The natural affinity between evil and bureaucracy

August 22, 2023 by Amy Welborn

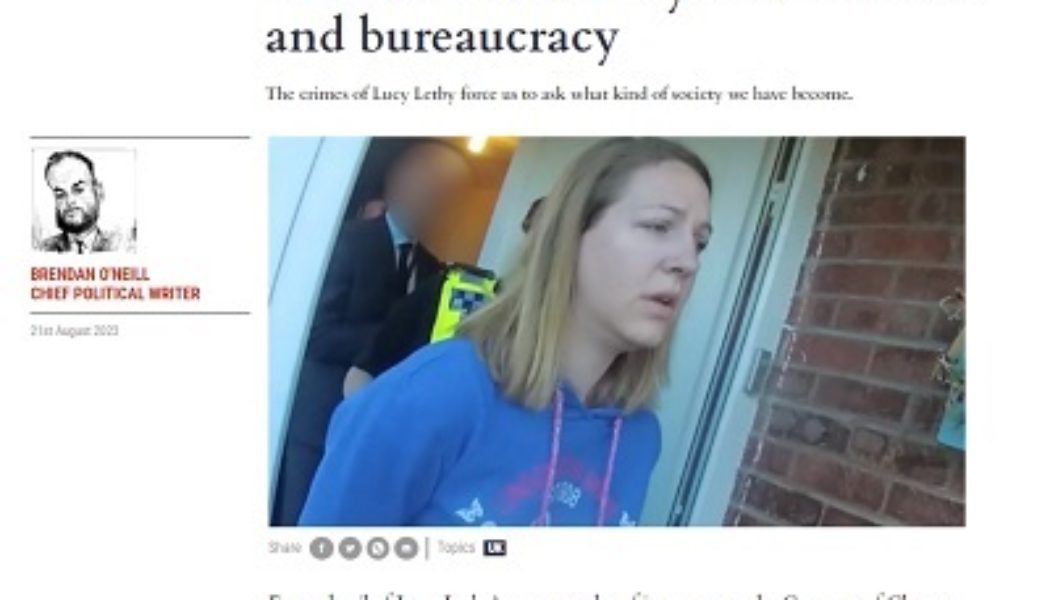

Across the pond, in England, one of the major news stories of the past week has been the conviction of Lucy Letby to life in prison:

Nurse Lucy Letby will spend the rest of her life behind bars for killing seven newborn babies after a judge on Monday ruled Britain’s most prolific serial child killer of modern times should never be released.

Letby, 33, murdered the five baby boys and two baby girls at the neonatal unit of Countess of Chester hospital in northern England over 13 months from 2015, injecting the infants with insulin or air, or force fed them milk…

….She was found guilty last week of seven counts of murder and seven of attempted murder following a 10-month trial at Manchester Crown Court. Jurors were unable to agree on whether she had tried to kill six and acquitted her of two other charges of attempted murder.

You can read much more at the link or any of the other dozens of articles written about the case through a search.

In the wake of the conviction, the question of cover-up and protection has arisen with great force. Doctors and others who for years suspected Letby’s role in these suspicious deaths are coming forward claiming that they were discouraged from making their concerns public – or even threatened with punishment for doing so and forced to apologize to Letby for their suspicions.

The always excellent Brendan O’Neil at Spiked takes this on – and as you read, it shouldn’t be difficult to apply his argument to other contexts:

It is almost unimaginably Kafkaesque. In fact, the bleakest literary mind would struggle to conjure such a scene. Doctors rightly concerned that they had a mass murderer in their midst being told to plead for the forgiveness of the woman they suspected of murder. A nurse unwittingly being garlanded with official recognition of her ‘upset’ after she had inflicted upset of the most unholy variety on family after family. A child-killer being genuflected to by child-savers at the behest of oblivious bureaucrats. If Britain remains a civilised society, it owes it to itself to explain this most morally distorted of acts where managerial elites unwittingly sided with evil over good. Something has gone horribly wrong in the bureaucracy when such a grave moral inversion can occur…

…

The cry of our times is ‘Listen to the experts’, yet we now see what a shallow slogan that is. For in this case, this life-and-death case, the experts seem to have been cold-shouldered, even mistreated. Noticing an unusual number of deaths on the ward, and noticing that Letby was the only nurse who was on duty for every one of those deaths, the truest experts at the Countess of Chester, the doctors who have devoted their lives to saving the prematurely born, gave voice to their suspicions. And they were shot down, every time. Not only were they forced to write a letter of apology to Letby – two consultants were also ordered to attend a mediation session with her. In early 2017, doctors were told that Ms Letby’s parents were threatening to refer them to the General Medical Council. Again, it’s Kafkaesque: good medics forced to undergo a kind of technocratic therapy with the woman they suspected of mass murder, and then warned of GMC ramifications if they kept asking questions about her.

The most damnable thing is the question of why management behaved in such a seemingly distant, blinkered fashion. Two consultant paediatricians at the Countess of Chester allege that, in July 2016, the hospital refused to contact the police over the rise in baby deaths because executives were concerned that such a course of action would ‘damage the hospital’s reputation and turn the neonatal unit into a crime scene’. Reputation. There it is, the overriding concern of the bureaucrat, the organising principle of technocracy: to protect the institution’s reputation at all costs. ‘You are harbouring a murderer’, doctors warned managers at the Countess of Chester, and it appears management’s response was to worry about reputation…

…

It speaks to the rise and rise of bureaucracy for its own sake. Bureaucracy designed not to get things done but to replicate itself, and its influence and control. Such a detached entity of power, which sits above expertise, morality and reality itself, is likely, at some point, not only to be blind to the interests of the public, but also actively hostile to them. It is possible that this is what has been exposed by the Letby horror: the existence of a self-replenishing class of post-moral functionaries who unthinkingly elevate their prestige above everything else. Just as the police’s slowness in solving the crimes of the Yorkshire Ripper forced a reckoning with the misogyny and classism of the 1970s elites, so the failings at the Countess of Chester will surely make us contemplate the characterless, agnostic style of the technocratic regimes that replaced civil society as we once knew it.

There will no doubt be a rush to find out why Letby did what she did; to uncover some childhood trauma that ‘turned her into a killer’. This social-constructionist obsession with the pained origin stories of mass murderers speaks to the moral immaturity of our times. The truth is that evil has no meaning. It is anti-meaning. As the great Marxist critic Terry Eagleton wrote in On Evil, it is ‘supremely pointless. Anything as humdrum as a purpose would tarnish its lethal purity.’ Evil’s ‘negativity’ is one which finds ‘positive existence itself abhorrent’, he wrote. Indeed. That neonatal ward was full of meaning. There was meaning in the doctor’s life-saving efforts, in the loving and longing of the waiting parents. There was the meaning of life itself. Letby’s evil was to poison this haven of meaning, this gathering of moral purpose, with pure and pointless wickedness.

Evil has a ‘natural affinity with the bureaucratic mind’, wrote Eagleton. ‘Flaws, loose ends and rough approximations are what evil cannot endure’, he wrote. ‘Goodness, by contrast, is in love with the dappled, unfinished nature of things.’ This, I believe, is what we saw in Chester: an association, however unwitting, however regretted, between the bureaucratic mind and the evil mind, with goodness silenced.

It is the challenge of every institution or organization, even if the issue at hand is not something as heinous as murder – or, in case you’re thinking what I’m thinking – sexual abuse.

The challenge? For any human entity to accept its humanness – and the very common dynamics to which all human entities are prone. The dynamic which O’Neil describes above: to allow original mission and purpose to be subsumed to the causes of self-preservation and yes, reputation.

What’s the antidote? Awareness of this dynamic and a resolute refusal to live in denial of it, and yes, rules. Rules that are the same for everyone, consequences that are the same for everyone, accountability to some sort of disinterested parties and a willingness to take the hit, institutionally, for the sake of the good.