There are tons of theories surrounding J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and, more broadly, the fictional world of Middle-Earth in which the books take place. One of these theories is that Middle-Earth is actually not a fictional world at all, but our own Earth in prehistoric times, before — as historian Dan Carlin recently put it in his podcast Hardcore History — “the so-called Age of Man began.”

This theory has been around for a while, but it’s unclear where it originated from. It’s possible this theory can be traced back to Tolkien himself, who once said he created Middle-Earth to provide England with a mythology that could compare to those of the Greeks or the Icelanders. The theory gained traction after a public lecture at the University of Oxford in 2022, titled “On Hobbits and Hominins.” During the lecture, Victorian literature professor John Holmes, alongside archeologists Rebecca Wragg Sykes and Tom Higham, debated how the various races of Middle-Earth — men, elves, dwarves, orcs, and hobbits — could be taken as analogies for the various hominin species that once coexisted on Earth.

Even if Tolkien helps us conceptualize deep time, this does not mean that his world is supposed to be our own. Admirers of the author know that the events described in Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit span only a fraction of Middle-Earth’s known history. Middle-Earth itself, as explained in Tolkien’s The Silmarillion, is but one small part of a planet called Arda, created and ruled by a collection of gods that most certainly weren’t around when ancient humans interacted with Neanderthals.

