The Sanctus, the prayer that begins the Eucharistic prayer or anaphora, echoes the angelic hymn: “Holy, holy, holy!” It is one of the oldest Eucharistic prayers, with parts of it reaching back to the 1st century Didache: “Hosanna to the God (Son) of David! If any one is holy, let him come; if any one is not so, let him repent. Maran atha. Amen.” It is used universally across the most ancient rites of the Church.

The 2010 revised translation of the Roman Missal into English clearly brought many improvements. One thing that bothers me about it, however, is confusion over how to pray the Sanctus. I’ve frequently attended Masses where people hestiate or pray over top of each other, as parishes seem split between two major ways of saying the prayer.

Is it . . .

- “Holy, holy, holy (pause) Lord God of Hosts” or

- “Holy, holy, holy Lord (pause) God of hosts”?

Punctuation doesn’t help either as there isn’t a comma in either location. Taking a look at Scripture, however, can give us some indication, however, for a preferred place for the pause.

First, the title “Lord God of Hosts” occurs dozens of times throughout the Old Testament. Exodus speaks of Israel as the hosts of the Lord, but it’s the First book of Samuel that begins using the title Lord God of Hosts. Although it was first translated in the Sanctus as “God of power and might,” the title can mean Lord of the multiple of people (earthly hosts) or angels (heavenly hosts) or armies. Its use as a standalone title in the Old Testament provides an important indicator when reciting the Sanctus.

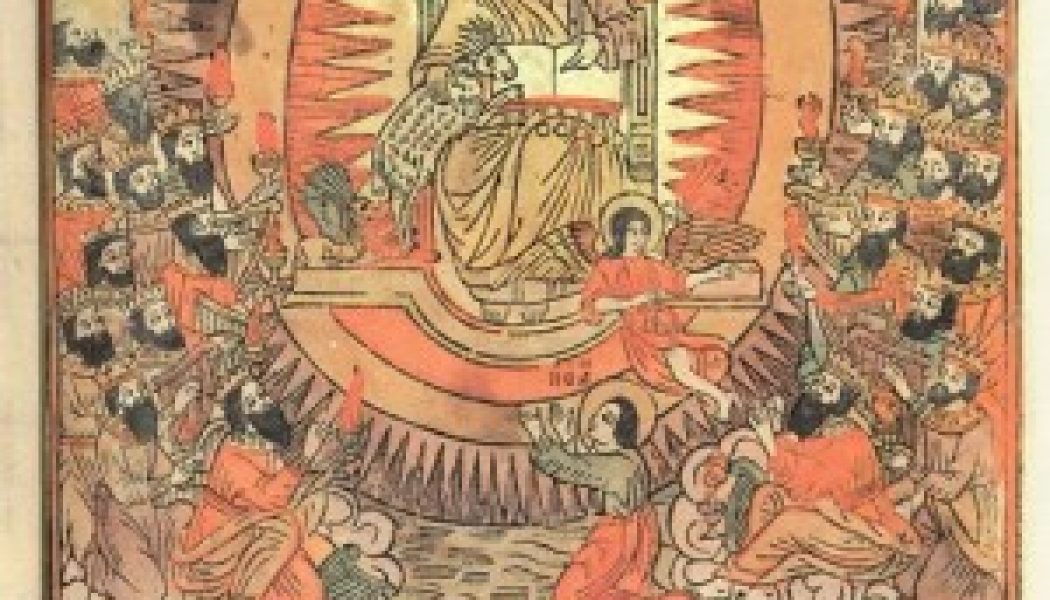

The triple adjective “Holy, holy, holy” in reference to God comes originally from Isaiah 6:3: “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts;

the whole earth is full of his glory.” The triple repetition indicates the superlative in Hebrew, which uses repetition, rather than “more” or “most.” I say adjective but really we could consider this almost as a name for God: He is the most holy one and also the Holy Trinity, a deeper reading that transcends grammatical considerations. Revelation repeats the language of Isaiah in chapter 4 for the prayer of the four creatures surrounded by the twenty-four elders (priests): “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of Hosts.”

In my opinion, it makes sense to pause after the triple invocation, preserving it as coherent superlative in itself and mainting a clear Triniatrian significance, while also perserving the distinct title of “Lord God of Hosts.” When we look at Isaiah and Revelation, both indicate a pulling back of the veil to glimpse God’s throne in Heaven and a joining into the worhsip of the angels and saints.

How to Pray the Sanctus

Not only does the prayer pull back the veil; it also indicates a manifestation. The second half of the Sanctus, echoed by the Didache, points to the coming of the Messiah. Its text derives from Jesus’ entrance into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, linked to his coming at the Mass at this crucial transition into the Eucharistic prayer. The crowds shout: Hosanna! Although the word doesn’t appear in the Old Testament, it was included in the ritual for the Feast of Booths. It is recorded in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and John to describe the crowd’s acclamation of Jesus.

The prayer clearly invokes Jesus as the Messiah, the Son of David, blessing his arrival into the his holy city. Moving from the angels, we join the crowd: “And the crowds that went before him and that followed him shouted, ‘Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord! Hosanna in the highest!’” (Matt 21:9). The word Hosannah is a plea for rescue and salvation. It ties Christ’s coming to his work of salvation, his death on the Cross, that becomes present to us in the consecration.

The Sanctus is an amazing and powerful call to share in the adoration of the Trinity by the angels and also a plea of salvation through the coming of Christ. In a stroke of genuis, the early Church brought these two prayers together, recongizing that the heavenly worship comes down to earth through Jesus’ sacramental presence and sacrifice in the Mass.

In his recent book, Bishop Athanasius Schneider recommends praying it at other times as well:

This prayer was heard by Isaiah from the mouth of the Seraphim. It is the prayer of the angels par excellence. So, oftentimes when I am traveling, in my soul I pray the Sanctus. When I enter a Church, I kneel down and pray first the Sanctus with my guardian angel, and with the angels that surround the Tabernacle; they are there. So, I recommend the use of the Sanctus. . . .

Their [the angels’] beloved prayer is the Sanctus. The essence of every angel says: “God is holy, and God alone is holy, and God is great. We have to magnfiy Him as Our Lady did in her Magnificat.

Christus Vincit (Angelico Press), 292; 295.

Since the Sanctus participates in the song of the angels, I have to end with a musical setting. My favorite Sanctus comes from Gabriel Fauré’s Requiem (1890). It begins with an etheral quality, invoking the lightness of the angels, and transitions to a blast of the Hosannah, like the triumphal entrace of the King: