During a short papal flight from Boston to New York on October 2, 1979, Father Jan Schotte (later a cardinal but then a low-ranking curial official) discovered that Cardinal Agostino Casaroli, the Vatican’s Secretary of State, had done some serious editing of the speech Pope John Paul II would give at the United Nations later that day. Schotte, who had helped develop the text, found to his dismay that Cardinal Casaroli had cut just about everything the Soviet Union and its communist bloc satellites might find offensive – such as a robust papal defense of religious freedom and other human rights. Schotte took the revised, bowdlerized text to John Paul II’s private cabin on Shepherd One and explained why he thought Casaroli, the architect of the Vatican’s attempt at a rapprochement with communist regimes in the late 1960s and 1970s, was wrong to dumb down the speech.

John Paul looked over the marked-up text, thought a bit, and then took Schotte’s advice. Speaking at what the world imagined to be its greatest rostrum, he would make a strong, principled defense of human rights. And if tyrannical regimes were upset by that, too bad.

They were indeed upset, and their unease was palpable to all of us in the General Assembly Hall that day. But embattled Catholics behind the iron curtain were reminded that they had a champion in Rome who was not going to play world politics by the world’s rules. The Pope was going to play by evangelical rules.

Cardinal Schotte’s recollections of that incident, which he recounted to me in 1997, have taken on a new salience, for Vatican diplomacy seems to be reverting to a Casaroli-style accommodation of thuggish regimes. Earlier this month, for example, a Sunday Angelus address in which Pope Francis would express, in the mildest possible way, concerns about the new National Security Law in Hong Kong and its chilling effect on human rights was distributed to reporters an hour before the noontime Angelus. Then, shortly before the Pope appeared, reporters were told that the remarks on China and Hong Kong would not be made after all.

It is not difficult to imagine what happened: a disciple of the late Cardinal Casaroli likely persuaded the Pope to avoid saying anything that could be regarded as criticism of the Chinese communist regime.

In The Next Pope: The Office of Peter and a Church in Mission (recently published by Ignatius Press), I suggest that the institutional default positions in Vatican diplomacy do not reflect two lessons taught by the late 20th century: the only authority the Holy See has in world politics today is moral authority; that moral authority is depleted when the Church fails to speak the truth to power, especially totalitarian and authoritarian power. The truth can be spoken prudently and in charity; but it must be spoken. If the truth is not spoken, the Vatican tacitly confesses its weakness and is always playing defense on a field defined by the enemies of Christ and the Church.

Recent papal diplomacy has constantly stressed the importance of “dialogue.” And yes, “Jaw, jaw is better than war, war,” as Winston Churchill famously said. But Vatican efforts at dialogue that do not begin from the understanding that authoritarian and totalitarian regimes regard “dialogue” as a tactic for maintaining their power are not going to get very far. The current Chinese regime, for example, is not interested in “dialogue” about or within Hong Kong; it is interested in crushing the liberties it swore it would honor after the city reverted to Chinese sovereignty in 1997. To pretend otherwise makes the situation worse. The same cautionary rubric applies to Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Russia, and other systemic violators of human rights.

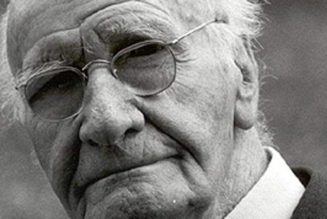

In The Next Pope, I underscore that truth-telling in Vatican diplomacy is also essential for evangelical reasons. In countries that systematically abuse their people, the Church’s mission to proclaim the Gospel is impaired when those people do not perceive the Catholic Church as their defender. Thus the next pope, I propose, should mandate a wholesale reevaluation of Vatican diplomacy in the post-World War II period, bringing qualified lay experts into the discussion. That study must include a thorough, unblinkered evaluation of the Casaroli legacy, which remains a force in the papal diplomatic service and the curial bureaucracy – despite incontrovertible, documented evidence that Cardinal Casaroli’s approach to communist powers failed, and in fact made matters worse.

The Holy See’s moral authority, and the Church’s evangelical mission, are at stake.