ASSISI, Italy – Though no one’s done the math, it’s possible the central Italian region of Umbria has produced more Catholic saints per capita than anywhere else. Something about the rolling hills, mountains and streams here seems to inspire mystics and seekers; as Italian poet Vittorino Andreoli put it, in Umbria, “Places are built to be part of a city of heaven, not an angle of the earth.”

From St. Francis and St. Clare of Assisi to St. Benedict of Norcia, the roll call of Umbrian halos is legend. Saintliness even seems to run in the family – St. Cesidius, a third century martyr along with his companions Placidus and Eutichius, was also the son of St. Rufinus, the first bishop of Assisi and the city’s original patron saint.

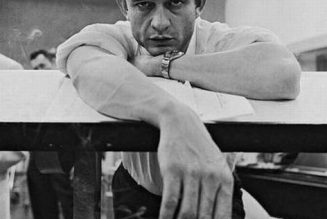

The latest entry into this fellowship of faith is Carlo Acutis, set to be beatified in Assisi on Oct. 10, after Pope Francis in February approved a report of a 2013 miracle attributed to Acutis involving healing a young boy in Brazil from a rare form of pancreatic cancer. Acutis died from an aggressive form of leukemia in 2006, and his beatification process began in 2013.

Though Acutis isn’t actually from Umbria – he was born to Italian parents in London in 1991, and spent most of his life in Milan – his family visited Assisi for a stretch each year around Easter, it was Carlo’s favorite place, and where it’s where he asked to be buried.

Acutis is known for his mastery of computer technology, spending his spare time designing an online exhibition about Eucharistic miracles around the world that’s still making the rounds. He’s being presented as a role model for youth, a “saint of the ordinary,” and also a possible patron saint for IT workers.

His remains are preserved in Assisi’s Santuario della Spogliazione, literally the “sanctuary of taking off clothes,” marking the spot where St. Francis in the early 13th century stripped naked to renounce his worldly heritage and begin anew. In advance of the beatification, Acutis’s body has been brought up from the crypt and is currently on display in a glass case in a side chapel.

Archbishop Domenico Sorrentino of Assisi – also a transplant to Umbria, as Sorrentino originally hails from Naples – is happy to claim Acutis as one of their own.

“Many people here remember him,” Sorrentino told Crux Oct. 5. “They tell me, ‘Ah, I remember Carlo when he came in my shop,’ or ‘I remember Carlo when he used to walk this way with his dogs.’”

“I think it’s a special grace for this city,” he said, speaking from the archbishop’s residence next to the sanctuary.

Sorrentino has been in Assisi for 15 years now, meaning he’s seen countless pilgrims drawn by the great saints come and go. He said he’s noticed something striking: They’re all inspired by those figures, but they rarely imitate them.

“Many people come for St. Francis and St. Clare, saints of eight centuries ago. Many people admire them, and many things are done in the names of both,” he said. “But sometimes they come here and only admire them.”

“Now we can give them someone close to our time and say, ‘You can go this way,’” Sorrentino said. “I hope this will be a great message for everybody, not just young people but especially young people.”

Sorrentino has written a short book about the points of contact between St. Francis of Assisi and Acutis titled Originals, Not Photocopies, a reference to one of Acutis’s favorite sayings: “Everyone is born original, but too many die as photocopies.”

(Befitting a saint of the digital age, Acutis had a flair for memorable phrases of less than 280 characters: The Eucharist as a “highway to heaven,” for example, and “not me but God,” which is a rhyme in Italian: Non io, ma Dio.)

Among other things, Sorrentino stresses that while Acutis strove for holiness, he was hardly perfect. He records some of the disciplinary notes in the future saint’s middle school record: “Acutis disturbs the class and doesn’t have his homework” … “Acutis clowns around.” All that places the new blessed squarely within everybody’s frame of reference, Sorrentino said.

“People come here to try to imitate Francis, but if you can’t, at least try to imitate Carlo,” he said.

Looking at the remains of Acutis today, it’s easy to see why such a figure seems more within reach. He lies in response not wearing ornate clerical vestments or a religious habit, but rather Nike sneakers, blue jeans and a blue soccer jacket. Except for the rosary in his folded hands, he still looks like the typical Italian teen you’d see on any street corner, mall or playing field in the country.

“If you go around St. Peter’s, most saints don’t look like that. He’s very much on our level,” said Monsignor Anthony Figueiredo, an American priest and longtime figure on the Rome scene now on assignment to Sorrentino in Assisi to assist with international pilgrims.

A former secretary to disgraced ex-cardinal and ex-priest Theodore McCarrick, Figueiredo last year released private correspondence about McCarrick’s dealings in Rome that was published by Crux and CBS News.

“Many young people think saints are on altars, they’re unreachable and unattainable, so they think ‘I can never be a saint’,” Figueiredo said. “You look at Carlo Acutis, who was very normal in many ways, but who put Jesus at the center of his life, I really believe he has a winning ticket.”

Acutis’s keen Eucharistic faith has obvious relevance at a time when polls suggest declining faith in the real presence among the Catholic rank and file; a Pew Research Center study last year, for example, found that only 31 percent of US Catholics believe that “during Mass, the bread and wine actually become the body and blood of Jesus.”

“The faith of Carlo is really Catholic, in the deepest sense of the word,” Sorrentino said. “He used to experience how Jesus is really there when we take this piece of bread and eat, and when we adore him … Carlo had this experience at the heart of his spirituality.”

Yet Sorrentino stressed that Acutis also linked his Eucharistic faith to social concern.

“What’s important is that Carlo looked at the Eucharist in the whole sense of this mystery,” he said. “This is not only our unity with the person of Jesus, but also our unity as the body of Christ, the church, and also looking at the world and all humanity. That’s especially so when we find humanity that suffers, the poor.”

In Acutis’s honor, Sorrentino said he plans to announce an annual prize to support development projects in impoverished nations, to be called the “St. Francis and Blessed Carlo Acutis Prize for an Economy of Fraternity.”

There’s a certain irony in styling Acutis as a beacon for the young, since, reading his life, one wonders at times how he actually came off to his peers. You almost get the sense he would have been that nerdy, slightly fussy kid in junior high more popular with adults than kids, and who drew snickers behind his back at recess. The story is told, for instance, that he once saw a couple making out in the Assisi swimming pool and, because there were little kids present, he complained to the lifeguard – sound morality, perhaps, but hardly the kind of thing likely to elicit high-fives and Instagram likes from a gaggle of pre-teens.

Yet even in that sense, Acutis is very much a figure of our time, someone who exemplifies a thirst for God despite his quirks.

“Sometimes when we think of a saint, it’s because he’s done something extraordinary. We have the idea that they’re very far away from us. But being a saint is our normal vocation as Christians, it’s not something extraordinary,” Sorrentino said.

“A saint is not about charisms or miracles or something special. Being a saint means being united to Jesus, and to live according to the values of Jesus,” he said.

“This was the point of the life of this young man,” Sorrentino said.

Naturally, such lives can sprout up anywhere. But somehow it seems only fitting that this “everyman” youth, now a role model for a borderless virtual age, nonetheless is so firmly rooted in the physical space of Umbria, where the soil seems to cultivate exceptional wine and exceptional virtue in almost equal measure.

Follow John Allen on Twitter at @JohnLAllenJr.