(And Then I Wrote…)

Since this site began more than six years ago, every Thursday I have been publishing a reprint from my column “Across the Universe” in the British Catholic journal, The Tablet. I have finally gone through all of them (except for 2019’s columns) and I’ve even re-published a few of the oldest ones that came out here before our readership had grown.

In order to let my backlog build up a bit, I am taking “Across the Universe” offline for 2020. Instead, I am republishing a selection of other articles that I have written an published in various places… often obscure.

This one is not so obscure, and in fact it’s a reprint of a posting here from four years ago… but I thought it would be appropriate to show it again during this season.

How did this article come about? I was invited to write an article about the Magi for the edition of L’Osservatore Romano of Epiphany, which is celebrated this weekend in most of the world, and on January 6 (the traditional day of Epiphany) at the Vatican. I sent them an English text overnight, and they ran it on January 6, 2016… on the front page!

So Father Jim, whom I shout out, and our blog here, became now known to millions…. well, hundreds… of the most important people at the Vatican.

I point out that my article. below, is on the right; the fellow with the gray beard who looks like me is actually an Iranian leader…

Magi or Shepherds? My article, using the wonderful question posed by Fr. Jim, ran on the front page of the Official Vatican Newspaper on January 6

The feast of Epiphany is special to us astronomers. Of all the visitors who came to see the newborn Savior, only shepherds and astronomers are specifically mentioned by St. Matthew. Of course, this fame comes with a cost. Epiphany is also the season when we astronomers are besieged with requests to “explain” the Star of Bethlehem.

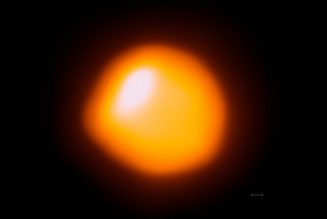

Johannes Kepler famously attempted to identify the Star as a “nova” caused by the conjunction of planets. On October 9, 1604, Kepler had been timing a conjunction of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn; the following night, a bright star suddenly appeared in that part of the sky, between Jupiter and Saturn. Kepler leapt to the obvious, but false, conclusion that the conjunction of planets somehow caused the new star. (We now recognize the new star as a supernova, the last such one seen in our own galaxy. Among other things, this supernova inspired a series of lectures on astronomy by Galileo… which would lead, ultimately, to his first use of a telescope to study the stars in 1609 — the same year Kepler published the first of his famous laws of planetary motion.)

Kepler was prompted to use this supernova to explain the Star of Bethlehem after coming across a book by Laurence Suslyga of Poland that dated the birth of Jesus at around 4 B.C. By assuming that great conjunctions like the one he had just observed would lead to bright “new stars,” he decided to look for such a conjunction at the predicted time of Jesus’ birth. Not surprisingly, he found one.

Nor was he the last. Since then, thousands of amateur scholars have searched tables of conjunctions — and nowadays, computer planetarium programs — to come up with possible explanations. The fact is, there are any number of possible planetary arrangements, or comets, or exploding stars to match any of the (equally numerous) calculations for the true birthdate of Jesus. A recent search for “star of Bethlehem” on amazon.com comes up with 4,396 books and videos available for sale on the topic. And just about every one of them is convinced their argument is the correct one. Without at doubt, most of these explanations — perhaps all of them — are mere coincidences, just as the chance arrangement of planets and supernova in 1604 fooled Kepler.

One book which pointedly does not attempt to give an astronomical explanation is by a fellow Jesuit at the Vatican Observatory, Fr. Paul Mueller, and myself. Instead of arguing over which conjunction works best, we ask a different question: Why does it matter?

We don’t mean that in an impertinent way. It is curious to contemplate what exactly it is about this story that so many generations of astronomers and amateurs have found so fascinating. Part of it may be the hope that science can “prove” the Bible to be true; a false hope, since speaking as a scientist myself I know how tenuous such proofs can be. (Nor would I trust any religion simply because science had “proved” it.) But part of it must be the link between the glory of the stars at night and the glory of the Savior among us. That, I am confident, is the connection that Matthew was trying to make.

Indeed, my experience as a scientist makes me approach the Magi story with a completely different set of unanswerable questions. What made the Magi travel so far from the comforts of home? What were they looking for, really? Seeing the motivations behind many of my fellow scientists, I can easily believe that the Magi could have been moved by a mixture of motives, both profound and profane. Maybe they were trying to test the accuracy of their astrological predictions. Maybe they were looking to get away from an irritating boss, or an unhappy home life. Maybe they were looking for a king worthy of their worship.

Another mystery to me is, how did they finally recognize Jesus when they found him? Then, as now, folks immersed in scholarship can stereotypically be less tuned into the realities of ordinary life… at least in my case, one baby looks much like another. And yet they knew to leave their gifts with a poor child in a manger.

And perhaps the most important part of the Magi story has nothing to do with the star itself. After having left their homes, for whatever reasons, and after encountering the one whom they recognized as a king, they did a most unexpected thing: they returned home. Back to that irritating boss, or that unhappy home life. Back to those tedious astronomical calculations. Back from their search for a king, even after they had found him. But, as Matthew tells us, they went back by a different route. The encounter changed them. But it did not change their life or work, or the way they discovered the truth.

The “wise men” were scholars, just like the scholars who work today at the Vatican Observatory. But scholarship is not the only route to the truth. Shepherds also discovered the infant in the manger. They were inspired by the songs of the angels. (Oddly, no one asks shepherds today for an “explanation” of those songs!)

Fr. James Kurzynski, a priest of the Diocese of La Crosse, Wisconsin, recently wrote about this contrast on the Vatican Observatory’s blogsite, www.vofoundation.org/blog. He is himself both an amateur astronomer — a wise man — and a pastor, a shepherd of souls. And at the end of his reflection he asks his readers, “How do you come to truth? Are you one of the “Magi,” gravitating toward natural reason? Are you a “Shepherd” who is compelled by Divine Revelation? Or are you a little bit of both?”

The story of the Magi inspires us to look at our own journey. What are we looking for? Why do we look? How do we know it when we find it? And are we brave enough to return home with it, once we have found it?