For adult audiences revisiting the now classic 1990 film Home Alone, Kevin McCallister has become synonymous with a privileged rich kid who does not care about anyone but himself. Mincing no words, one Vice article puts it this way: “Kevin is, at his heart, a spoiled, entitled, rich suburban brat who is willing to sacrifice his family’s home, and even commit murder, to avoid bringing his staycations or vacations to an end.” This argument feels ungenerous, as if it sidesteps purposefully the gentler, human elements of the film and its deeper spiritual messages as well.

After all, when I watched the first Home Alone movie as a child with my mom, I remember feeling drawn in by the moments of tenderness that Kevin shares with his mother more than any other part. I assumed that Kevin seemed callous at points because he was lonely and mistreated. My family was not one that could ever dream of a Disney vacation, much less a family trip to Paris. Yet, I never felt jealous of Kevin’s large, glitzy house or fancy holidays abroad. Instead, I commiserated with his loneliness. Even as a part of a bustling family, Kevin McCallister is forgotten in more ways than simply being left physically home alone.

Similar to the McCallister family (words I never thought I’d write), my family growing up, and my family today for that matter, is not immune from speaking unkind words toward each other. In one of the most memorable parts of the film—the one when the eight-year-old boy wakes up in the house alone and discovers his family has accidentally left him out of their vacation—Kevin expresses momentarily gleefulness. He recalls in his head a litany of abusive phrases his family has hurled at him, including one from his Uncle Frank dubbing him a “little jerk.” Similarly, he remembers his older sister Megan referring to him as “completely helpless!” His brother Buzz menacingly pops in his head as well, threatening him. “I’m going to feed you to my tarantula,” Buzz jeers.

Even Kevin’s mom, Kate, is not depicted as an idyllic Marian figure. Kevin replays words she said to him in anger: “There are fifteen people in this house,” she remarks accusingly, “and you’re the only one who has to make trouble!” Once he wakes up alone without anyone else in the house, Kevin’s troubles seem to be alleviated, at least momentarily. Viewers might remember at this point in the film that the music becomes merry. Kevin brushes his teeth and belts out a jazzy rendition of “White Christmas” by the Drifters, using a comb as a microphone. The voice he sings over is much deeper than that of an eight-year-old, and we see Kevin acting as an adult for the first time in the film. For Kevin, adulthood translates into being in control of not only the house but also his emotions.

When I rewatched this film this year and last with my children—they are ages eight and nine—they laughed at Kevin’s antics and “pranks” as they called them, yet they also wondered a little at whether he was acting admirably. “Would I get in trouble if I did this?” my daughter asked me this year, as she saw Kevin booby-trapping his door. She instinctively felt that what he was doing was wrong on some level. Yet Kevin, in a child’s way, was confronting a very real evil that threatened his safety. The answer about his morality is not an obvious, or easy one. Like I had as a child, both of my children noticed how unkind Kevin’s family was to him, and it seemed to make sense to them that he would, in some ways, transfer his unhappiness about his family life to his treatment of the criminals in the film, directing his internal rage to these external bad guys. In a psychological vein, Kevin’s prankish behavior can be interpreted as a defense mechanism, a cry for attention to regain control in a life that seemingly feels chaotic and hurtful.

Lest you think I am being too generous or reading too much into Kevin’s psychological state, I bring your attention to the moments in the film that I was drawn to as an adult this time, moments that I glossed over as a child, drawn in during the past as my children were recently by the criminals’ tripping over ice sheets and the singeing of receding hairlines. As a mother revisiting this film, I observed the moments and places where Kevin discovered comfort within his family. As a Catholic convert revisiting it, I discerned the instances and locations where Kevin sought solace beyond his family, specifically finding spiritual reassurance at his local parish.

While a psychological reading of Kevin’s behavior might suggest the child is reacting to verbal abuse by doing anything to get attention and regain control of his life, a Catholic reading might suggest that Kevin is experiencing spiritual desolation. Desolation, in the context of St. Ignatius of Loyola’s teachings, is characterized by a sense of spiritual alienation and a feeling of being distant from God’s love. It entails being separated from our communities and drowning in our negative feelings—as Kevin is at the beginning of the film when he replays his family’s negative words about him. St. Ignatius describes desolation as a “darkness of soul, [a] disturbance in it, [and a] movement to things low and earthly.” Kevin’s treatment of the criminals is just that, “low and earthly.”

Yet Kevin seeks, and is moving toward, consolation, or spiritual solace and enrichment, throughout Home Alone. When the criminals, Harry and Marv, realize that Kevin recognizes them when they are staking out his neighborhood, they begin chasing him. And this is where the movie takes a spiritual turn that I see as the heartbeat of the film. Kevin runs toward that Catholic parish near his home. Just as he acted being an adult earlier in the movie, in this moment, he acts being a shepherd in a crèche, or nativity scene, outside the church. The criminals state that there is no way they are going in the church (“I’m not going in there!”) but, at this point, neither is Kevin.

Harry and Marv drive off, and the camera pans in on Kevin in this outside space, the parish doors close to him and spotlighted, but he does not enter. Kevin symbolically stays in a liminal spiritual place, outside of doors that would open for him if only dared enter them. With this said, it is not an accident that Kevin’s fear and loneliness lead him to a symbolic representation of the Incarnate God within the crèche. His soul is yearning for fulfillment, but he cannot appreciate or understand what he seeks. As soon as the criminals leave, he runs back toward his home, where he can remain King, not Christ, from whom he is now fleeing.

Back in his home, Kevin, for a while, finds the earthly dominion he seeks. He becomes a masterful orchestrator, embodying Michel Foucault’s classic theory of the panopticon. Foucault, in his Discipline and Punish provides a historical analysis spanning the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. He examines the evolution of criminal codes and punitive measures, illustrating the shift from corporeal forms of torture to the ostensibly milder approach of imprisonment during this time frame. Foucault contends that the cessation of torture was not a consequence of increased social progress; rather, it marked a novel method for individuals to exert control over both one another and their environments.

In the panopticon, a prison design dating back to the late eighteenth century, a single watchman can observe all inmates without their knowledge of whether they are the specific ones being watched. This design induces a pervasive sense of constant surveillance. Like the watchman, Kevin’s meticulous planning and execution of traps within his home establishes a power dynamic between him and the criminals he fears that is reminiscent of the panopticon. In the microcosmic fortress of his home, he assumes the role of the unseen human authority, imposing consequences on those who pose a threat to his lordly reign. Foucault relates, “He who is subjected to a field of visibility, and who knows it, assumes responsibility for the constraints of power.” In Kevin’s case, the criminals become the subjects of his imposed visibility, and the eight-year-old assumes the role of the wielder of power within his territory. Kevin’s dream is himself as both king and a self-assured, suburban adult, the two roles entwined in his mind. The dynamics shift through the course of the film, wherein Kevin transforms from a child at the mercy of his family’s unkindness to a mastermind orchestrating the consequences for those who have wronged him.

Ultimately, this exercise of power becomes a coping mechanism, a way for Kevin to reclaim agency in a world that has momentarily abandoned him. Just as the panopticon is a mechanism of discipline and power, Kevin’s traps become a means of control over his immediate surroundings. The intricate web of pranks, while appearing mischievous, reflects a deeper psychological need for autonomy and security, a manifestation of Kevin’s quest for solace and refuge in a realm where he can dictate the terms.

Importantly, as I mentioned at the beginning of this essay, Kevin in my estimation is not a spoiled rich kid who tortures others for fun. Instead, he is a hurt child, looking for God. And I believe he finds him. While the majority of the film focuses on Kevin’s relationship with the criminals, the heart of it focuses on his relationship with Marley, an elderly neighbor whom Kevin initially fears.

You might remember the name Marley from Charles Dickens’s 1843 A Christmas Carol. “Marley was dead: to begin with,” Dickens’s narrative about the meaning of Christmas opens. A former business partner of Scrooge, Marley serves as a cautionary specter, visiting Scrooge on Christmas Eve and reminding Scrooge that he will soon suffer a similar fate. Laden with heavy chains and money boxes, which symbolize a life consumed by greed and selfishness, Marley tells Scrooge that he will encounter three spirits and must heed their messages, or else, he, Scrooge, will be condemned in the afterlife to bear even weightier chains of his own greedy making. Scrooge has a decision to make: change his ways or lose his soul.

In the context of Kevin’s story, the name Marley carries spiritual weight. Kevin ought to listen to this old man, and he ought to contemplate whether he might suffer from a dismal fate, perhaps a fate like Marley who neighbors taunted, and, we later learn, whose family has abandoned him. Like Scrooge, Kevin at first dismisses and fears the Marley of this film. Kevin’s brother, Buzz, tells him that Marley is a serial killer called “the South Bend Shovel Slayer,”[1] when the two spot the man shoveling snow outside his home. Kevin believes Buzz, running away from Marley each time he sees him and acting as if he is a criminal just like Harry and Marv—only worse, it seems to him.

Yet at one of the film’s pivotal moments, when Kevin is afraid of the criminals coming to his house and believes he can do nothing to stop them, he finds Marley in an unexpected place and Marley acts unexpectedly. That night, Kevin had visited Santa Claus, or St. Nicholas, and he told him that all he wanted for Christmas was his family back. This “spoiled, rich kid” does not want toys. He does not want to be the head of his house, alone. He wants his family back—the ones who said terrible things about him.

Kevin then visits the Catholic church near his house, entering it while “O Holy Night” is being sung in the background. Like most eight-year-olds, he looks from one statue to the next, focusing on one of St. Francis of Assisi, who legendarily created the first Christmas crèche in 1223. “Fall on your knees,” we hear, “Christ is the Lord.” Kevin prays. Then, he is joined in his pew by Marley, who wishes him a “Merry Christmas.”

Kevin does not run from the old man this time. Instead, he confesses his sins. Marley tells him that everyone is “always welcome at church,” even those who have done bad things, as he suspects Kevin has throughout the year. Earlier, Marley had witnessed Kevin stealing a toothbrush from a convenience store, so Marley’s idea of Kevin is not baseless. Kevin explains that he has done numerous bad things throughout the year, but the worst is that he had wished ill will toward his family. Now, he recognizes that although they may not be perfect, he loves them—and should have treated them better.

At this point, Marley offers Kevin the most important advice within the movie, and what I read as the movie’s Christian moral: “Deep down, you’ll always love [your family]. But you can forget that you love them, and you can hurt them, and they can hurt you, and that’s not just because you’re young.” Kevin, here, is called to forgiveness, and I am reminded of what the Apostle Paul wrote to the Colossians, “Bear with each other and forgive one another if any of you has a grievance against someone. Forgive as the Lord forgave you” (3:13).

Although this moment may not precisely mirror the formal sacrament of reconciliation within the Catholic Church, given that Marley is not a priest, there is a palpable peace that permeates the encounter. The advice Marley imparts becomes a catalyst for Kevin’s journey toward forgiveness and spiritual consolation, echoing the Apostle Paul’s counsel to the Colossians. Likewise, Kevin counsels Marley, encouraging him to overcome his fear of talking to his estranged son, who has kept him away from his granddaughter now singing in the choir. Kevin fears honesty with his family in the same way Marley does with his family.

The Catechism, underscoring the concept of the Church as a “family of God,” refers to its parishioners as the “People of God.” In its deepest reality, the Church is not merely an organization or institution but a living family of God’s people united in Christ. The Catechism aptly states, “The Christian family is a communion of persons, a sign and image of the communion of the Father and the Son in the Holy Spirit. In the procreation and education of children, it reflects the Father’s work of creation.”

Kevin and Marley, through their shared vulnerability, form a bond resembling a parish family—one that mirrors the communion spoken of in the Catechism. This communion renews both of them, leading them toward reconciliation. In their connection, we witness the transformative power of vulnerability and shared struggles, echoing the communal essence of the Christian family. Before eating dinner that night, Kevin’s new sense of adulthood entails making the sign of the cross and praying before his meal. This is a far cry from making believe earlier in the film that he is shooting a pizza delivery boy and bragging that he has a whole cheese pizza to himself before he sits down to eat. While he still has much to learn, a sense of Kevin’s increasing move toward spiritual consolation is evident. He has a family of his own, but he also has a church family that includes Marley.

Adult viewers recalling the ending of Home Alone most likely remember Kevin as besting the criminals who break into his house. Yet, in the end, he does not. They grab him, poised to enact Hammurabi-style justice on him, hanging the boy on a hook on the back of a door and saying they plan to torture him physically. While Kevin may have conceived of his actions as pranks, the criminals are unbound by any enlightened principles of discipline and punishment. This critical juncture again echoes Foucault’s insights into the panopticon’s limitations. While Kevin’s traps and orchestrations within the microcosm of his home initially mirrored the panoptic power dynamic, the criminals’ unrestrained violence disrupts this paradigm. In the absence of structured discipline, the criminals embody a more primal form of justice, revealing the fragility of systems built solely on the concept of surveillance and control.

And here enters Marley, “the South Bend Shovel Slayer,” and part of Kevin’s Catholic church family. He takes his shovel and overcomes the criminals, saying these words to Kevin afterward: “Come on. Let’s get you home.” Kevin’s pilgrimage is over, and his playacting, his taking on the role of watchman and adult, could not save him. Marley saves him. Marley takes him home. He takes him to God. The days of discipline and punishment are over and have been disrupted. God’s saving grace changes the story. In this salvific act, Marley becomes the instrument leading Kevin not only to safety but also to a deeper understanding of himself as a child of Christ, culminating in the end of a spiritual journey with redemption and grace.

When Kevin’s mother finally arrives home the next morning, the first thing she says to him as she looks into his worried face is, “I’m sorry.” He runs into her arms, and his story of forgiveness feels complete. No family may ever be perfect, as Kevin discovers during his discussion with Marley in the church, but one’s family is always worth forgiving—and loving. As aforementioned, Kate is no Mary, but she is Kevin McCallister’s mother, and she realizes her mistake in overlooking him and asks for his pardon. This touching scene with Kate and her son echoes the tenderness found within the image of the Holy Family that we Catholics celebrate during Christmas. Kate fulfills a reunion with her son on Christmas Day.

As Kevin runs into his mother’s arms, another imagery is evoked: the iconic depiction of the prodigal son returning home to his family. While Kevin’s family physically forsakes him, leaving him alone, Kevin spiritually forsook his family because of the bitterness he felt and expressed toward them. Kevin is thus like the Prodigal Son in Jesus’s famous parable. He has lived a life of indulgence, taken his family and their material goods for granted, but he comes to regret his bitter feelings and his selfishness. Once he runs to his mother, the spiritual transformation within Kevin is complete, signified through the stern expression he gives her that gives way to a genuine, tear-filled smile.

In his heart, Kevin has now returned to his family: he has returned home. Luke 15:20 tells of the reunion of the Prodigal Son with his father, echoed in the hallway scene with Kevin and his mother: “And he arose and came to his father. But while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and felt compassion, and ran and embraced him and kissed him.” When I visualize the scene from this parable, as I have many times as a Christian child and adult, I can easily superimpose Kevin’s joyous running toward his mother at the end of the movie to that of the Prodigal Son running toward his father. I invite you to use your imagination in this way now, to see the spiritual where perhaps before, like me, you may have been lost in the material.

After the rest of the McCallister family arrives and provides Kevin with accolades (letting us realize that Kevin’s one-sided picture of them was probably not a wholly accurate one), the movie feels joyous. Yet, significantly, it does not end with this family reunion scene. No, it concludes with Kevin walking by himself in contemplation to a nearby window and gazing outward. The image we see in that window along with Kevin is that of Marley reconciling with his son and hugging his granddaughter, a picture, one might say, of another icon of the Holy Family that ought to be appreciated as they gather together on this Christmas Day. Kevin stares at the tableaux in the window, reflecting on the scene.

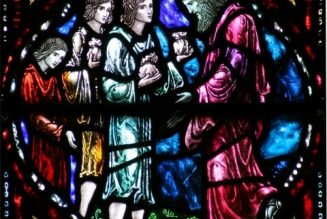

Like Kevin, Marley’s pilgrimage is now concluded, and he is redeemed. Kevin, once boastful and reliant on his own cleverness, has found a shepherd in Marley, a guide who led him through the shadows of danger to the safety of home. It is a metaphorical representation of the divine shepherd leading the lost sheep back to the fold. A sacred picture of forgiveness, it mirrors the timeless stories depicted in the stained-glass windows of cathedrals, where the embrace of divine mercy is told through memorable images like that of the Good Shepherd.

Matthew 18:12–14 resonates here: “What do you think? If a man has a hundred sheep, and one of them has gone astray, does he not leave the ninety-nine on the mountains and go in search of the one that went astray? And if he finds it, truly, I say to you, he rejoices over it more than over the ninety-nine that never went astray.” Marley, in his act of saving Kevin, embodies the shepherd leaving the ninety-nine to rescue the one who went astray. Kevin’s pilgrimage, with Marley as his unexpected guide, becomes a parable of redemption, a journey back to the warmth of family and, symbolically, to the embrace of a higher power.

I considered ending this essay here, but I feel compelled to share one other experience my family had when watching this movie together. Last Christmastide, we watched this movie, and my children began joking about what they would do if criminals ever came to our house. Like Kevin, they planned and plotted. While we slept that night, our family car was stolen out of our driveway, our security cameras picking up only blurry images of those who took it. The irony was not lost on us—the whimsical discussions inspired by Home Alone mirrored in an unforeseen, real-life scenario. This unexpected twist, a concoction of humor and irony, reminded us that life’s script often unfolds in ways we least expect. Such unforeseen plot twists add layers to our personal narratives, emphasizing the importance of embracing the unexpected, trusting in divine providence, and finding redemption amidst life’s unpredictable turns. In the Catholic tradition, challenges are not merely obstacles but opportunities for grace and growth—lessons mirrored in the experiences of Kevin, Marley, and even Kate in the movie.

As we bring this analysis of Home Alone to a close, let us bear in mind that life’s journey is replete with unexpected guides, unforeseen challenges, and, if we remain open to them, moments of profound redemption orchestrated by a higher power. In the broader context of our faith, being with God ensures that we never truly face the risk of being “home alone.” His presence becomes our refuge, transcending the uncertainties of this world and offering a sense of family, belonging, and, dare I say, security to our hearts.

[1] To take the Catholic reading of this film to its full extent, it bears noting that South Bend is the home of the University of Notre Dame, one of the most well-known Catholic universities in the United States and home to this journal. While Marley is not found to be a serial killer, that he hails from the town where Notre Dame is located is never questioned. This fact lends credence to the idea that Marley is a representative of the Catholic faith in the movie. Any astute reader would realize the claim this footnote makes about Marley is in no way a stretch.