It was not until early October that I encountered a full-throated conservative reaction to the Pew finding: the September 29–October 12 issue of the National Catholic Register with its 60-point headline, “Eucharistic Wake-Up Call.”

The issue contained no less than fourteen articles on the Eucharist, including articles on the production of hosts and Eucharistic wine and sidebars on Eucharistic miracles, Eucharistic books and DVDs, and Eucharistic papal encyclicals.

Nowhere did I find any outright blaming of the Second Vatican Council, although there was a lot of familiar grumbling about the post-conciliar “spirit” and lack of catechesis. If many of the articles could have fit into my pre-conciliar childhood, they were less dogmatic and more conscious of contemporary challenges to understanding the sacred. Most of the articles were more positive in proposing remedies than negative in targeting enemies.

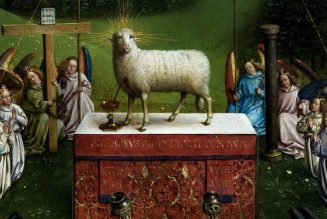

Not that there weren’t grounds for disagreement. The Register articles were full of references to liturgical reverence but not to liturgical participation. There was a lot about the centrality of the tabernacle but not about the mystery of the altar. The transformation of bread and wine often seemed detached from the drama of salvation through death and resurrection, the Mass less a sacrificial meal ritually memorializing Christ’s Passover than a solemn means to “confect” the Blessed Sacrament, enabling worshipers to adore and implore Jesus, whether briefly entombed in their bodies or more lastingly enthroned in the tabernacle.

So liberal Catholics might well be critical of what could be considered a cramped as well as nostalgically pre-conciliar view of the Eucharist. But why were liberal commentators (and not for the first time) so quick out of the blocks with quips about “hair on fire catechetics” and “clerical hand-wringing”? Why did they seem so resistant to any possibility that there has been a serious erosion of Catholic belief in the Real Presence? Why are they not more bothered by findings like Pew’s, or even less drastic than Pew’s?

The puzzle is all the greater because over the years I have participated at countless liturgies of large and small groups of overwhelmingly liberal Catholics, and their belief was palpable, their fervor sufficient to energize St. Peter’s Basilica. So here are my own best answers.

Simple polarization. Let conservatives approve of something and liberals start sniffing for the hidden agenda, probably something to roll back Vatican II. (Conservatives entertain parallel suspicions about anything endorsed by liberals.) To acknowledge that anything at the heart of Catholic belief and practice has eroded since the Council risks handing ammunition to conservative critics. A series of surveys done over many years by William D’Antonio et al. for the National Catholic Reporter always insisted that Catholics were hewing to “core beliefs.” Dissent was limited to questions like contraception, conscience, ordaining women, and so on. An impression of continuity was strengthened by the design of those periodic surveys, which missed the growing number of young people dropping out of the sample in each generation.

Fear of extra-liturgical, para-liturgical, or devotional diversions. The liturgical renewal recentered Catholic spiritual energy on participation in the Mass, after centuries of obstacles to participation had dispersed that energy into devotions, including those surrounding the Blessed Sacrament like Solemn Benediction or Forty-Hours Adoration.

Commitment to social justice and Gospel witness. Do concerns about Catholic belief in the Real Presence reflect an otherworldly, individualistic spirituality of personal salvation? Does so much focus on the sacramental change in the bread and wine eclipse the necessary change in the recipients—and in the world they should be serving?

Naïve or materialist interpretation of Eucharistic change. The history of Christianity has been marked by some strange and distorted understandings of Christ’s presence in the Eucharist. “Barbarian” warriors wanting Jesus to lead them into battle put consecrated bread on their lances. Reports of miraculously bleeding hosts have stirred the imaginations of pious but literal Catholics who envision a tiny Jesus, as physical as on the shores of the Sea of Galilee, crouched within or behind the white veiling of the consecrated bread.

These are all legitimate worries, but they strike me as overwrought. Or, if not overwrought, suggestive of the need for precisely the kind of theological explanation or catechesis that liberal commentators have been swift to spurn.

Reflexive polarization needs no rebuttal. As for devotional and para-liturgical backsliding, a half-century after Vatican II the reformed liturgy is well established. Active participation at Mass is not threatened by every silent prayer of veneration before the Tabernacle or celebration of Solemn Benediction. Investigation might even show that fervent participation is increased. This is not a zero-sum game.

That is also true about belief in the Real Presence and commitment to social justice. The erosion of the former hardly means growth in the latter. At Mass the Lord is present, in distinct ways, in the Word proclaimed, the bread and wine transformed, and the congregation sent forth. There is no reason to assume that playing down one of these transforming modes of presence will strengthen another; no reason to think that the risk of otherworldly individualism—or the commitment to justice and healing—is any less among those choosing a “symbolic” understanding of the Eucharist.

Finally, the constant temptation to concretize a spiritual mystery almost to the point of gross superstition or intimations of cannibalism should warn liberals against dismissing rather than pursuing theological reflection about Real Presence. Such theological reflection, and its corresponding catechesis, must be humble about the inevitable limitations of our language and intellects; but “we haven’t got a clue” is no substitute for rethinking our understanding of transubstantiation. An article by Brett Salkeld in a recent issue of Church Life Journal is an enlightening example of such rethinking and a good advertisement for his ecumenically sensitive new book Transubstantiation: Theology, History, and Christian Unity (Baker Academic).

One ray of common sense in this controversy came from Fr. Raymond J. de Souza in that issue of the National Catholic Register. De Souza contrasted the Pew findings about all self-identified Catholics with much higher levels of belief in the Real Presence found by Pew among weekly Mass-goers. Another poll put the figure among the latter at more than nine out of ten.

So in the end is this all about Mass attendance? I have always believed that many pioneering liturgical reformers were overly confident that the renewed, vernacular liturgy would be its own catechesis; consequently, little was required to instruct people in the pews. But the reformers were surely right about belief in the Real Presence. Again and again throughout the Mass, word and gesture proclaim the Real Presence, even more so, I believe, in the renewed liturgy than in the mumbled Latin ones I knew as an altar server. In this sense, Roberts and Reese are probably correct: most Catholics simply “get it,” without any further need for catechesis or theological explication. If, that is, they are regular Mass attenders. As fewer and fewer are.

Father de Souza has further things to say about secularism and the way “the entire sacramental system has lost its hold.” But he ties this in with the challenge of remedying the massive drop in Catholic Mass attendance, about which he offers more common sense: “Successful programs of parish renewal stress a welcoming community, a sense of belonging to a common mission, good music, and good preaching.”

Much easier to spell out that agenda than accomplish it, for a lot of reasons. Still, I cannot imagine liberal Catholics disagreeing. So why should we view possibly disturbing poll findings about belief in the Real Presence as a dubious distraction? Why not as a compelling call for parish renewal, with all the implied challenges for mission, music, and preaching? Why not as a “wake-up call” for bringing people back to the Eucharist?