By DONAL ANTHONY FOLEY

September is the month traditionally dedicated to Our Lady of Sorrows, and the feast day for this actually falls on September 15, the day after the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross. Clearly, it is very appropriate that these two feasts, representing the sorrows of Christ and our Lady, should be celebrated so close together, given that the Blessed Virgin was the one who stood so steadfastly at the foot of the cross on Calvary during the awful sufferings of her Son.

There are also some other notable Marian feast days in September, including the Feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin on September 8, the Feast of the Holy Name of Mary on September 12, and in England at least, the Feast of Our Lady of Walsingham, also known as Our Lady of Ransom, on September 24.

These feast days are all part of a rich historical tradition. The celebration of the Nativity of Our Lady in the Eastern Church goes back to the seventh century, and it was likewise celebrated during the time of Pope Sergius I (687-701) in Rome, whence it found its way to other European countries. There is no scriptural record of the birth of Mary, but it is mentioned in the apocryphal Protoevangelium of James, which dates from the second century.

The Feast of the Holy Name of Mary expresses the idea that after the name of Jesus, her name represents the highest expression of holiness in the light of her extraordinary sanctity and her role as Mother of God. This feast day was celebrated in Spain originally, but was extended to the whole Church by Pope Innocent XI after the defeat of the Ottoman army at Vienna by the forces of the Polish King Sobieski on September 12, 1683. Sobieski attributed the victory to the intercession of the Blessed Virgin.

The Feast of Our Lady of Walsingham is a commemoration of the shrine at Walsingham in England. Here, in 1061, a wealthy widow, Richeldis de Faverches, after a vision during which the Blessed Virgin took her in spirit to Nazareth to see the scene of the Annunciation, built a replica of the Holy House. This led to the growth of a shrine which became one of the most important in Europe during the Middle Ages — but tragically, it was destroyed in 1538 at the behest of Henry VIII.

The Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows was originally connected with the seven dolors or sorrows of the Blessed Virgin having begun within the Servite Order. In the seventeenth century, the Holy See allowed the Servites to observe this as a feast day, and Pope Pius VII proclaimed it as a universal feast in 1814, the year in which he returned to Rome having been released from imprisonment at the hands of Napoleon.

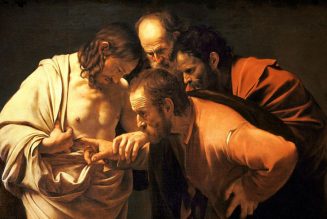

Traditionally, the seven sorrows included the following incidents from the life of our Lady: the prophecy of Simeon that a sword should pierce her soul; the flight into Egypt, when the Holy Family had to escape the wrath of Herod; the loss of the Child Jesus in the Temple of Jerusalem, an incident which was a cause of such anguish to both Mary and Joseph; our Lady meeting Jesus on the way of the cross; the bloody crucifixion of Jesus on Mount Calvary; the piercing of His side by the soldier after His death and the descent of His Body from the cross; and finally, His burial in the tomb of Joseph of Arimathea nearby.

These seven sorrows show how closely linked the lives of Jesus and Mary were, and that she was present at all those crucial moments of pain and distress, and so shared as fully as possible in His sufferings.

And this is relevant to our own time and lives, too, since the theme of suffering is prominent in what our Lady said to the children at Fatima. During the very first apparition, on May 13, 1917, after telling them that they would go to Heaven, she said: “Are you willing to offer yourselves to God and bear all the sufferings He wills to send you, as an act of reparation for the sins by which He is offended, and in supplication for the conversion of sinners?”

Lucia replied, “Yes, we are willing,” to which the response was, “Then you are going to have much to suffer, but the grace of God will be your comfort.”

During the July apparition, she asked them to sacrifice themselves for sinners — which implies suffering — and also showed them the vision of Hell, the first part of the Fatima secret. Hell is a place of unending suffering, but tragically a suffering which has no redemptive value and is a consequence of the rejection God made by those who choose to go there through mortal sin.

After this horrific vision, which only lasted an instant, Sr. Lucia tells us that they looked up at our Lady who spoke to them kindly but with a very sad expression, and then told the second part of the secret, which of itself refers to the wars, persecutions, and martyrdoms which would come if her words were not heeded.

It was during the August apparition, though, that the sadness and suffering of our Lady at the plight of mankind in its opposition to God became most apparent. Sr. Lucia tells us that at the end of this apparition, “looking very sad,” she said, “Pray, pray very much, and make sacrifices for sinners; for many souls go to Hell, because there are none to sacrifice themselves and to pray for them.”

Sr. Lucia also records that this same sadness during the final apparition on October 13, 1917, once again saying that the Blessed Virgin was “looking very sad” as she said, “Do not offend the Lord our God anymore, because He is already so much offended.”

Reparation

This plea, of course, was not particularly directed to the children, but to the world in general, but these instances are thought provoking because we naturally have the idea that now that she is in Heaven, body and soul, our Lady can no longer suffer.

But in some mysterious way, it seems that she does suffer, which on another level is perhaps only to be expected since she is the spiritual mother of all believers — and what mother does not suffer when she sees her children straying from the right path?

Perhaps even more mysterious is the fact that Francisco could speak of the sadness of our Lord. He became aware of this through the light from our Lady’s hands which the seers experienced during the first apparition, and which penetrated their hearts. In this light Francisco could see Christ, and Sr. Lucia records him as saying: “I love God so much! But He is very sad because of so many sins! We must never commit any sins again.”

So during this month dedicated to Our Lady of Sorrows, we can certainly think about the historical sorrows of her life, which came about because she was the Mother of Christ, the Man of Sorrows, but it would also be good to remember her continuing sufferings as the Mother of the Mystical Body of Christ, made up of all generations of believers from Pentecost to the end of the world.

Part of the message of Fatima is that through our prayers and sacrifices, through reparation, we can do something to assuage the ongoing sufferings and sorrows of Christ and His Mother — and also help to bring about peace in the world.

- + + (Donal Anthony Foley is the author of a number of books on Marian Apparitions, and maintains a related website at www.theotokos.org.uk. He has also written two time-travel/adventure books for young people, and the third in the series is due to be published next year — details can be seen at: http://glaston-chronicles.co.uk.)