Pillar subscribers can listen to JD read this Pillar Post here: The Pillar TL;DR

Hey everybody,

Today is the feast of St. Gregory the Great, and you’re reading The Tuesday Pillar Post.

Yesterday was a holiday, of course, and I spent it with my family enjoying the waning summer hours at the local pool. My kids were among the very last to get out of the pool for the summer, and I think that’s exactly how it should be. I hope your Labor Day was equally blessed — and that’s why you’re getting the newsletter a bit after noon, at least if you live on the East Coast.

If you don’t know who he was, Pope St. Gregory the Great was the vicar of Christ from 590 until 604. He was an evangelist, a diplomat, a keen interpreter of Scripture, a beautiful spiritual writer and preacher, and an influential liturgical leader, who standardized liturgical praxis across the Christian West.

He is also the author of a book I think is really important, the Liber Regulae Pastoralis — the “Book of Pastoral Care,” which is a kind of guidebook of hard-won advice for bishops, and by extension, for pastors and others with pastoral responsibility.

The book isn’t sentimental or gauzy, and it doesn’t mince words. This morning, I looked for an excerpt that would capture the text for you, but the problem is this: its general sections, which are exhortations to humility, repentance, and conversion, are less surprisingly interesting than the very specific advice offered to pastors about leading particular kinds of people, with their particular kinds of souls, to Christ.

In other words, the interesting parts of the book just aren’t what make for good excerpts — and if I pull out some lofty-sounding excerpt for you, I think I’ll be doing the actual wisdom of the text an injustice.

So I’m not going to do it. Instead, I’ll say this — if you have a ministry of pastoral care, just read it. Learn from it. Take notes. St. Gregory’s observations in the sixth century are immediately relevant to pastoral ministry today — and that’s pretty cool, when you think of it. And actually, the same is true if you’ve got other leadership roles — including, especially, parenting.

St. Gregory is great (if I may). And I’m not going to do his great work the indignity of a bad excerpt. So just give him a read.

In the meantime, here’s the story of St. Gregory’s legendary Eucharistic miracle — a story which first appeared in the eighth century, and grew with time in the telling.

It seems that the story began with the idea that a woman who baked the bread used for Mass told Gregory once that she found it impossible to believe that the bread she baked, in her very own kitchen, could become the Body and Blood of Christ.

When Greg heard that, the story goes, he dropped to his knees to pray that the woman might have faith — and when he did, a host — which she had baked — changed to the appearance of flesh and blood, restoring her faith, and moving her to weep.

As the story was told, and depicted in art, gradually it became that Christ himself was standing before the congregation after Gregory consecrated the Eucharist — a story meant to convey the profundity of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist.

What part of it is actually true? I don’t know, except for the fact of the real presence itself. But I do think this 1510 painting, from the Dutch master Adriaen Ysenbrandt, captures something cool about what is really happening in the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass:

.

The news

The Pillar broke the news last week that once-popular media personality Fr. Thomas Rosica stands accused in a Canadian lawsuit of sexually assaulting a younger priest in the lead-up to Toronto’s 2002 World Youth Day.

Over the weekend, we broke more news on this story: that Canada’s Bishop Ronald Fabbro, of the Diocese of London, Ontario, is facing a Vatican probe, after a Vos estis lux mundi complaint charged that when the allegedly assaulted priest tried to report Rosica to him in 2015, the bishop was unwilling to hear the complaint, and abruptly ended the conversation.

Fabbro, as it happens, was Rosica’s religious superior in the early 2000s, when the sexual assault is alleged to have taken place.

It is not clear what the Dicastery for Bishops will conclude about the complaint, and — even if they decide it merits a response — past practice indicates that since Fabbro is 14 months from retirement age, the Apostolic See may decide to just wait quietly for his retirement, with perhaps a discrete admonishment to the bishop, rather than make any a public response to the allegation.

But that remains to be seen.

You might not realize that 90% of the East Timorese people are Catholic, and that the explosion of the Catholic faith in the country has happened only over the past 100 years.

But this is a really interesting place, and journalist Filipe D’Avillez has spent the last week talking to a lot of East Timor’s experts and clerics about the country, its culture, and its uniquely Catholic identity.

This is the kind of deep-dive profile on a place — and its people — that I love to read. You’re going to love it too.

Really, give this in-depth report a read. You don’t want to miss it.

—

In February, Germany’s bishops took the rare step of condemning a political party by name.

So has the bishops’ assertive policy against the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party backfired? How much can we read into the election result? And what’s likely to happen next?

Here’s a great analysis, from The Pillar’s Luke Coppen.

—

Many readers of The Pillar know that new norms on seminary formation in the U.S. require something called a propaedeutic year for would-be priests — an initial year of formation focused on learning how to pray, rather than on studies.

As seminaries devise propaedeutic year itineraries, most feature spiritual direction, acclimation to praying the Liturgy of the Hours, short courses on the Catechism or on Christian spirituality, media fasts, and, often, some periods of manual labor — which can be a helpful aid to the spiritual life and to the pursuit of virtue.

The process groups aren’t therapy, and they aren’t some kind of 1980s-style-sharing-circle, either, in which men are obliged to manifest their consciences, or howl like wolves or anything like that.

They seem to me to be more like a guided immersion into genuine brotherhood — fraternal closeness, and even fraternal accountability. For a generation which reports staggering levels of loneliness, that seems to me like a pretty good idea.

Of course, my view of the thing isn’t important. But the men we talked with about this said they found themselves really helped by the groups — which might well become part of propaedeutic formation in other seminaries too.

Michelle La Rosa has some great reporting on the subject, which you can read about here.

In fact, says Chaldean patriarch Cardinal Louis Sako, if the bishops don’t apologize, they could face serious canonical penalties, including the prospect of excommunication. But, according to sources close to the Chaldean Church, the bishops are not likely to meet that deadline — leading to an escalated standoff over leadership decisions in the Chaldean Church.

The background is complicated — and I spent a lot of time on the phone this weekend hearing more perspectives and viewpoints, which I expect will make their way into much more Pillar reporting on the subject in the weeks to come.

Because it’s wrong

This is not a post about politics. Or at least, it’s not a post about who you should vote for in November — your vote is your own.

But I did some reflecting over the weekend on a proposal Donald Trump announced Thursday, which would require either the government or insurance companies — the details are still quite scant — assume the costs of in vitro fertilization treatment for couples.

Like a lot of Catholics — regardless of how they plan to vote — I was taken aback by the idea. Catholics have long fought against the notion of taxpayer funding for abortion, in large part because of their opposition to being made an involuntary cause, however remote, in a chain of events that leads to the unjust destruction of human lives in abortion.

That’s also the reason why so many Catholics groups fought so hard against the HHS contraception mandate — because people like the Little Sisters of the Poor didn’t want to be a link in a chain that would lead to provision of contraception, and thus connected, however remotely, to the moral evil of contracepting the conjugal act.

Mutatis mutandis, the same principle would seem to apply to the idea of an insurance IVF mandate, and I can imagine the same kinds of legal battles being waged if such an idea ever came to pass (for what it’s worth, I think that even if Trump is elected, it’s relatively unlikely this particular plan will actually be implemented).

I posted on twitter.com on Thursday the observation that in vitro fertilization involves the destruction of living embryonic human beings — both those whose genetics make them somewhat more unlikely to survive a pregnancy, and (almost always) those which are “left over” after a married couple has decided they have had enough children, and don’t want to implant their remaining embryos.

That’s true, and it’s not just my opinion, it is the well-documented and consistent practice of the in vitro fertilization industry.

Others, I noticed, posted religious liberty arguments like the ones I made above: That Americans shouldn’t be forced to pay for something they disagree with, and should therefore be given religious liberty protections against a potential IVF mandate.

But while I know my argument was true, and might have even been convincing to some, it also felt somewhat unsatisfying to make — because it’s a secondary argument against taxpayer-funded in vitro fertilization, not the primary one.

Sure, there are plenty of physicians who say the destruction of embryos is inherent to the in vitro fertilization process, and who note that about 60% of patients opt to “screen out” those embryos who “don’t have 46 chromosomes” or who “contain unwanted genes,” according to MedPage. And those same experts estimate that “99% of the time, when people are done with family building and have no need for any remaining embryos, they opt to have them discarded.”

That’s serious stuff, and I expect that, in fact, in vitro fertilization might actually lead to more deaths of more human beings than surgical abortion, and maybe even pharmaceutical abortion — the numbers on in vitro are extremely difficult to come by, which makes it hard to say.

But that’s still a secondary argument. The real reason why Catholics oppose in vitro fertilization is because it’s wrong. It’s wrong to separate the creation of human life from the marital act. That doesn’t make the children conceived by in vitro evil, or unwanted, or unbeloved, but the fact remains that it’s wrong to separate sex and procreation.

Even if no embryos were ever destroyed in the process of in vitro fertilization, it would still be wrong.

Of course, not everything that’s wrong should be illegal. But some wrong things should be illegal, just because they’re wrong. And to date, that’s the conversation I haven’t seen happening. It’s the conversation I myself avoided, when I posted about secondary arguments against in vitro fertilization.

But I found myself wondering all weekend whether we really ought to be making secondary arguments on stuff like this. At the bioethical frontiers of human technology, is it enough to say that we should make sure of religious exemptions, or even that we should limit the harm to avoid direct killing? Isn’t it better for Christians, especially, to say: “This is wrong. Doing wrong things will harm all of us. Technological ability should not be the arbiter of our actions. We should stop.”?

Isn’t it ok for us to lead with morality? Mightn’t leading with morality — being voices for what’s true and good — be a form of evangelization?

Of course, that’s not the same as being politically expedient. The politically expedient arguments are probably the secondary ones. And we often avoid arguing from morality because we’re afraid that doing so makes us seem less reasonable, less realistic, less sophisticated even — and that we, and maybe Christianity itself, will seem weird, if we’re standing on the corner talking about the foreign and ugly concepts of “right” and “wrong.”

But here’s the truth: God has a plan for us that involves both great grace, and real happiness, and often great suffering. Great suffering is unavoidable in this life, and doing/enabling/paying for things that are wrong won’t obviate that suffering. We can’t run from it. We can’t out-invent it. We can only learn to find its meaning in the God of the universe.

That’s why we shouldn’t approve, support, enable, or fund in vitro fertilization. It doesn’t solve the real problems. And it takes us further from our identity as sons and daughters of the Father. It takes us further from who we really are.

That might not be especially convincing. But it has the benefit of being true. And I find myself wondering if telling the truth — whole, unvarnished, and unafraid — isn’t worth more than trying to make ourselves sound less radical.

‘Please remain 8 tablespoons of water’

If you are a regular reader of The Pillar Post, you know that last Friday my partner Ed wrote an especially funny essay about the introduction of canned spaghetti carbonara, about which Ed seemed fairly excited, even while insisting that “no one should eat this. Ever.”

When I read it, I suppose I took Ed’s admonition as something of a personal challenge. And it occurred to me that it wasn’t especially Pillar-like, to be honest. Here at The Pillar, we tend to insist with great pride that we’re not about pronouncing things magisterially — that we prefer to do the reporting, and gather the facts, rather than just issue magisterial declarations about what one ought or ought not conclude, about anything.

So I thought the natural thing to do was to try the canned carbonara Ed had gone on about, to report back faithfully and accurately to you readers, and to let you decide for yourselves. But what Ed didn’t tell you is that Heinz Canned Spaghetti Carbonara is only available in the UK market, where for some reason, Brits refer to it as Spagh Carb, with seemingly no awareness of just how silly it sounds to abbreviate the word spaghetti.

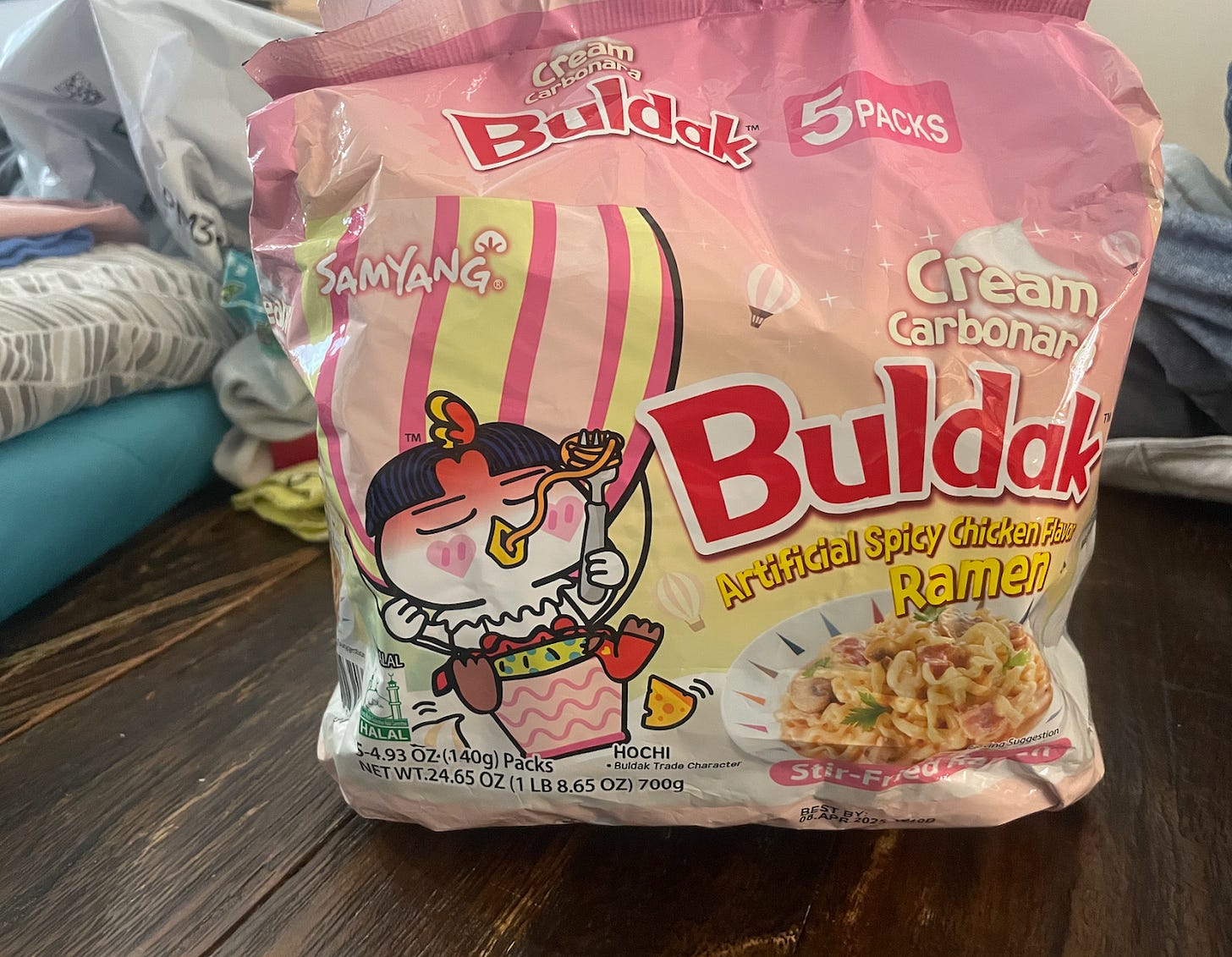

The closest I could come here in the U.S. to canned carbonara was another prepackaged pasta preparation: Samyang’s Buldak Cream Carbonara Spicy Chicken Flavor Ramen, pictured below on my dining room table (alongside some folded laundry).

I ordered the “Artificial Spicy Chicken Flavor Carbonara Ramen” with plans to try it on Monday, and report back to all of you.

But I didn’t know that I had accidentally stumbled into a TikTok trend, and that young zoomers have created a genre of video in which they eat Buldak Creamy Carbonara Ramen for an audience.

Guys, the internet is really weird.

In fact, while I bought a 12-pack for just a few bucks on Amazon, it turns out this carbonara ramen was for a while quite rare, with resellers charging exactly the kinds of markups you’d expect.

But while it was rare and trendy, Buldak Cream Carbonara Spicy Chicken Flavor Ramen was not carbonara. Nor was it delicious.

Still, it was — in the manner of many South Korean products — delightful.

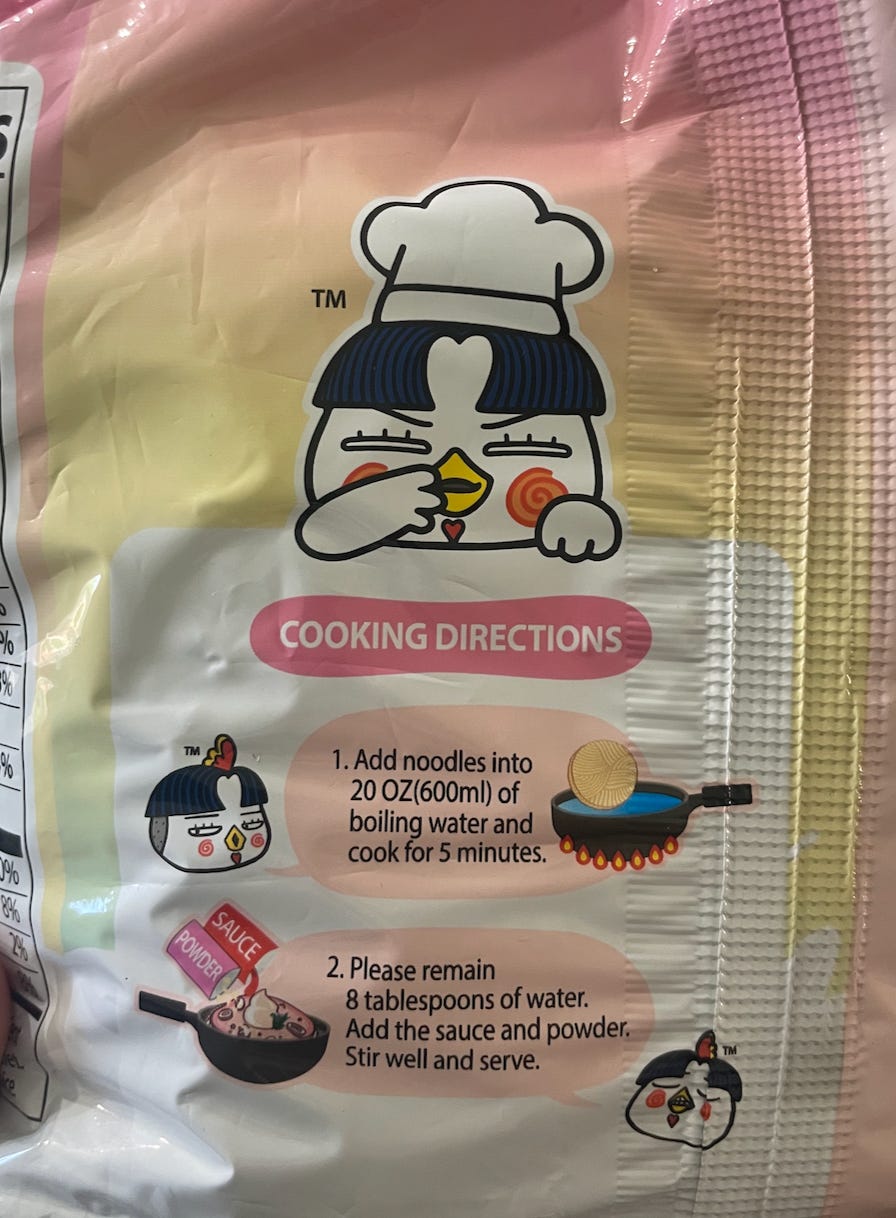

Check out, for example, the cooking directions:

And look at the super-cute “Hochi,” helpfully labeled on the package as the “Buldak trade character,” in case you weren’t sure what she was doing there.

So far as I can tell, Hochi is a young chicken, happily munching on chicken-flavored ramen. This is not cannibalism, because there does not appear to be anything actually close to chicken in the dish.

Nor, for something called carbonara, was there any pancetta, guanciale, or even what I expected — bacon bits.

There was instead a nuclear orange dish of very spicy noodles, with a few green sprigs, apparently intended to evoke a fresh carbonara at a fine Italian trattoria.

Every bite managed to be gummy, heartburn-inducing, and yet somehow laden with enough MSG as to make me want another. And while tiktok helps with the marketing, I am certain the real secret to the success of Buldak Cream Carbonara Spicy Chicken Flavor Ramen is in this mystery envelope of spicy black goo concentrate.

Anyway, after a few bites of the fire ramen, my dining companion Davey tapped out, and went hard to his water bottle:

But I was determined to find the “carbonara” in Buldak Cream Carbonara Spicy Chicken Flavor Ramen.

So the second time, I made it without the spicy black goo, but still using the spice packet labeled “carbonara seasoning.” I mixed in an egg for texture to the hot water, and I undercooked the noodles, hoping for al dente.

But ramen doesn’t do al dente, it turns out, and what I got was a very bland, crunchy — and yes STILL GUMMY — bowl of mild tasting macaroni soup. Covered in parmesan and mixed with some butter, it wasn’t half bad.

I’d rather eat this than eat protein bricks, that’s for sure.

But it wasn’t carbonara. And 20 minutes after I’d eaten about 1,000 calories worth of this stuff, I was hungry again. Next time, I’ll go for the canned Spagh Carb. I bet it sticks to the ribs, if nothing else.

Please be assured of our prayers, and please pray for us. We need it.

Yours in Christ,

JD Flynn

editor-in-chief

The Pillar

Comments 48

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews