My grandmother told me I would hate Greece. “It’s an ugly country,” she said. Her father came from Greece in his childhood, and she had been there a few times, but only during difficult times with her family, which I think soured the experience for her. What I would find awe-inspiring about the country, she said, was the sky. “There’s no other blue like it in the world,” she told me.

When I went to Greece, as a Catholic philosopher attending an Orthodox theology conference, I didn’t find the country ugly at all. On the contrary, I found it spectacular. As I drove from Athens through the pass of Thermopylae (the same pass where the Spartan Leonidas held off the Persian invasion of Greece), the mountains and rocks reminded me of one of my favorite places in the world, the sacred landscape of Pahá Sápa, the Black Hills of South Dakota, which also have their own unique sky. Greece, I found, was a place of rough beauty, rendered even more beautiful by centuries of associations. Even the signs at the highway exit signs evoked a strong aesthetic sense: Thebes (founded by Cadmus, against whose gates the seven fought), Mt. Parnassus (home of the Muses), Tanagra (where Darmok met Jalad).

Looking out from my hotel room in Volos, on the Pagasetic Gulf, I could well believe that the nymph Thetis had once dwelt there, that Jason put forth from those shores in his quest for the golden fleece. When a friend took me to an old stone restaurant high on the slopes of Mount Pelion, with a fire crackling on the hearth and the dense woods around us, it would have seemed utterly natural to glimpse a centaur there in his natural habitat. Looking down upon those long, olive-covered ridges and out to the islands, I felt the thrill of dining in the place where Eris had thrown the golden apple, when the gods still dined upon earth.

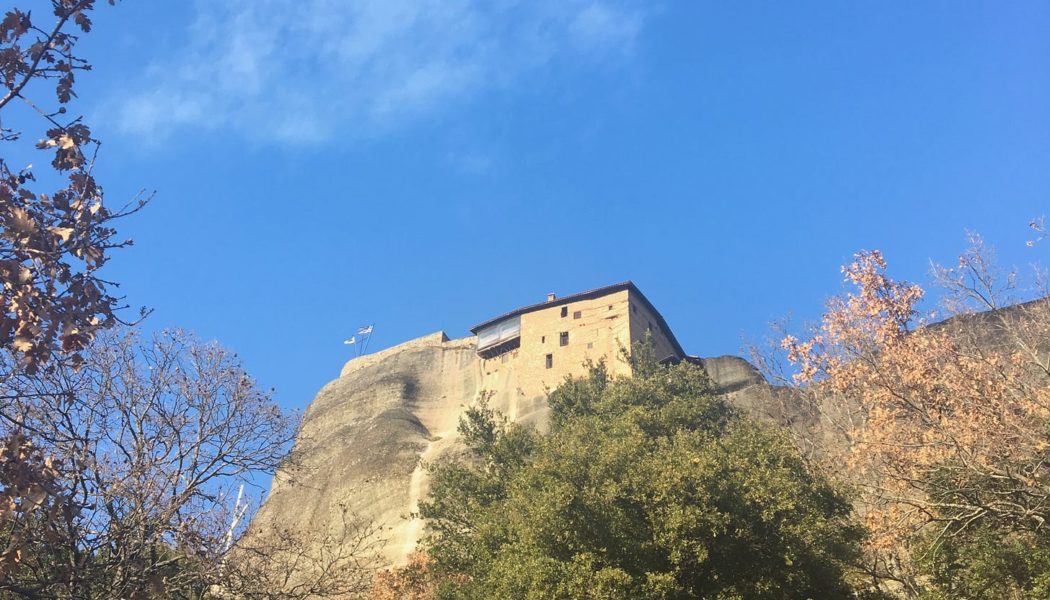

On the last day of the conference, all of the participants made a pilgrimage to the Meteora monasteries. These are built on huge rocks, some soaring over a thousand feet above the valley below. In the fourteenth century, seeking a greater life of asceticism and seclusion from the political and military turmoil of the crumbling Byzantine world, St. Athanasios Koinovitis led his followers to move to these heights. Until the twentieth century, the monks reached them only by the most precarious means: ladders, ropes and pulleys, or handholds burned with strong vinegar into the face of the rock.

It was there that I found that my grandmother’s prediction that I would find the sky in Greece incredible fulfilled—or, more precisely, it was the light. As we made our way up the road to the Varlaam Monastery a sudden shaft of light fell upon us between two of the rocks. In that single momentary beam was concentrated all the glory of the world. A little later, standing on the terrace on the roof of the Monastery of St. Nicholas Anapausas, surrounded by the whole landscape of Meteora, the air around us seemed to be a very ocean of light. I could well understand why one would want to be a monk there. You could spend an entire lifetime just contemplating that light, just looking at it, letting it wash over you. In that place, the prophecy that “the earth shall be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the Lord, as the waters cover the sea” (Habakkuk 2:14) had come true in the awareness imparted by that abyss of light flowing over all things.

One of the most confusing lines in the Nicene Creed for me has always been when we call the Son of God “light from light.” Of course, Our Lord called Himself “the light of the world” (John 8:12) (and He called us to be lights too) and, as the Church does every night, Simeon hailed Him as “a light to reveal God to the nations and the glory of His people Israel” (Luke 2:32). But it always felt out of place that, in the midst of a doctrinal expression of belief in rather abstract terms, we would include this line. Some theologians explain it as a particularly powerful metaphor for the Son’s consubstantiality with the Father: the Father and the Son that proceeds from him are both God, just as both the light in the sun and the light that proceeds from the sun are the same light.

There is indeed a long history of talking this way, rooted in both the Bible and Greek philosophy (especially Plato’s potent allegory of the sun in the Republic) and running through Fathers of the Church like St. Dionysius and St. Maximus, and medieval scholastics like St. Thomas Aquinas and St. Bonaventure. But I’ve never found this explanation entirely satisfying. If it’s only a metaphor, why pick that one to include in the Creed, even if it is a really good metaphor? There are lots of good metaphors, and besides, obvious metaphors seem out of place in what is apparently trying to be a more literal, doctrinal statement.

This is not to devalue metaphors at all. As many linguists have taught us, all language is in some sense metaphorical, calling attention to one thing by intertwining it with something else. And if this is true for normal language, it’s doubly true for theological, spiritual, and doctrinal language, with which we try to express the unutterable mystery of the source and ground of all things that we call God. One can only express that mystery by using language that was first made to talk, even if there also metaphorically, about other things.

But still, that language—and the Church’s pervasive use of language associating light with Jesus, as in the Exsultet at the Easter Vigil or the blessing of candles on the Feast of the Presentation of the Lord—has always struck me as odd. When spiritual masters (and at least some of the fathers at the Councils of Nicaea and Constantinople were surely spiritual masters) use odd language, one does well to pay attention. Something deeper is going on there.

I did not gain deeper conceptual understanding of what it means to call God the Son “light from light” at Meteora; rather, for a few fleeting moments, I saw what the line means. The streaming of light through those rocks from the source of light made present the divine one who is “light from light.” That is why, as I said, it was easy to imagine someone spending a whole lifetime on those rocks. What could be more worthwhile than having the privilege of seeing that light, God made visible, every day of your life?

I made this pilgrimage, I was privileged to see this light, as a Catholic travelling with mostly Orthodox theologians. Any attempt to sum up the splits between East and West are doomed to be tendentiously partial and naïve. But one way of thinking about the split is to conceive it as a split over two ways of perceiving light.

For Westerners, like St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, visible light is a sign of God’s presence. It points us toward God; it is an analogy that refers us to God, and to the other lights God gives, like the lights of grace and faith. God is made present in light as a cause is made present in its effects, or as that which is signified is present in signs, or as the primary side of an analogy is made present in the secondary analogates.

By contrast, for many in the East (like St. Gregory Palamas and those monks that first climbed the rocks at Meteora) light is, at least sometimes, the very presence and activity or energy (ἐνέργεια) of God, God Himself made present to us. Our bodies, including our eyes, can be transformed so that we see God present to us, as God always is in all things. Visible light need not be merely a created sign or effect pointing us to God; it can be an occasion for God himself to be made present to us. What I saw was ordinary sunlight; it was not, so far as I know the light of Tabor which the apostles saw at the Transfiguration, and which the hesychast monks surrounding them. But maybe, in a way, for a moment, I did see that light.

As I always do, I travelled with many books when I went to Greece. On the plane ride over, I re-read St. Gregory Palamas’ Triads and 150 Chapters. I was thereby primed to see according to the Eastern tradition when I got there. But while I was there, I began re-reading the great Italian writer Roberto Calasso’s magnificent retelling of the Greek myths, The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony, and he reminded me that this experience of the divinity in light is an old one in the Greek tradition. On the way back to Athens, we passed close to Aulis, where Agamemnon sacrificed his daughter Iphigenia before setting out for Troy (or, at least, attempted to do so, depending on which version of the myth you’re considering). In Euripides’ telling (as Calasso reminds us), Iphigenia says that “to look into the light is the sweetest thing for a mortal.” For the ancient Greeks, that looking is a tragic, melancholy thing, for soon the light will pass, and one will be left with the eternal, hopeless night of life as a shade in Hades. That tragic, melancholy sense can still be ours today if we set aside the wild hopefulness of Christian vision. I also took to Greece the poems of C.P. Cavafy, the late 19th and early 20th century Alexandrian poet. In “The God Forsakes Anthony,” he describes how, when the divine passes out of one’s life, one can face it with resignation, even with a sort of aesthetic appreciation, despite the fact that one is going to lose the light forever:

When suddenly, at the midnight hour an invisible company is heard going past, with exquisite music, with voices-- your fate that's giving in now, your deeds that failed, your life's plans that proved to be all illusions, do not needlessly lament [...] listen as an ultimate delight to the sounds, to the exquisite instrument of the mystical company, and bid farewell to the Alexandria you are leaving.

There’s something poignantly beautiful about that pagan resignation, that love for the light and longing for life that still has the stoic wherewithal to turn away when one must. In the face of the aesthetic sense possible with that resignation, any expression of the hopefulness of the Christian vision can seem like poor taste, like kitsch. Transfigured Christian perception confirms Iphigenia’s words that seeing the light is the sweetest thing, but not because the Christian knows he must lose that light, but because he can see in the light the very presence of God, the God Who deifies him and makes him no longer mortal. The Christian must give up the aged wisdom of the tragic Greeks with its perfect aesthetic taste, and accept the life of a child, basking always in the light that streams down from the Father of lights.

From this childlike perspective, which eschews polemics, the Eastern and Western views are not opposed. Really, things are both ways—visible light often just is a sign or effect of God (but it thereby really does make God present) and it sometimes just is the very presence of God. In any case, what I carried away from Meteora was a sort of imperative to spend more time looking at light. To say that if we spent more time just gazing upon light, we would have fewer conflicts in the Church or the world, or that we would all be closer to God or kinder to our neighbors sounds, perhaps, ridiculous, like a waste of time, like dismissible hippy spirituality, like a distraction from the real work of building the kingdom of God practically. But I stand by it. I accept the childlike, contemplative vocation that the light in Meteora gave me. The kingdom of God is already present, including in light, and we have the privilege to see it and make it visible to others. The light I saw at Meteora is present everywhere; I have seen it between the skyscrapers in my own city’s downtown, between the ranch houses of my own suburban neighborhood. What it gives is the possibility of a simple vision that can return to the source of all things, and rest.