The Gospels for the Third, Fourth and Fifth Sundays of Lent can vary (though not this year). Because Lent is the immediate period of preparation of catechumens for Baptism at the Easter Vigil, the Church always allows the use of the so-called “scrutiny readings” — readings specifically chosen for their use in catechumenal preparation — on those Sundays. They also happen to be the readings specified for Year A — when Matthew’s Gospel predominates — and thus are the readings for this year. In Years B (Mark) and C (Luke), there are alternative readings available for these three Sundays. The three sets of scrutiny readings focus on Jesus as the “Living Water” (3rd Sunday), the “Light of the World,” (4th Sunday) and “the Way, the Truth, and the Life” (5th Sunday).

Today we hear the encounter (taken from John) of Jesus with the Samaritan woman at Jacob’s Well.

Jesus arrives in Sychar, about 40-45 miles north of Jerusalem, en route to Galilee. The distance could have been light years, because this is Samaritan territory, and Jew and Samaritan were at loggerheads over many things, including — as the Gospel today suggests — where was the center of worship. (Remember that good Jews in Jesus’ day might make several annual pilgrimages to Jerusalem.) Jews considered Samaritans foreigners at best, perhaps mixed half-breeds following the Babylonian Exile. They regarded Samaritanism as a corrupted, syncretistic religion that pretended to be Jewish. So there is no love lost between these peoples.

“It was about noon.” Noon — when the sun is at its zenith and temperatures roiling — is not the time most people would have been out drawing water. They would have been seeking indoor shelter. So the fact that this woman is out suggests she is also something of an outcast or misanthrope: either she doesn’t want to meet people or them her or both.

Jesus not only sees her, he asks her for a drink. Knowing the animosity between Jew and Samaritan, that completely dumbfounds her. Jesus refuses to entertain her objections, but even tickles her curiosity by speaking of “living water.”

Now the Samaritan Woman is still thinking in purely earthly terms. “Living water” might mean a bubbling spring, and this guy doesn’t even have a pail. “Where can you get this living water?”

Jesus, building on her curiosity begins to speak of a spiritual water that quenches every thirst. The Samaritan Woman still earthbound, hopes this thirst-quenching water might be a labor- (and face)-saving device to keep her from having to return to draw at Jacob’s Well.

Jesus is willing to give her this spiritual water, but elicits her conversion. “Go, call your husband, and come back.”

Equivocating, the woman answers, “I do not have a husband.” Jesus does not let her persist in her half-truth: “You are right in saying, ‘I do not have a husband.’ For you have had five husbands, and the one you have now is not your husband.”

Jesus does not accompany her with accommodation of her situation. He accompanies her with the truth, truth that forces her to admit he is at least “a prophet.” Now she is baffled: “Our ancestors worshipped on this mountain but you people say the place to worship is in Jerusalem.”

Jesus overcomes that division. “The hour is coming” to worship God in spirit and truth. When she offers, “I know the Messiah is coming,” Jesus tells her what — after seeing his Messiahship last week he ordered his apostles to silence — “I am he, the one speaking to you.”

The Samaritan Woman returns to her village and pricks the interest of her people, who come to hear, see and even believe in Christ. Like Andrew with Peter, like Philip with Bartholomew, she is the conduit, the nexus that brings others to the “Living Water” of Christ’s Grace. Because the Living Water Jesus promises is his Grace, the life-giving water of the soul that makes us pleasing to God and heirs of his Promise. To worship God in “spirit and truth” demands worshiping him in grace — the grace Christ came to bring.

It is that grace that catechumens are preparing to receive in sacramental fulness at the Easter Vigil. It is that grace that Catholics seek to renew and augment in their souls through their prayers, fasting, almsgiving and recourse to the sacraments during Lent.

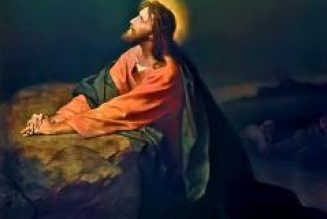

Today’s Gospel is depicted in four paintings by the early 20th-century Polish artist, Jacek Malczewski (1854-1929). These four paintings, “Chrystus i Samarytanka” (Christ and the Samaritan Woman), date from 1909-1912. At least the 1909 painting is held by the Museum of the Archdiocese of Warsaw. One commentator insists that these four paintings are not four successive attempts to capture the scene, but rather four stages in the conversation between Jesus and the Samaritan Woman. For the other three paintings not depicted above, see here, here and here.

Malczewski combines two times: Jesus’ and his own. Indeed, Malczewski uses himself as a model for Jesus. Jesus is attired more in early 20th century rural traveling clothes than first century Israelite garb. He carries a traveling hat and a walking cane, not the usual Israelite staff. Malczewski’s Samaritans (he uses different women in the paintings) are also early 20th century Europeans, not first century Samaritans. Their bare arms and/or revealing necklines would not have been Near Eastern clothing for women of Jesus’ time, though they may suggest that this woman’s multiple men and slinking to Jacob’s Well at noon had something to do with her sexual precocity. The lush surroundings around the Well are a Kraków garden.

In the 1909 painting, depicted above, Jesus asks for a drink. That he looks at us rather than her suggests something of the universality of his request, as the commentator cited above notes. The woman, with two buckets, is surprised, curious and in some sense proud: she has an advantage over this bucket-less Jew.

But the question serves to open a broader and deeper discussion. In the second painting, we see a tired woman (who’s managed a trip to get her hair dyed) staring into the well, reflecting how her life might be easier with this “living water” about which her curiosity has been piqued. In the third painting, she is clearly satisfied with what she hears, with a dreamy look on her face even as her bucket and jug are ready. In the last painting, sitting on the well wall, she is clearly contemplating everything she has heard from Jesus — things she understood (especially about her life) and things she didn’t — but clearly recognizing he is a “prophet” if not the “Messiah.”

Interestingly, in all four paintings, Malczewski’s Jesus keeps his eyes fixed in the viewer’s direction.

Malczewski was part of the “Young Poland” (Młoda Polska) movement in art, which was prominent in the late 19th and early 20th century. By the time Malczewski was painting, Poland had been wiped off Europe’s maps for more than a century, occupied (“partitioned”) by Russia, Prussia and Austria. Efforts to recover independence — from attaching national hopes to Napoleon to two bloody but failed Uprisings — had led in the late 19th century to a conviction that, Poland’s political status notwithstanding, it was imperative to keep Poland alive through its culture. Hard work and artistic achievement would preserve something of Poland that politics could not. That’s why the designs on the dresses of Malczewski’s Samaritan Women reflect some degree of Polish folk design.

[By the way, let me add one more painting of Christ and the Samaritan Woman somewhat in Malczewski’s vein of depicting the scene in a more contemporary European setting, but painted roughly a few decades before him. Henryk Siemiradzki (1843-1902) painted this more traditional but European depiction of the scene. I share it because it hangs in the Lviv National Gallery of Art, which means it is exposed to destruction at the hands of vandalic Russian aggression.]