Raked by frothing waves and howling wind, the galleon San Felipe rode the merciless Pacific bereft of mainmast and rudder, her battered old hull the merest plaything of the tempest. Aboard her were a litany of friars — Franciscan, Dominican and Augustinian — clinging for their lives to whatever handholds the creaking old behemoth could provide and praying for deliverance, if not for themselves, then at least for her proud Spanish captain and his crew. All had been alarmed by signs in the heavens — first, a blazing comet, then crosses burning in the clouds, seemingly pointing toward Japan.

The San Felipe had been bound for Acapulco in New Spain. An old workhorse heavy-laden with fine Chinese silks and other riches, she was grossly overloaded, well beyond the limit for safe sailing. She had left Manila on 12 July 1596, and well into her journey she was hit head-on by the last typhoon of the season. Not only did that raging tempest rip away her mainmast and her rudder; it carried her along on its rampage to Japan, dumping her at last off the west coast of Shikoku, near the port of Urado, on Oct. 19.

San Felipe’s pilot, Francisco de Olandia, wanted to limp his vessel down the coast to Kyushu and on up to Nagasaki, Christian haven, with a makeshift rudder. The exhausted passengers, however, insisted on putting in to port at once, and their demands won the Captain, Matías de Landecho, over to their side.

The pilot duly sounded the harbor at Urado and came back with bad news: a sand bar lurked underwater; the overloaded galleon would scrape bottom; some cargo must be offloaded first to lighten the ship.

The local ruler, Chōsokabe Motochika, forbade that necessary move. He offered, though, to tow the ship in and dredge a passage if needed. He at once enforced his “offer,” sending 200 armed boats out to tow the galleon straight onto that sand bar, breaking San Felipe’s back. Now she was a shipwreck, and now, by Japanese law, her rich cargo was forfeit.

Motochika sent a dispatch to the warlord-ruler of Japan, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, with an inventory of the treasure-trove he had just purloined, expecting a rich reward.

Hideyoshi was elated. He sent a man down at once to confiscate the cargo — who “even seized the gold that the shipwrecked Spaniards carried in their pockets.”

Historians have noted that Hideyoshi’s vengeful war in Korea, in addition to rebuilding in the wake of recent earthquakes, was draining his coffers. His driving force, though, is best explained in the words of Fray Pedro Bautista, Franciscan: “His greed devoured and engulfed everything.”

Captain Landecho sent his pilot, along with a friar-interpreter, on an embassy of protest to Hideyoshi, who had previously guaranteed security for Spanish shipping. This embassy was waylaid by Hideyoshi’s own confiscator, Masuda Emon, who asked the pilot to explain how the King of Spain had conquered his vast empire spanning the globe. Francisco de Olandia purportedly told him that first they sent in friars to suborn the locals, who then joined ranks with invading Spanish troops to take over the country. One Jesuit historian wrote that the wound this rash answer inflicted was still gushing blood 120 years later.

At any rate, it served as a pretext for Hideyoshi to explode into a rage and demand the execution of all Catholic priests in Japan. He soon realized, though, that without the intermediation of the Jesuits, he would be hard put to strike profitable deals with the Portuguese merchants bringing Chinese silks and gold from Macao. Thus, he moderated his orders: his men were to round up all religious in his capital of Osaka and the nearby imperial city of Kyoto. They would then cut off their ears and noses, parade them in oxcarts through Kyoto, Osaka, and nearby Sakai, and march them southwest to Nagasaki, where they would be crucified.

Ishida Mitsunari, Governor of Lower Kyoto, mercifully intervened. At Captain Landecho’s request, he ordered his men to clip only the left earlobes of the prisoners, who numbered 24. The blood-letting began on Friday, Jan. 3, 1597, at a crossroads in Upper Kyoto. The youngest prisoner, 12-year-old Luis Ibaraki, laughed when they cut his ear, and Thomas Kozaki, 14, dared them to cut his, saying, “Come on, cut me and shed the blood of Christians!”

After this mutilation, all 24 were loaded onto oxcarts, three martyrs in each, and paraded around Kyoto, the imperial capital. All were Franciscans but the three in the last cart, Jesuit Brother Paul Miki and his two lay catechist companions. Many called Paul Miki the best preacher in Japan; he preached ceaselessly along his via crucis. The two catechists, John Goto and James Kisai, would become Jesuits before they mounted their crosses.

With their ears dripping blood, the three youngest — Luis, 12, Anthony, 13, and Thomas, 14 — sang the Our Father and the Hail Mary from their oxcart while others preached to the crowd, a spectacle that must have dazzled even the hardest of heart.

This parade was repeated in Osaka and Sakai. Then, on Jan. 9, the martyrs began their brutal winter’s trek to Nagasaki, a journey of 27 days. They traveled daily from dawn to sunset in single file, sometimes on foot, sometimes on horseback, until they reached their lockup for the night. Brother Miki used every opportunity to preach, and many wrote letters that have been handed down to us.

“You should not worry about me and my father, Michael,” Thomas Kozaki, 14, wrote to his mother. “I hope to see you both very soon there in Paradise.” His father was with him on that via crucis; the bloodstained letter would be found on his crucified body.

To the Jesuit Provincial, Brother Miki wrote, “Please don’t worry about us three and our preparations for death, because by divine goodness we go there with joy and happiness.”

Perhaps the most bitter leg of their journey was their last night on earth, spent huddled, freezing, in three boats moored in Omura Bay offshore of Togitsu, a fishing village. The men in charge feared a Christian uprising if these bloodied religious were to be lodged ashore, for Togitsu was just north of Nagasaki, the Rome of Catholic Japan.

Come morning, the road to Nagasaki was indeed lined with Christians, but there was not a hint of danger. Rather, the air was electric with a holy silence, all Nagasaki dumb with grief, as the parade of martyrs marched past toward Nishi-zaka, the hilltop where their crosses waited. The martyrs’ number was now 26, two laymen having been robbed and thrown in with them enroute by greedy guards. Neither protested, but accepted martyrdom as a blessing.

Atop Nishi-zaka lay the crosses. Although the climb was steep, young Luis was full of energy and asked, “Which cross is mine?” Then he ran to the one pointed out, lay down and hugged it: this vessel would take him home.

Unique among the Twenty-Six, Luis had been offered a chance to save his life. The sheriff in charge of this execution had orders to crucify only 24; he wanted to save this innocent boy and offered him the chance to be his page — on condition that he stop being a Christian. “I do not want to live on that condition,” the brave boy replied, “for it is not reasonable to exchange a life that has no end for one that soon finishes.”

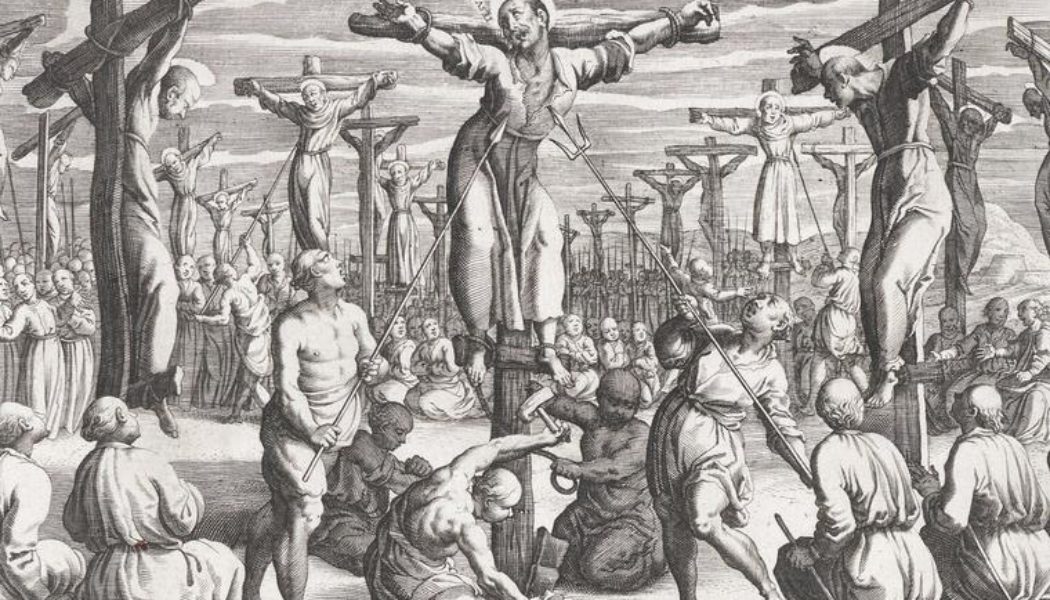

The crosses rose; Paul Miki began his last sermon, preaching that the only way to salvation was through Christ; the three youngest boys sang a Psalm, “Praise the Lord, ye children”; some sang the Te Deum and the Sanctus; and then the coup de grâce.

Japanese crucifixions ended with paired spearmen driving their spearheads up into the flanks of each victim, through the heart and out the shoulders. On Nishi-zaka two pairs began their work, starting at opposite ends of the row of crosses and working toward the center. All, both the martyrs and the crowd, started chanting Jesus! Mary! as the martyrs’ hearts were pierced one by one.

Before the spearmen reached young Luis Ibaraki, he was struggling to climb toward Heaven, and these words of hope burst from his lips: “Paradise, Paradise!” he shouted, his 12-year-old heart still beating. “Jesus! Mary!”

Words that no raging tyrant can ever hope to still.

Luke O’Hara became a Catholic in Japan. His articles and books about Japan’s martyrs can be found at his website, kirishtan.com.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity