Day is fled and gone,

life too is going,

this lifeless life.

Night cometh,

and cometh death,

the deathless death.

John Henry Newman / Bishop Andrewes

Midway through her life, my mother became fascinated with genealogy. Since I’ve always been adept at research, I helped her search for connections, and along the way developed an interest in it as well. As computers and online newspaper archives and Ancestry.com entered the picture, the family tree exploded. We made new connections. Found records that were previously inaccessible. Pushed the timeline back hundreds of years. Put out new branches. Along the way, we found some delightful surprises, some moments of pride, and some very very dark corners.

For a long time, one thing about my mother’s (and my own) pursuit of the subject puzzled me: our family didn’t get along. Some of the silences lasted for years, some for decades. There were feuds that endured for a lifetime. One of her brothers (the one who sued her) was dead for years before we even found out. I myself went for long periods without speaking to her. No one holds a family grudge like the Irish.

Why would someone with a dysfunctional family pour so much effort into building a family tree? If you can’t love the people who are alive, why bother searching for dead people to love?

Of course, the question answers itself: you’re searching for people to love, for a connection–hanging on to some slim reed of the notion of family. Maybe if you collect enough of those reeds–enough birth and death certificates, faded photos, grainy newspaper clippings–you can bundle them together into something akin to a functional idea of “family.” Maybe you can lay a finger on the moment in the past where things went wrong. Maybe it was when she eloped with him, or they moved to a new state.

And no one is easier to love than the dead. They can’t disappoint you or betray you. Those old photos are endlessly ductile. That old man’s eyes seem devilishly winsome in the only remaining photo, when in reality he was just devilish. That child learning to ride a bike still has a choice of paths ahead of him, one of which might not lead to an early grave.

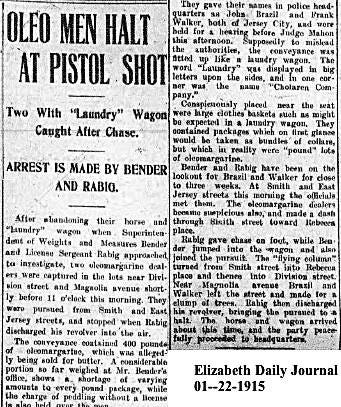

Naturally, that’s not the only–or even the main–impulse of genealogy. Normal people come at it from the exact opposite direction–they love their family so much they want to know as much as possible. They’re proud of their roots. Proud of how far they’ve come. In our time of searching, we found plenty to be proud of, so those were the things we focused on. My mother’s memory of her grandfather–the first bicycle cop in Elizabeth, New Jersey–was colored by many things, not least his bad ending. But finding newspapers articles about his colorful exploits–halting a butter counterfeiting ring or arresting the actor Stepin Fetchit on a drunk and disorderly–added new light to sad memories.

Did it heal anything? To a degree, yes. Memory is plastic. It can be changed. Augustine observes, in a letter to Nebridius (Epist. 7), that as we add new things to memory, we see old things again in a different way.

Memory is not fixed. Don’t you have a memory that once caused you acute pain, and then ten years later just a twinge of shame, and another ten years later only a bittersweet regret? The memory is a marker for a fixed point in time and space, but you are fixed in neither time nor space. The memory is a single beat in a story that continues to unfold. Every human is the ship of Theseus, all our parts continually replaced.

Eventually, we come to the realization that Proust did, finding ourselves “still reliving a past which was no longer anything more than the history of another person” (A la recherche du temps perdu). And yet that history trails out behind each of like a kite’s tail, and like that tail, it can steer and stabilize us, or send us vectoring into the ground.

For a long time, we stopped work on the family tree. I turned up too many suicides, too much mental illness, too much darkness. And then I found the archives of the Elizabeth Daily Journal, and delightful stories like this:

And suddenly the broken, damaged man of my mother’s memory was alive again as a vital and heroic person who helped prevent oleomargarine from being sold as butter in the city of Elizabeth in 1915. The memory of him was still in shadow, but we’d opened the blinds and let in a bit of light. That changed her. She would bring it up for the rest of her life.

Eventually, the last person who knows our voice, our face, our touch will die, and the living memory of each one of us will vanish from the earth. When she died two years ago, the memory of my great-grandfather’s voice disappeared forever. But all of us leave some trace behind, and we have a duty to the dead not to let that disappear.

I remember one of the endless donnybrooks in my family over something stupid–I can’t even recall what. I said, Haven’t you ever made a mistake? She didn’t miss a beat: I made four of them. I didn’t need any explanation: she meant marrying my father and having three children. One, two, three, four. Got it, mom. I can count.

It was hardly the worst thing she’d said in a lifetime of saying inexcusable things, but that one sticks with me because of what it suggests–a lifetime of regret. Bad choices. Wrong paths. She’d said similar things before, but once that moment had passed, I just felt an immense pity for her. Even later in life, when she had mellowed a bit and we made peace, she would admit that she regretted having a family. She had wanted to be the single maiden aunt spoiling nieces and nephews.

I was mature enough at that point to not take it personally–and hey, I already existed, so that barn door couldn’t be shut. I knew she loved me to the extent she was capable. That extent was somewhat limited, and maybe she knew that. But if she had been given the choice to do it all over again–marry, build a house in the suburbs, have kids–I knew that she wouldn’t. She loved her grandchildren and great-grandchildren, but I know this in my bones. She said as much.

I’ve let this all unspool at some length because it stands as background to my main point, like a stage flat in a play. Each faith is planted in unique soil. It germinates or withers, but none is like another. Great faiths have grown in the most barren soil, and poor ones in the richest. Indeed, Jesus calls us to be grafted unto Him as the vine, and vines often thrive in hostile environments. My soil was indifferent. I would not call it “hostile.” I’ve encountered worse, believe me. But it was mine, and my faith–the only faith I truly understand–grew there. And here we come to the point of this story.

I don’t talk about my personal mystical experiences because if they could be conveyed in words then they wouldn’t be mystical experiences, but I can get in the ballpark. It was during my return to the faith, which came after a serious medical problem that left me disabled for a time. My mother did something cruel, and although I’ve never had as strong a Marian devotion as some, I prayed a prayer, spontaneously—Blessed mother, be mother to me.

And she was there. I felt it. I felt a mother’s love and comfort in a way I had never known. It was peaceful. It was subtle. But it was real. And it has never left me.

Let’s fast-forward about twenty years. As a deacon and hospital chaplain, I visit the sick every week. I have to be vague here for privacy reasons, since patients sometimes pour out their hearts in those situations. There’s so much pain, and the most important thing any of us can do is not offer advice (most advice is bad) or solutions (they rarely exist) but to simply be a listening heart. Just have a willingness to sit still and listen. There’s nothing unique about my experience. Anyone in ministry could tell you a hundred similar stories. The only thing I bring to the table is a willingness to let the Spirit do His work, while I try to stay out of the way.

Many times, they tell the story of their suffering, and since some are drawing near the end, they need to know it all made some kind of sense. Their story is almost like a seed they need to plant in the mind of another person, and if that person is a stranger, then so much the better.

Of course, I bring the Eucharist for them. We talk about how in suffering we are very close to the cross, that Jesus saved us through suffering, and eventually we all share in that cross. As Paul writes, I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I complete what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions.

We don’t get very deeply into theological waters. It’s not catechism class. It’s a human being in need of comfort, connection, hope, peace. One patient, barely able to speak but obviously angry, asked “Where’s Jesus?” I said Right here, with you on your cross. The patient nodded and relaxed. Jesus was also there in my pyx, so I provided a very tiny piece of Eucharist, held their hand, and they fell asleep.

People don’t need All The Answers of Life and Death. They need to know that others are there for them, but more importantly, that Jesus is there with them, and shares their pain. Most of all they need hope. Christian hope. A sure and certain hope of the resurrection to eternal life.

Once, the story was about patient’s mother, and the heavy weight the patient carried from abuse and neglect. It was all the patient could think about. I related a little bit of my experience, and suggested that the patient has a perfect mother who loves without end, who knew suffering intimately, and who was always close by. I offered my prayer: Blessed Mother, be mother to me. It all fell into place at that moment. There was a lot of crying, so I came back later to check in, and I knew that Mary was there with the patient, giving comfort. The weight was gone. She who knelt at the cross and cradled the battered body of her own child was there cradling that suffering patient. She is mother to us all.

In that moment, someone needed a mother, so Jesus sent His mother to provide a particular kind of comfort that even He–the Logos, the eternal Word–could not provide. A mother’s love.

The fundamentalist preacher John MacArthur once said that Mary has not heard any of the billions and billions of prayers to her, has not in fact hear anything since she died. This is the ignorant lie of a very foolish man.

The dead hear us. They are all around us. That’s what the communion of saints is. It is the entire church, living and dead. The church is an equal opportunity institute. We don’t kick people out just for the trivial reason that they are dead. We realize that some of them are cut off from us forever in hell. Some of them need our prayers as they travel toward sanctification in purgatory. And some of them are right now gazing in love and wonder at our Lord, while also looking upon those they love.

We call that last group the saints. If we are very sure the person is in heaven, we even give them some fancy capitalization, and call them Saints.

And the Saints are here for us.

Bless the Lord, you servants of the Lord,

sing praise to him and highly exalt him for ever.

Bless the Lord, spirits and souls of the just,

sing praise to him and highly exalt him for ever.

Daniel 3:85-86

I slept in the room with my father while he was dying. It was about ten days. He was on a hefty dose of morphine, and was seldom conscious. One day, however, he woke up and was suddenly alert. It’s called terminal lucidity, and it’s a great gift to many who are dying. Some people have a final rally—a momentary hyper-clarity.

With my father, the face which was slack and blank, the eyes which were unfocussed, suddenly all snapped into action as he stared into a corner of the room and grinned from ear to ear. “What are you smiling at?” we asked.

“All of them,” he replied.

Later, I asked the hospice nurses if they had ever seen anything like that.

“Oh, all the time,” they said.

Another case: I was visiting a patient in the hospital, and they said a spouse who had died long ago was there in the room, but the family didn’t believe it was real. What did I think? I said if you see your spouse in the room, then your spouse is probably in the room. Is their presence comforting? Very was the reply.

It’s more common than you think. I have to add that the patient appeared extremely clear and lucid, and the nurses didn’t seem to doubt or think it was an hallucination. “There’s nothing in the church against believing that?” the person asked? “Absolutely nothing,” I replied. In fact, church history is full of similar accounts, including one of the earliest martyr accounts: that of Felicity and Perpetua.

Prior to their execution in Carthage on March 7th 203, Perpetua experienced a vision of her dead brother.

I beheld Dinocrates coming forth from a dark place, where were many others also; being both hot and thirsty, his raiment foul, his color pale; and the wound on his face which he had when he died. This Dinocrates had been my brother in the flesh, seven years old, who being diseased with ulcers of the face had come to a horrible death, so that his death was abominated of all men. For him therefore I had made my prayer; and between him and me was a great gulf, so that either might not go to the other.

She prayed for her brother every day and night, that he may be released from this torment. It is interesting that the language clearly evokes the story of Dives and Lazarus, suggesting the impossibility of Dinocrates getting any relief in the afterlife. Nonetheless, Perpetua continued to pray for him.

Days later, she had another vision, in which he is renewed and released from this torment. It is a powerful early witness to the connection between the living and the dead. Diocrates was in purgatory. The prayers of his saintly sister helped lift him into heaven.

Gregory the Great tells a similar story of the deacon Paschasius appearing to the Bishop Germanus to ask for his prayers so he may be freed from purgatory. I could fill WeirdCatholic.com with similar stories, and Jimmy Akin could add many more.

There is a veil between our world and the next, but the veil is thin, and the Saints, of which Mary is the foremost, are crowded around the throne of majesty, gazing upon on the Lord, gazing upon us.

This post has meandered much like memory does. Part of that comes from my current immersion in Augustine and Proust, but part is also an attempt to thread together a number of subjects: family, suffering, memory, Marian devotion, time, mothers, prayer, mystical experience, intercession, the communion of saints. And all of them do knit together into something more than themselves–into life as it is lived, in this world and the next, but also life as it is perceived, which is not always the same thing.

We are alive. And, paradoxically, the dead are alive as well. They are alive in Christ. They crowd around us, an invisible host looking, Janus-like, upon heaven and earth.

That’s what the title, taken from Newman’s The Devotions of Bishop Andrewes, refers to: our deathless death. Death is not nothing. Death matters. It can shatter the living into million little pieces. But it is also a birth into a new way of being as we, God willing, enter the communion of saints. The grass withers, the flower fades, but in Christ we are born anew to live forever, standing before the throne and praying for all the faithful.

Near as is the end of day,

so too the end of life:

We then, also remembering it,

beseech of Thee

for the close of our life,

that Thou wouldest direct it in peace,

Christian, acceptable,

sinless, shameless,

and, if it please Thee, painless,

Lord, O Lord,

gathering us together

Newman/Andrewes