The two longest passages in the New Testament that have questionable origins are the longer ending of Mark (16:9-20) and the section on the adulteress in John’s Gospel (7:53-8:11). Interestingly, both passages are twelve verses long.

We’ve already discussed the longer ending of Mark, and here we take up the story of the adulteress.

In scholarly circles, it is known as the Pericope Adulterae (from Greek and Latin roots, meaning “the section on the adulteress”; note that pericope is pronounced per-IH-kuh-PEE).

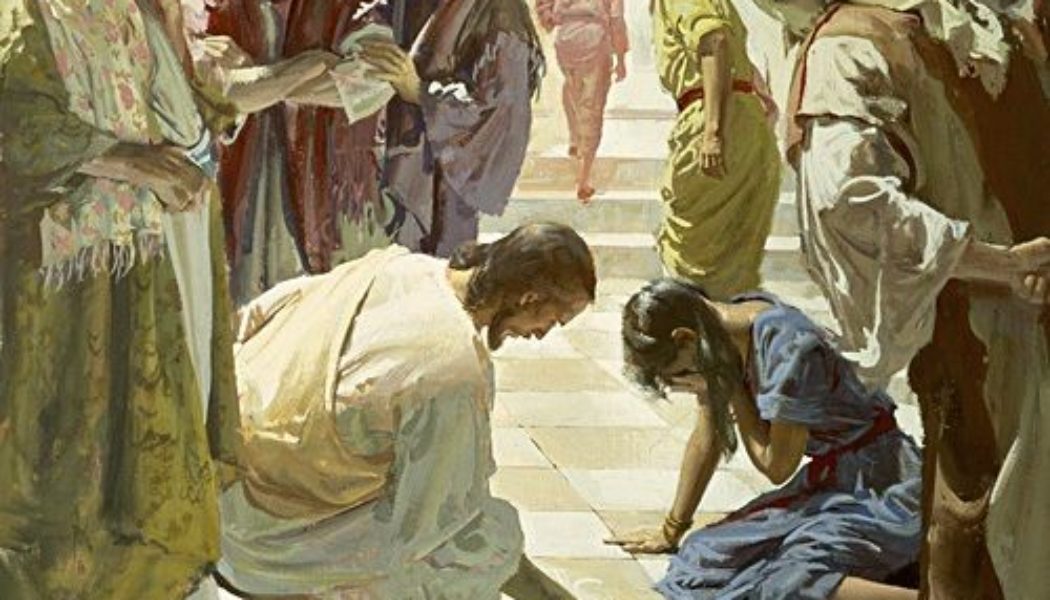

In the story, a woman caught in the act of adultery is brought before Jesus, and his opponents test him by asking what should be done with her. The Mosaic Law prescribed death for such offenses (Lev. 20:10, Deut. 22:22), but Jesus says, “Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone at her.” The opponents then disperse, and afterward Jesus tells the woman to go and sin no more.

It’s a vivid, memorable story, and many people know it today.

So why would anyone question it? The first reason is that it is not in many of the early manuscripts. The New Testament was written in Greek, but the pericope is not found in any surviving manuscripts before Codex Bezae, which dates to the A.D. 400s. This is significant, because John was one of the most popular Gospels in the early centuries—as evidenced by the surviving number of copies of it—and we would expect the pericope to be in other early copies if it was part of the original. The pericope also is missing from some early Latin, Syriac, and Coptic manuscripts.

The second reason the pericope is questioned is that it floats. That is, when it does appear, it’s found in different places. Sometimes it follows John 7:52, sometimes 7:36, sometimes 7:44, sometimes it’s tacked on at the end of John’s Gospel (after 21:25), and sometimes it’s at the end of Luke 21 (following 21:38). This reflects the behavior of scribes trying to fit it into the Gospels and being unsure where to place it.

The third reason is that none of the Greek commentators mention the passage before Euthymius Zigabenus, around A.D. 1118. Although this is an argument from silence, a silence of more than 1,000 years is striking and could suggest that most of these commentators were unfamiliar with the passage.

The fourth reason is that the style of the pericope differs from John’s Greek style. Experts indicate that it doesn’t sound like him. Instead, it sounds more like Luke’s Greek style. However, arguments from style are not particularly strong, and it’s always possible that an author is closely following an earlier source that had a different style.

For the above reasons, most contemporary scholars hold that the pericope was not originally part of John’s Gospel but was added to it at a later date. Consequently, many contemporary Bible translations put the pericope in brackets and have a footnote discussing the issue of its origin.

However, scholars also acknowledge that there is evidence that the story is ancient. The fact that the style is said to sound like Luke and that it is sometimes placed in Luke’s Gospel has led some to suggest that it may have actually been penned by Luke rather than John.

Further, the early second century writer Papias of Hierapolis—who was gathering his data at the end of the first century—may have mentioned the story. In the 300s, the historian Eusebius stated that Papias “has set forth another story about a woman who was accused before the Lord of many sins, which is contained in the Gospel according to the Hebrews” (Church History 3:39).

Some have thought that this may be a reference to the Pericope Adulterae, but this is not certain. While it could have appeared both in John (or Luke) and the Gospel of the Hebrews, if it was the same story, we’d expect Eusebius to refer to it as being found in one of the canonical Gospels. Further, the pericope involves a woman accused of one sin—an act of adultery that she was caught during—not a multitude of sins.

Still, it is possible that this is early evidence for the existence of the story, if not its placement in a canonical Gospel.

Of the arguments against the pericope’s originality to one of the canonical Gospels, the strongest is its absence in early Greek manuscripts. What could explain this?

One possibility is that—after John (or Luke) wrote the passage—an early, influential scribe left it out of his copy, and this affected the copies that followed. That would explain why later scribes weren’t sure where to reinsert it, and it would explain why Greek commentators didn’t mention the passage for so long. The only remaining argument is stylistic in nature, and we’ve mentioned that stylistic arguments tend to be inconclusive.

The major question would be why an early, influential scribe would omit the passage. While scribes do occasionally omit part of a sentence or a verse by accident, the omission of 12 full verses looks deliberate. So what would the reason be?

A key proposal is that it has to do with the subject that the pericope involves: the forgiveness of adultery.

Adultery was regarded as a particularly heinous sin, and some early Christians believed that a person could be sacramentally forgiven of it only once after baptism. Others believed that it required a very lengthy period of penance before reconciliation. And some thought that it could not be forgiven at all.

Around A.D. 220, Tertullian of Carthage was of this view. “Such [sins] are incapable of pardon—murder, idolatry, fraud, apostasy, blasphemy; of course, too, adultery and fornication” (On Modesty 19).

Around 251, St. Cyprian of Carthage wrote that “among our predecessors, some of the bishops here in our province thought that peace was not to be granted to adulterers, and wholly closed the gate of repentance against adultery” (Letter 51:21).

Given the early stage of doctrinal development, the Pericope Adulterae—in which Jesus simply says to the adulteress, “Has no one condemned you? . . . Neither do I condemn you; go, and do not sin again”—could seem shocking and in conflict with what they otherwise believed about forgiving adultery.

Consequently, there could be a motive for early, influential scribes to remove the passage—presumably thinking it had been added by an earlier scribe who was lax on the issue of adultery.

The nature of the passage may also have made some commentators reluctant to discuss it for the same reason.

If the Pericope Adulterae was not originally in one of the Gospels, what is its status as part of the Bible?

A footnote in the New American Bible: Revised Edition states, “The Catholic Church accepts this passage as canonical scripture.”

The basis for this statement is that the Council of Trent infallibly defined that the books of the Catholic canon are “sacred and canonical, these same books entire with all their parts” (Decree Concerning the Canonical Scriptures).

This affirmation is most clearly directed against the views of Protestants who wanted to consider the deuterocanonical portions of Daniel and Esther to be non-inspired.

There was some discussion at the council of the Pericope Adulterae, but the fact that the final decree does not make it clear which “parts” of biblical books it has in mind—beyond those of Daniel and Esther—could be seen as leaving the matter not fully settled.

However, even if the passage was not original to the Gospels, it still may have been written in the apostolic age and could count as inspired scripture.

And even if this were not the case, the passage teaches nothing contrary to the Christian faith. Early authors who were skeptical of forgiveness for adultery were mistaken, and this passage provides a dramatic, memorable illustration of a truth of the faith:

There is no offense, however serious, that the Church cannot forgive. There is no one, however wicked and guilty, who may not confidently hope for forgiveness, provided his repentance is honest. Christ who died for all men desires that in his Church the gates of forgiveness should always be open to anyone who turns away from sin (CCC 982).