Happy Friday friends,

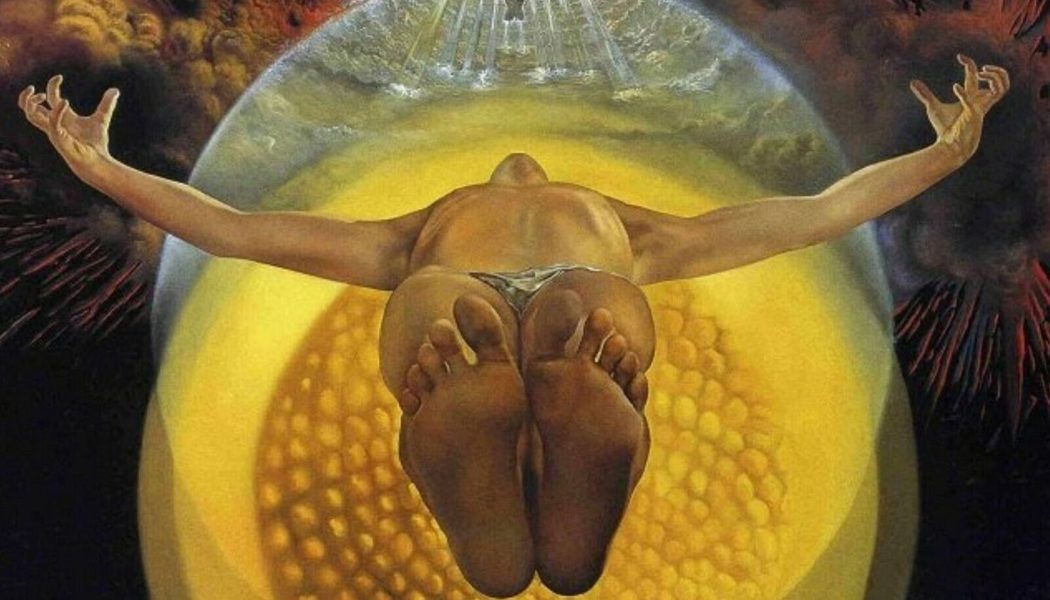

And a Happy Feast of the Ascension to those of you who have already celebrated it.

The Feast of the Ascension of the Lord, of course, properly falls on a Thursday every year, taking place 40 days after Easter, when Christ departed into heaven in view of his disciples.

But since the mid-1990s, observance of the feast has been transferred to the following Sunday in many places, including throughout much of the United States, though of course, not everywhere.

Of course, Ascension Thursday, or Sunday, is also the time of year when the Church’s pub bores come out to lecture the world at large on the invidiousness of transferring feasts in general, and this feast in particular, and how it all shows that the practice of the faith is going to hell in a handcart and being dumbed down along the way.

And, well, sorry, but I’m one of them.

I’m aware of the general theory that moving the feast to a Sunday is meant to “encourage” more Catholics to celebrate it.

OK fine, I guess.

But while I am familiar with the underlying assumption that otherwise Mass-going Catholics will simply ignore the feast unless it’s moved, I’ve yet to see any especially credible data to support it. And even if the data is out there, I’m not sure moving the feast to Sunday to accommodate that behavior is the best way to stress the feast’s central importance to the Easter season.

That same assumption would also seem to fly in the face of the experience of other places, like England and Wales, where the Thursday observation has been restored without the world ending, the people of God revolting, or popular piety collapsing.

For sure, it requires some flexible pastoral provision to accommodate people in the middle of the working week, but the necessity of making an extra effort to mark the day cuts both ways — institutionally and individually — it seems to me.

But all of this is secondary, to my mind. Moving the feast is just plain ugly.

We mark times and seasons in the Church because they are instructive for our rhythm of life. Periods of fasting and feasting, anticipation and celebration, have a catechetical value and habituate us to a pattern of living throughout our lives.

Days and times ground us in history, too; taking particular moments in the present and past and linking the two.

The date of Easter is fixed according to the lunar calendar, it’s linked to the Jewish celebration of Passover to which the triduum of Christ’s passion and resurrection is inextricably joined in time and salvific history. His ascension into heaven 40 days later is not an arbitrary period of time, it is pregnant with meaning, recalling the 40 years in the desert, and bookending the 40 days he spent in solitude before his public ministry with an equal number spent in the company of his disciples after his work was accomplished.

We discard all this, and its significance, at our peril and to our own detriment. At least I think so.

More practically, as we consider how best to “encourage” ourselves as the people of God to celebrate better this season and this feast, it’s just bloody hard to pray a novena between Ascension and Pentecost if you only have seven days to do it.

Beauty, time, rhythm, order, these are all connected, and can serve to connect us to God. The alternative is what, arbitrary convenience? It’s giving up a birthright for a bowl of lentils.

The News

Seemingly coordinated attacks began late Monday night on nine northern Nigerian communities. So far, at least 100 people have been killed, and the violence is ongoing.

The killings come amid years of violence in northern and central Nigeria, perpetrated by Muslim Fulani herding communities and Islamist terrorist groups, and the victims are mostly Christian farming villages.

Most of those who died in the violence this week were women and children. You can read our report on the violence and the government’s response (such as it is) here, and I would urge you to do so, but it is not an easy read.

I have no immediate answers for what any of us can do to help the desperate and ravaged people — our brothers and sisters — but I am sure that for us to look away from this slaughter is somewhere on the spectrum of helping it continue.

One thing I know for sure we can do is pray. Pray for Nigeria.

Pray for peace.

—

Caritas International, the Vatican’s umbrella group for Catholic aid agencies worldwide, got a new leader this week, an Englishman named Alisdair Dutton. He has quite a task ahead of him. Caritas is coming out of a wholesale change of leadership after the pope sacked its top team in November last year.

He’s also something of an interesting character. A former Jesuit novice who led the Scottish Catholic International Aid Fund prior to his election as Caritas secretary-general, he is referred to as a parishioner on the website of the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin in Oxford, “a vibrant, welcoming, and inclusive church” within the Anglican Church of England.

Dutton also spent time as an advisor to David Cameron, the former British prime minister, and is credited in large part with writing the Cameron government’s foreign aid policy.

He’s also been described as something of a “David Brent character” (that means Michael Scott, for American readers), prone to blasting techno remixes of Greta Thunberg speeches from his iPhone during meetings.

You can read all about Dutton, and the state of play at Caritas, right here.

—

By this point in any papacy, with the Holy Father north of 85 and the veteran of an urgent hospital stay, a certain amount of conclave forecasting is inevitable.

There’s a shortage of obvious candidates. And if any one name does start to get a little traction as a possible papabile, it seems like it’s only ever a matter of time before they come under fire in the press. Left, right, or center, a cardinal that flies too high these days is likely to get shot at.

—

The state government in New South Wales, Australia, is dropping a plan to forcibly absorb the Catholic trust which funds and cares for local Catholic cemeteries.

There is, to be clear, something of a shortage of land and funding for cemeteries in the region. It just so happens that Sydney’s Catholic Metropolitan Cemeteries Trust (CMCT) isn’t short of either. But that didn’t stop government ministers trying for what Archbishop Anthony Fisher called an act of “brazen disregard for people of faith.”

Now the Labour government has junked the plan and instead opted to combine four of the region’s five cemetery operators into a single government body, and leave CMCT alone.

It’s a win for the CMCT, and for the Archdiocese of Sydney. And it’s an important win for Catholic institutions in Australia right now. Last we reported on how the government of the Australian Capital Territory is planning to seize an entire Catholic hospital and nationalize its assets and staff — all without consultation of any kind.

Stay up to date with the whole situation here.

—

European ambassadors to Iraq have expressed their solidarity with Cardinal Louis Raphaël Sako after what they called “recent public attacks against his person.”

In a May 8 interview, Sako criticized Rayan al-Kildani, the leader of the Babylon Movement, a party holding four of the five seats reserved for Christians in Iraq’s parliament. Al-Kildani, a Chaldean Christian, is subject to U.S. Treasury sanctions related to his role as head of the 50th Brigade of the Popular Mobilization Forces in Iraq’s Nineveh Plains region.

In response to the criticism Sako has since faced, representatives from 11 European countries wrote to praise the cardinal’s record of working “to protect the rights of Christians on the soil that they inhabit for two millennia.”

Read all about what is going on here.

Out of sight

As we were getting ready to publish our most recent dispatch from Nigeria, we had to have a conversation in the newsroom. As those of you who have read the story know already, it includes some deeply upsetting images.

Pictures of women and children dead, in the street, in mass graves, on the flatbeds of pickup trucks.

We had to discuss not just which of the images we should include, but what kind of warning, if any, we should put at the top of the report.

As you can see, we did post a cautionary note about what readers would see. But part of me didn’t want to. After all, what else should we expect when reading a report about the killing of a hundred innocent people but to be disturbed?

We had to judge, too, when the pictures were needed to drive home the heartbreaking reality of what is going on in Nigeria. That included weighing what would be gratuitous versus the relative absence of any similar coverage of what’s happening in other Western media.

There is a line, somewhere, between telling a story in full and showing more than that requires just because it could be shown. And it’s a line we need to keep behind, as best we can.

But as for the risk of shocking and upsetting our readers, well, I want you to be upset and shocked. I am shocked and upset by what we are reporting. There is simply no way of telling this story, or understanding it, or of doing justice to the people we are reporting on that doesn’t require us to be shocked and upset by what has happened to them.

I heard before, in response to similar images in our past reports from Ukraine, that some readers find the pictures too upsetting. I recall one writing to tell me that they had made her feel “triggered” and unable to sleep. I take her point — it’s why we have the cautionary note.

But at the same time, what right have any of us to a version of these people’s suffering that doesn’t keep us up at night?

Isn’t the fact that few, if any of us, are losing sleep over their lives the reason the people in these Nigerian villages hold no real hope for help arriving?

Again, I have no practical roadmap for changing the reality on the ground in Nigeria. And I don’t know how to save a single life in a single village. But I am disturbed enough by what is happening to help make sure their story is told. And maybe if enough of us tell that story, and enough of us are disturbed by it, we can come closer to some kind of answer. At least I pray we can.

As I said, for myself, I don’t know what I can do to help stop the violence in Nigeria. But we want to make sure we are doing everything we possibly can for the people there. So from now until July 1, we’ll be sending the first $10 of every new subscription to help Christians in Nigeria.

We’ve decided to talk with Nigerian Church leaders on the ground about what local charity, run by Nigerians themselves, we can best support. We’ll keep you posted. In the meantime, if you want to join us in supporting Nigeria’s Christians, one way you can do that is to subscribe, or give a gift subscription.

Out of time

As most of you who have been reading this newsletter for a while know, I have strong opinions about baseball and the glut of rule changes brought in across the major leagues.

From automatic runners on second in extra innings, to the universal designated hitter rule, to bigger bases, I’m against it all. The whole stupid made-for-TV-and-in-app-gambling circus. And I am absolutely against the pitch clock, which started its infernal ticking this year.

For those of you unaware of the new rule, there is now a running countdown of 30, 20, and 15-second intervals between when pitches must be delivered to the batter, depending on the situation — new batter up, bases with runners on, or bases empty. If a pitcher misses the clock, it’s a ball; if the batter isn’t in the box ready to swing, it’s a strike.

I’ve resisted weighing in on the innovation for a couple of reasons, but mostly because others have made better versions of some of the same arguments I would, so it hardly seemed necessary to chime in. But people keep asking me what I think, and others, whose opinions on these things I used to trust implicitly, have now lost their way, so here I go.

Let’s start by conceding some basic facts: the league brought in the pitch clock because a lot of people said it’s what they wanted, and, in general, most people seem to like it now that they have it, because they all agree that the games had become “too long.”

Now, “too long” is a relative assessment, and given my adherence to the philosopher Alva Noë’s conception of the beauty of infinite baseball, I’d argue that it’s also nonsensical. The character of the game is defined by its relation to time. The pace of play is something that is contested between the teams, between pitchers and batters, just like the score, because if you can control the flow of an inning by disrupting your opponents’ rhythm or getting into your own, you can (to a degree) impact your own performance and that of the opposition.

To speak of a game, or games, as “too long” is a kind of category error, it would be better to say the game has become “too much.” The game, and individual games, take as long as they take, because how long they take is a function of how the contest is played out.

But it is true and fair to say games have become longer than they used to be — more than half an hour longer than they were in the 1970s and 80s.

It is also true and fair to say that much of the extra game time has come, not from tense high strategy battles of will, but from pitchers scratching around the mound between throws like demented hens, and batters stepping out between pitches to tighten and retighten the velcro on their gloves as if they all share a common nervous disorder.

And it is absolutely true that the clock, so far, has clawed back an average of 20 minutes of game time from these kinds of compulsive theatrics — and people by and large seem very happy about that, even early pitch clock skeptics.

But, all of that said, I still think it is malum in se, and a corrosive poison to the game.

I have three principal objections to the pitch clock, and for the sake of calling them something, let’s call them the philosophical, the social, and the practical.

—

The philosophical problem with the pitch clock is that, just like all the other recent rule changes, it injects something external and arbitrary into the game.

As a general rule (and again I’m not the first person to make this point) the more rules you make for a game, the less organic and natural it becomes, and the further you remove it from a true sporting contest. Instead, the game becomes ever more influenced by arbitrary factors which have nothing to do with the players’ relative prowess.

Whether a pitcher takes 16 or 14 seconds to decide what pitch to throw can now matter more than what he throws and how well he throws it. That’s just bad for baseball. From where I sit, you’re either pro-tinkering, changing the very fabric of the game by adding arbitrary rules, or you’re agin’ it.

As a matter of philosophical coherence, you cannot pick and choose which you like and would allow depending on your preferences as a spectator.

To argue, as one friend has, that “the extra-innings zombie runner is an abomination,” and to “regret the universalization of the designated hitter” because it stamps out differences between the leagues, but to welcome the pitch clock because you like its effects is, I would submit, to say you’re open to living with an evil for the good it achieves.

Perhaps you think that counting down from 30 is a morally neutral act? It is not.

—

The social problem with the pitch clock is that it proposes a technocratic solution to a cultural problem.

It wasn’t a rule change between 1980 and 2022 that made games nearly 40 minutes longer, it was a drift in the style and rhythm of play which, I freely concede, stems from a culture of bad habits. But to try to correct a general cultural trend with the blunt instrument of new law and technology is, I believe, almost always a mistake and rarely achieves its end without collateral damage.

The freedom of the game to unfold as it will shouldn’t be interfered with unless it is essential — and even then in as minimal and targeted a way as you can, otherwise you simply introduce new forces and factors which can have an unknowable butterfly effect.

If batters are eating up 15 minutes a game playing with their gloves, I can see a fine case for banning them. Ted Williams and Hank Aaron didn’t need gloves, after all, and if an innovation is the problem, roll back that innovation, don’t introduce another one.

An even softer corrective would have been to give umpires the power to call a delay of game strike or ball after warning a batter or pitcher to quit fussing around between throws.

Sure, this would have led to the occasional insane miscall by an umpire, but you can argue an ump, you can shout him down, you could even limit the potential effects by saying delay of game calls can’t make a third strike for an out or a fourth ball for a walk. And all of it could find its place within the game’s existing customs and rhythms.

A pitch clock, like a robot ump, doesn’t get it right every time, nor does it make everyone happy, it just strips nature and humanity out of one more part of the game.

On top of that, we are now likely to see a whole new culture of gamesmanship grow up around playing chicken with the pitch clock, with batters stepping out and back into the box in a way most calculated to distract the pitcher, who now has to have one eye on the countdown while trying to judge his man, check his bases, and read his signs.

—

The practical issue with the pitch clock is simple enough — this is going to swing the results of games. Outs, wins, losses, divisions, and pennants will all be determined by the clock. Not every game, and not even every season, but it will happen.

Maybe fans like getting out of the ballpark 20 minutes earlier, but I suspect they will like it a whole lot less when it involves their team drawing a third out for a clock violation in the bottom of the ninth with bases loaded.

And when it swings a crucial inning in a playoff series or, heaven forfend — but it’s going to happen one day — a championship?

Well, I hope those 20 minutes were worth it.

I haven’t even mentioned how creating a virtually undetectable way for players to draw intentional strikes or balls against themselves is a huge invitation to corruption and spot-fixing from the seedier elements around the sports betting industry, which the league has been courting so furiously for years now.

I could go on and on. But I won’t. Because even if there’s more to say, it seems most people are more interested in getting things wrapped up in a hurry than letting them come to a natural end.

It’s their loss, sure, but it costs us all.

See you next week.

Ed. Condon

Editor

The Pillar

Comments 28

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews