Once in the square, keep walking west, bearing slightly to the south until you reach Ha’rova Warriors 1948 Road (north of the Hurva Synagogue) and then continue westward on that road. You will eventually reach a set of stairs that lead down to the Cardo Road (this is the modern road along the ancient Byzantine Cardo, there was likely a road here in the 1st Century as well), go down the stairs onto the Cardo Road and start walking north. Follow this road (you should eventually see the ruins of the Gennath Gate in an open-air underground viewing area on your left) until you reach David Road/Suq al-Bazar Road and take a left onto that road (to go west). Not far down this road, you will take a right onto Suq al-Lahhamin Road (to go north). Follow this road until you reach Suq al-Dabbagha Road and take a left onto this road (to go west) until you come to the entrance square in front of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (which is built over Golgotha and Christ’s tomb) on your right.

As I walked down the road towards the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, I noticed an open doorway into a church complex on my right. I had read about this place! It was the Russian Orthodox Church and Hospice of St. Alexander Nevsky (GPS Coordinates to entrance: 31°46’41.01″N, 35°13’50.45″E). It felt a little odd going into a Russian church, but the Russian Orthodox nuns seemed nice enough, so I went inside to look at some of the amazing historical remains I knew were preserved inside this church.

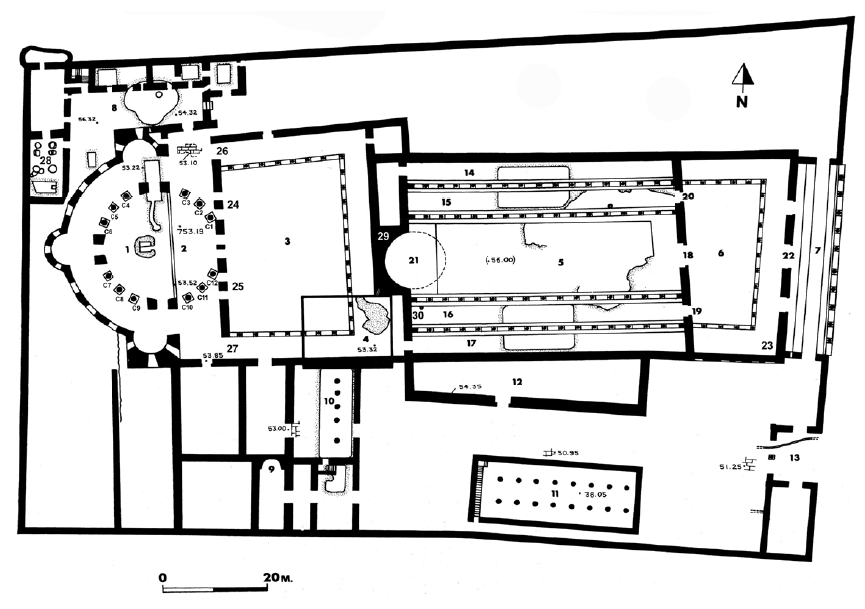

When the first version of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher was finished by the Roman Emperor Constantine in A.D. 335, it was much larger than the current structure today, and it stretched further east to the “Cardo” road I mentioned earlier. Excavators of the Russian property in the late 1800s discovered an archway and walls made of large stones that made up parts of the entrance to this earliest Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Per Kelley, the archway appears to be a part of a small guardroom (2019, 99). The walls with the large stones are thought to be the southeast corner of Constantine’s church along with its southernmost (of three) entrances. Some also think the arch and the walls may date even earlier and could have been used as a part of the pagan temple complex the Roman Emperor Hadrian had built over Golgotha and Christ’s tomb to deter veneration of those places.

Below is the floor plan of the Constantinian/Byzantine Church of the Holy Sepulcher from Kelley (2019, 98). The gray rock near the middle of the floor plan is Golgotha (#4), further to the left, towards the middle of the circle of columns is Christ’s tomb (#1).

Below is the ancient archway inside the Russian Hospice. Immediately on the other side is the guardroom (#13) in the image above.

Further north of the archway were the walls made of large stones that made up parts of the entrance to Constantine’s earliest Church of the Holy Sepulcher (see Image 44 below). The modern stairs (which are replacing the ancient stone stairs which are no longer present) lead through the southernmost of three entrances into the grand former basilica.

Below is a photo of the southernmost entrance into the basilica. For nearly seven hundred years, from A.D. 335 to A.D. 1009 (when the first church was destroyed by a Muslim ruler), countless pilgrims to this holy place would have streamed through this entrance to see the Rock of Golgotha and the Tomb of Christ.

Next to the ancient wall, the Russians set up a Crucifixion shrine which uses a detached piece of the actual rock of Golgotha. The guidebook provided to visitors at the entrance says the Russians purchased it “for a considerable sum”—I bet! Haha.

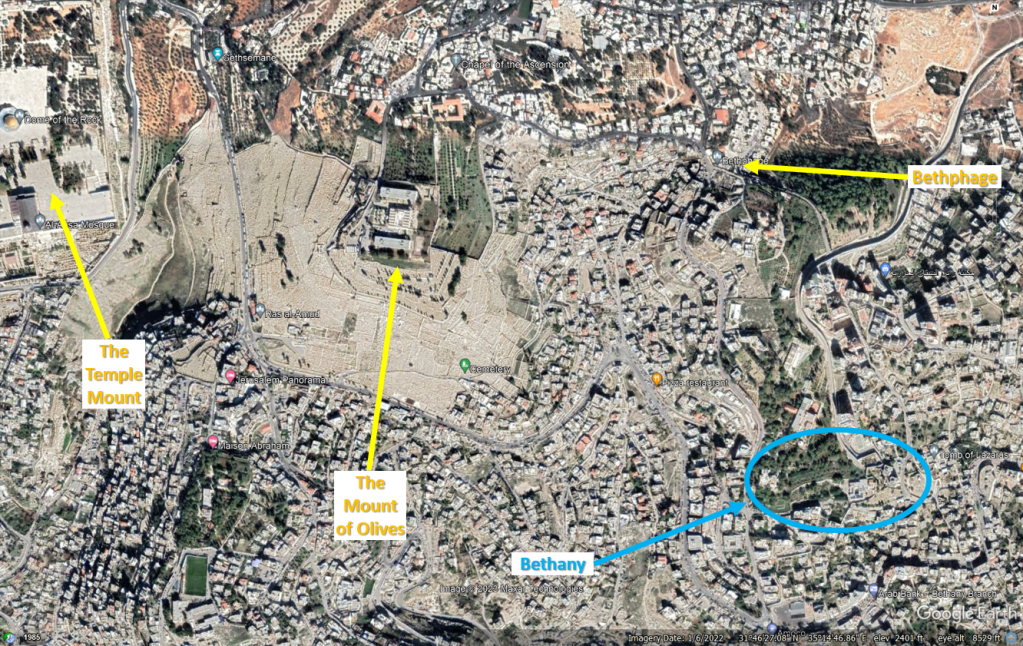

As I walked out of the Russian church, I knew that my time was short to make it to an appointment I had set for myself a couple months in advance. The place I was going was over a “Sabbath Day’s Journey” away (ref. Acts 1:12), on the other side of the Mount of Olives: the ancient town of Bethany from the New Testament–home of Sts. Martha, Mary, and Lazarus, the friends of Jesus.

The town of Bethany appears several times in the Gospels, and it appears Jesus enjoyed visiting there during His ministry. It was here Jesus taught the sisters the importance of listening to Him and not being distracted by the anxieties of the world (Luke 10:38-42). It was here in the house of Simon the Leper the sister Mary anointed Jesus’s feet and dried them with her hair (John 12:1-11). Matthew 21:17 and Mark 11:11-12 also mention Jesus lodged in Bethany during Holy Week. The Wikipedia article about Bethany actually has a very good, detailed analysis about the meaning behind the name “Bethany.” St. Jerome and modern scholars believe it means “House of Affliction” or “House of the Poor.” According to the article, these meanings indicate the town may have been the site of an almshouse and a center for caring for the sick, poor, and pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem. The article mentions this concept may be corroborated by the interaction between Judas and Jesus after Mary used costly oil to anoint Jesus’s feet in John 12:4-8 (Pakaluk 2021):

“4 Then says Judas Iscariot, one of his disciples, the man who was about to betray him: 5 ‘Why wasn’t this oil sold—for three hundred denarii!—and given to the poor?’ 6 He said this, not because he had any concern for the poor, but because he was a thief. As the keeper of the money box, he took the contributions for himself. 7 ‘You leave her alone,’ Jesus said, ‘so she can keep it, for the day of my burial. 8 The poor, always, you all have with you, but me you do not always have.’”

That Judas specifically has the poor on his mind and mentions the poor (although not in an altruistic way), and that Jesus says “The poor, always, you all have with you” may be an indicator of Bethany’s role as a village dedicated for caring for the disadvantaged.

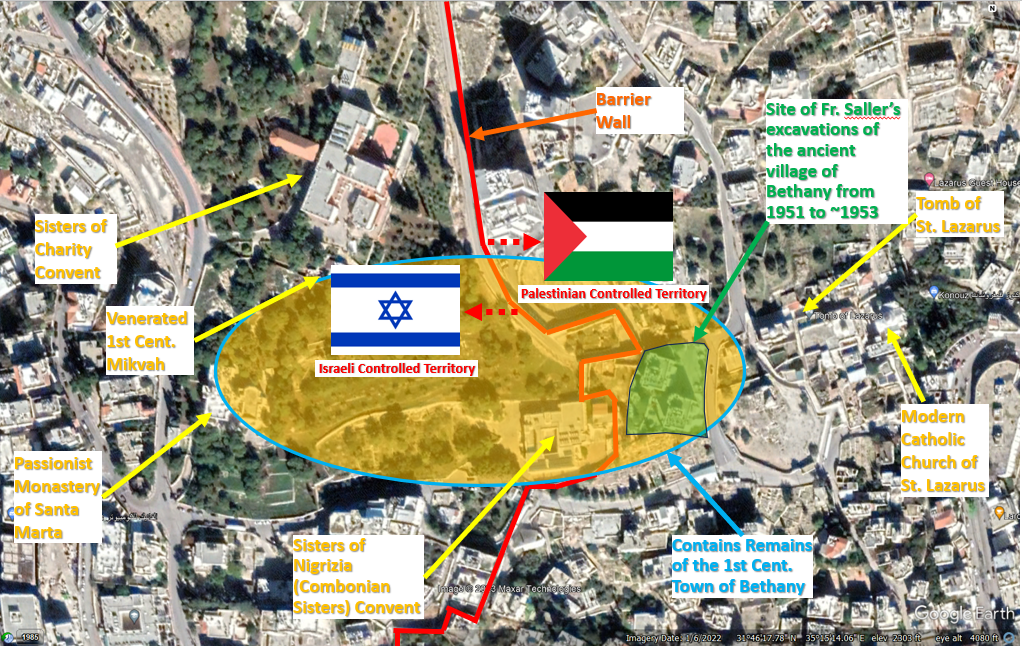

The situation of the ancient town of Bethany today (Found around these GPS Coordinates: 31°46’16.88″N, 35°15’14.92″E) is interesting–to say the least. The Tomb of Lazarus where Jesus raised him from the dead has been a place of veneration continuously since the early years of Christianity and is mentioned frequently in ancient pilgrim accounts. The 1st Century town of Bethany was eventually buried over the centuries, but was re-discovered just to the west of the Lazarus’s Tomb during excavations by Father Sylvester J. Saller, O.F.M. from 1949 to 1953.

At the time of Father Saller’s excavations, several Catholic religious congregations owned property comprising ancient Bethany, including the Passionists and the Sisters of Charity. Later, the Sisters of Nigrizia (also known as the Combonian Sisters) would also take ownership of some land comprising ancient Bethany.

Starting in 1994, after a spate of Palestinian terrorist attacks in Israel, the Israeli Government began constructing a barrier wall separating Israelis from Palestinians. After a large Palestinian uprising against Israel known as the “Second Intifada” began in September 2000, the Israeli Government moved to accelerate construction of a permanent barrier wall separating the West Bank (where most Palestinians live) from Israel. Most importantly, the wall helped decrease Palestinian terror attacks inside Israel, but unfortunately its path cut the site of ancient Bethany in two as it remains today! (see Image 52 below)

A portion of the site of the 1st Century village of Bethany (including the area specifically excavated by Father Saller), Lazarus’s Tomb, and the modern Catholic Church built over the site of a series of ancient churches, are all on the Palestinian side of the barrier wall within the West Bank. The other portion of the site of the 1st Century village of Bethany is on the Israeli side. According to Gerhard Kroll in his seminal work Auf Den Spuren Jesu: Sein Leben – Sein Wirken – Seine Zeit, the town of Bethany was not large and was bound by graves on the western edge of the Passionist property, graves near the southern edge of the Combonian Sisters’ property, and Lazarus’s grave on the east (2002, 279). Based on archaeological finds, Father Saller mentions in his work Excavations at Bethany (1949 – 1953) it is “probable that a village stood on the lands now owned by the Passionists more or less continuously ever since the Bronze Age” (1957, 354).

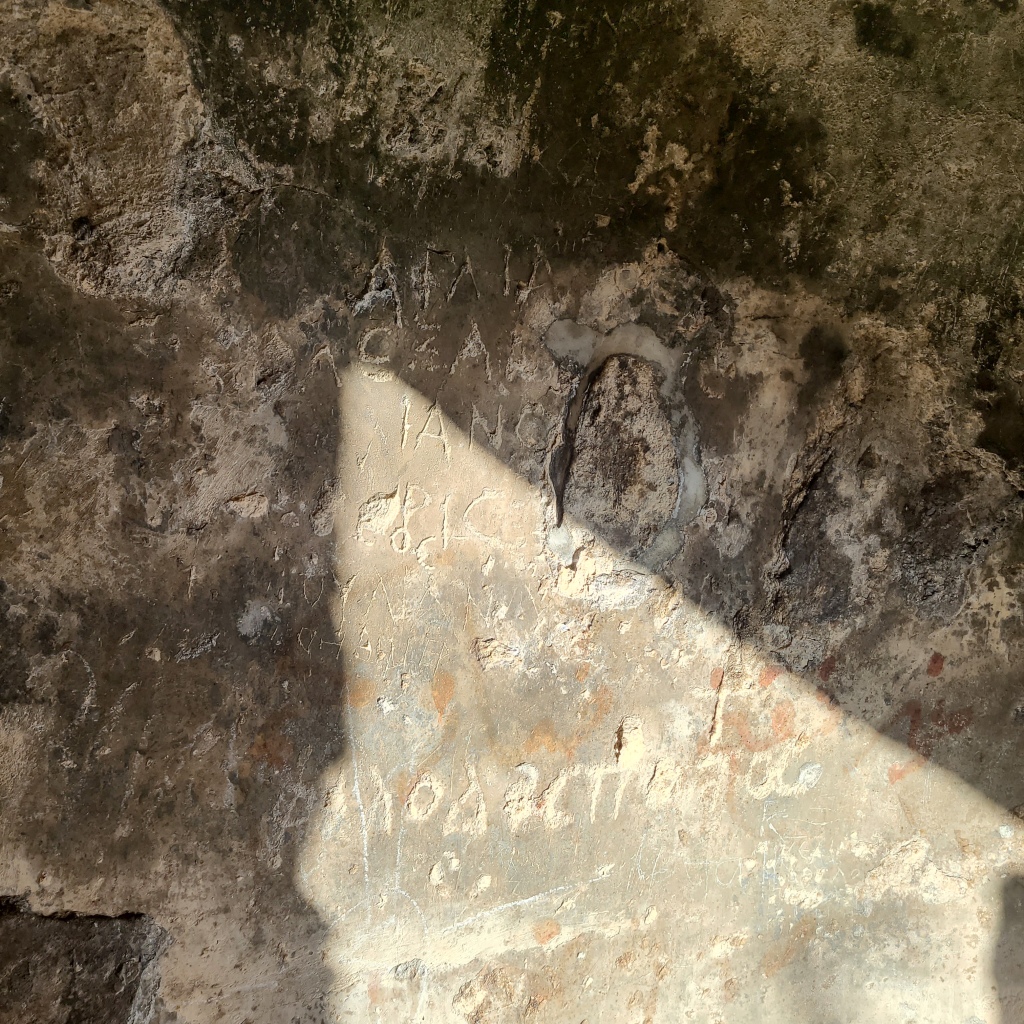

When I read more about the old town of Bethany during my research prior to my trip, I found out about a special site in the garden of the Sisters of Charity convent. This garden contains an ancient mikvah with pilgrim graffiti dating to the 4th Century (a Mikvah is a pool of natural water in which Jews bathed for the restoration of ritual purity). That the mikvah was a pilgrimage location, indicates there may have been an ancient tradition it was used by the Lord and His disciples! I Googled “Passionists Bethany” and was able to find a great article about the Passionist Monastery at Bethany written by a Passionist priest. Thankfully, the priest had an email address posted on his website, so I asked him if he knew someone I could contact at Bethany’s Passionist monastery. He graciously responded back and gave me the email address of the local superior of the Passionist “Monastery of Santa Marta” (St. Martha) at Bethany: a priest I’ll refer to as “Father R.” It so happens Father. R. is also the pastor for the Sisters of Charity and the Combonian Sisters, so he would be able to help me visit those properties/areas as well. I sent an email to Father R., respectfully asking if I might be able to visit his monastery; the area of the ancient village of Bethany across the properties of the Passionists, Sisters of Charity, and Combonian Sisters; and the venerated mikvah. Father R. responded back to me and said he would be happy to meet me and show me around at 3PM on my last full day in Jerusalem. I was ecstatic–what a blessing to be able to visit the same place where our Lord took refuge when visiting Jerusalem!

…

Once again, getting back to my journey:

I stepped out of the Russian church and saw it was 2:16PM. I had to go 2 miles to Bethany and decided I probably should run there to make sure I was there on time. I started running through the streets of Jerusalem. Thankfully, this part was flat! I eventually reached the Western Wall Plaza and ran south outside the walls of the Old City and then northeast towards the Kidron Valley and Gethsemane. The Kidron valley is pretty steep, so it felt good to go down hill. Once I reached Gethsemane at the foot of the Mount of Olives, then the real workout began!…Bethany is southeast of the Old City and in order to get there, I would need to run up and over the Mount of Olives! It was hot out and not super comfortable, but I made it happen! Luckily once I made it to the top, there was another downhill portion that took me into a valley. At this point, Google Maps tried to take me on at least one road that was blocked! I ended up having to make my own way up the side of another steep hill that was densely packed with Middle Eastern houses. I finally found my way to another main road around the hill and took it down towards the entrance to the Santa Marta Monastery! At last! Despite getting turned around, I made it with 4 minutes to spare: 2:56PM! God is good!

I was before the large vehicle gate of the monastery and pushed the intercom button. The gate opened and I walked in. Father R. came outside of the monastery and greeted me. It was great to meet him in person! He took me inside to the monastery cafeteria and sat me down. He went into the kitchen and got me some DELICIOUS watermelon and cool water. It all tasted fantastic and was a very kind and welcome gesture. After talking to him a little more and about his monastery, we stepped outside to see Bethany! He took me first to the venerated mikvah north of his monastery and on the property of the Sisters of Charity. It was incredible to finally see the mikvah in person. I had read about it and saw pictures, but now I finally got to see where it was exactly so I could annotate its exact GPS coordinates in my book, The Second Person of the Trinity in Time and Space.

It was powerful to think of Jesus, the Apostles, and the disciples of Bethany potentially using this mikvah. What brought it even more to life for me was actually stepping down into the mikvah itself and looking at the ancient pilgrim graffiti from the Byzantine period etched into the walls.

After viewing the mikvah, Father walked me all around the premises of his monastery and the convent of the Combonian Sisters.

Ancient caves were scattered across this small parcel of land, no doubt used by residents for different purposes throughout the town’s long history.

As we wove our way amongst groves of lush trees (especially olive trees!) through the site of ancient 1st Century Bethany, I couldn’t help but wonder if I was walking over the site of what once was the house of Sts. Mary, Martha, and Lazarus–which has not been definitively discovered (if even possible to determine). As we walked westward, the tall barrier wall bisecting Bethany came more closely into view. I could even see one of the silver domes of the Greek Orthodox Church of Lazarus (see photo below), adjacent to Lazarus’s Tomb on the opposite side of the wall. I hope I can visit Lazarus’s Tomb someday!

Father R. even took me to a small parcel of land that the Passionists own that is right next to the West Bank Barrier Wall. It appeared that some kind of excavations had taken place here, at one point, but the area was largely overgrown with scrub bushes and grass. Despite this, the earth was “honeycombed” with more cisterns, caves, and mikvahs–amazing. As we walked, Father R. told me he had considered looking into allowing archaeological excavations here, but he also wanted to balance this with maintaining a peaceful atmosphere and the site’s natural beauty for pilgrims. A challenging choice indeed.

Father also discussed with me all of the initiatives he and his fellow priest, who I’ll call “Father M.,” had begun since being assigned to Bethany. They had spent a lot of time cleaning the grounds and landscaping. He also told me they intended to make chapels or even guest rooms out of some of the caves there! It was inspiring to see such a dynamic team of priests working to honor Christ by honoring the memory of the special holy place they had been entrusted to oversee. Like the Family of Bethany–Sts. Lazarus, Mary, and Martha–these priests are working hard to continue the 2,000 year old tradition of Bethany being a place known for showing hospitality to travelers and those in need.

After exploring the site of Ancient Bethany, we made our way back to the patio in the back of the Monastery where Father M. was waiting for us. The priests told me they were expecting some guests for dinner and asked me if I wanted to stay with them. I told them I’d be honored! As we waited for everyone to show up, we all sat down on some wooden patio furniture, cracked open some beers, and talked as the sun got low in the sky. The evening became beautiful and cool. I couldn’t believe I was relaxing among olive trees and ancient caves and sharing fellowship with fellow disciples–priests nonetheless!– in the same place where Jesus had done the same when He was on earth.

Then, the guests began to arrive! In addition to caring for the spiritual needs of the religious congregations at Bethany and maintaining the monastery, Father R. and Father M. were responsible for caring for Filipino Catholics within the Jerusalem area. They care for their spiritual needs and welcome in any disadvantaged to stay at the monastery.

The guests consisted of about 7 Filipino women and 3 Filipino men and they started bringing in and preparing Filipino barbecue, stir-fry, cooked corn, and fish! After about 30 minutes or so, we had a feast with superb Filipino cuisine! Everyone was talking, laughing, and having a great time. It was impossible not to smile–everyone’s joy was infectious. It was very cool to get to know everyone, and I could tell they loved and appreciated their priests so much. After Father R. blessed the food, everyone served themselves and sat in a circle around the food table and talked as we enjoyed the cool night. I came back for more food once or twice…it was so good! We talked about current events and compared and contrasted Filipino and American cultures…I learned a lot and it was a lot of fun. Although I was the only non-Filipino there, I felt perfectly welcome. They were all so very kind, lively, and happy. At the end of the night, I thanked them for letting me share the meal with them and remarked that, like Jesus, I was blessed to have found my own “Family of Bethany” in the same place with all of them. My short time in Bethany was an experience I will take with me the rest of my life and always cherish. Thanks again so much to Father R., Father M., and their congregation for their generous hospitality!

After dinner, Father R. graciously gave me a ride back to my hotel on the other side of Jerusalem’s Old City. I rested well that night, and woke up early to drive to Tel Aviv and start flying back home.

My layover was Istanbul Airport, and I had an incredible view of the city and the Bosporus Strait as we made our approach….

It had been an incredible pilgrimage. Thanks be to God for a safe and successful trip. Thanks to you, my readers, for allowing me to share this adventure and my research with you (A special thanks also to my Father-in-Law, Tom, for proofreading some of this post for me!).

I hope that bringing you this information will help bring us all closer to Christ and help us all better appreciate the historicity of the Holy Sites of our faith–both known and little-known.

Also, if you enjoyed this post and want to learn more, check out my one-of-a-kind book, The Second Person of the Trinity in Time and Space: What is Known Historically About Jesus and the Holy Sites of the New Testament, sold on Amazon.com! (click below)