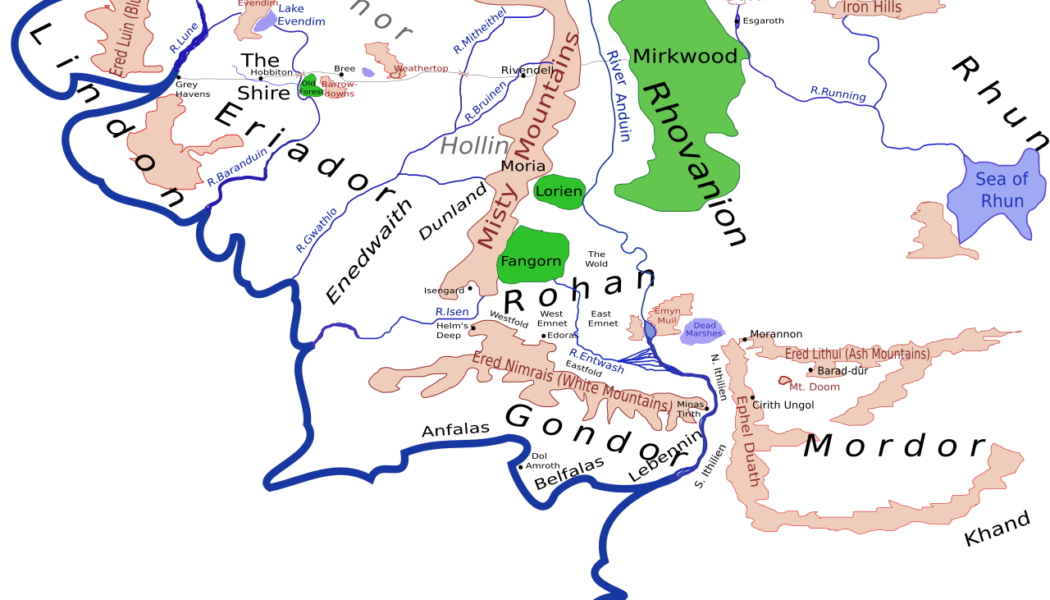

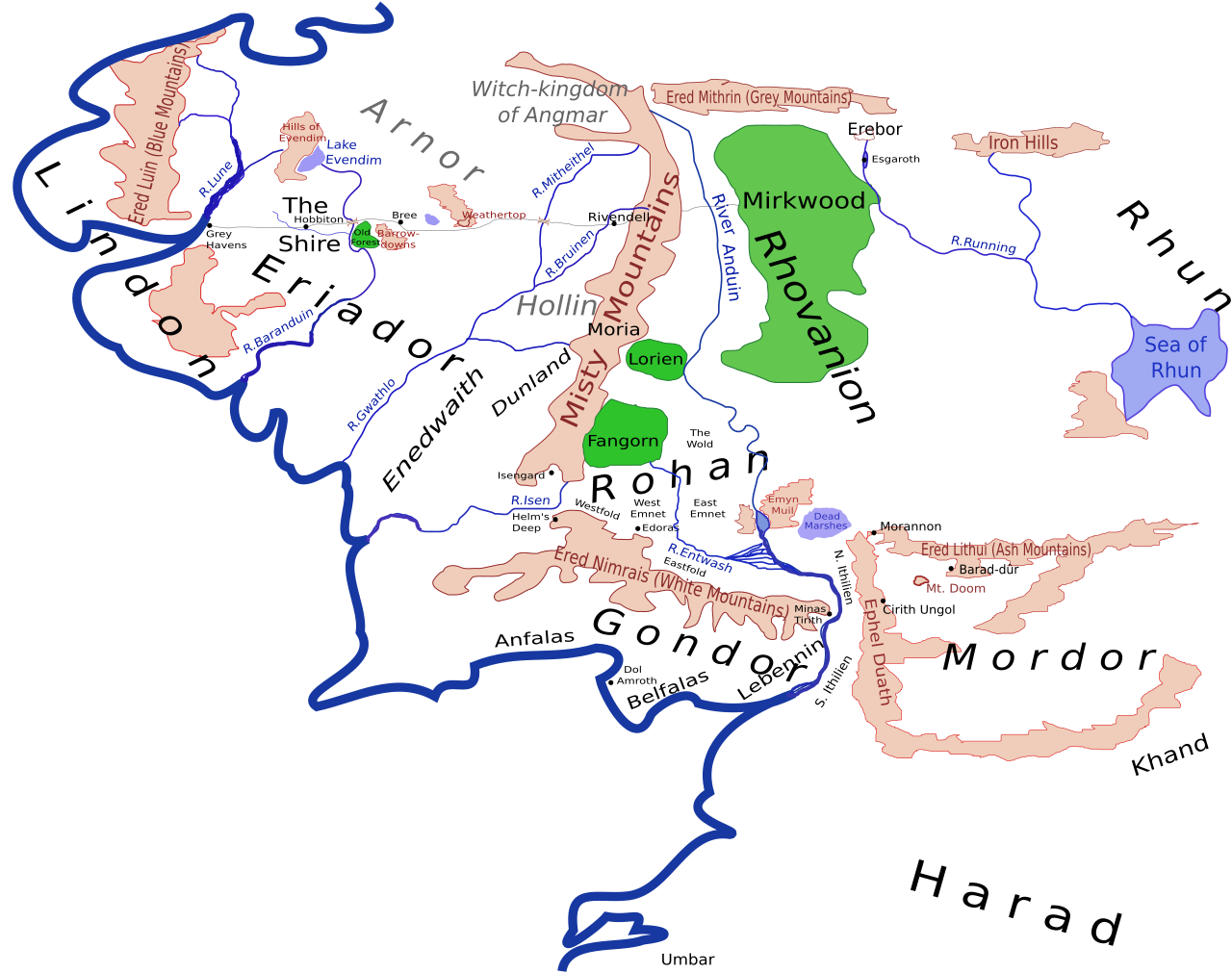

Although Middle-Earth is most definitely a fictional place, this does not mean it is completely unrelated to reality. As Tolkien stated in his foreword to Lord of the Rings, “An author cannot of course remain wholly unaffected by his experience.” Upon closer inspection, the theory that Arda is a representation of prehistoric Earth falls apart. But another interpretation of Tolkien’s magnum opus holds up under scrutiny. This interpretation argues that the various regions of Middle-Earth visited in The Lord of the Rings were inspired by, and intended to represent, specific moments in English history.

The Shire and the Anglo-Saxon migration

Despite his stature and success, Tolkien has largely been ignored by literary critics. This is probably because he wrote fantasy, a genre which to this day is often dismissed as entertainment rather than Literature with a capital L. This is arguably unfair in Tolkien’s case, as he not only taught English at Oxford University but also incorporated numerous aspects of the English language and English history into his fiction.

Nowhere in Middle-Earth are English influences as obvious as in the Shire, home of the hobbits. The word “shire,” originating from Old English, continues to be used today to denote administrative divisions in Great Britain, such as Oxfordshire. The Shire’s lush, green landscape evokes the most beautiful stretches of English countryside, while the hobbits themselves — the Banks, Boffins, Bolgers, Bracegirldes, and Brandybucks — have quintessentially English first and last names.

The history of the Shire mirrors the German settlement of Britain. The three hobbit clans that are said to have come to the Shire from the East after crossing the Brandywine River — the Stoors, Harfoots, and Fallohides — correspond to the Germanic tribes who traversed the English Channel from northern Germany and Denmark during the 5th century AD: the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. In Tolkien’s world as well as ours, the individuals who led these migrations were brothers named after horses. In Middle-Earth, they were hobbits named Marcho and Blanco, after the Celtic word marka and its Old English counterpart, blanca. On Earth, they were Hengist and Horsa, the former of which became the first Jutish King of Kent.

But the comparison goes even further. Just as England was already occupied by the Celts before the arrival of the Germanic tribes, so too does Tolkien hint that the Shire — a land everyone associated with hobbits — was once populated by another people. “The land,” he wrote, “was rich and kindly, and though it had long been deserted…it had before been well tilled: and there the king had once had many farms, cornlands, vineyards, and woods.”

The Kingdom of Rohan as England’s heroic age

In The Two Towers, fellowship members Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli pass through the Kingdom of Rohan, which they help defend from the forces of Saruman. If the Shire is meant to represent Britain shortly after the migration of the Anglo-Saxons, Rohan — a land of horses and horsemen — represents a period in English history when the Germanic peoples have coalesced into a single culture and their tribal organizations have been replaced by a more extensive and unified political order.

In Rohan, the names of people and places are pulled exclusively from Old English, the language spoken by Anglo-Saxons until the 11th century. The name Théoden, given to the King of Rohan, means just that: king. Éored, a company of riders, translates to “troop of calvary,” while Meduseld, Rohan’s throne room, means “mead-hall.”

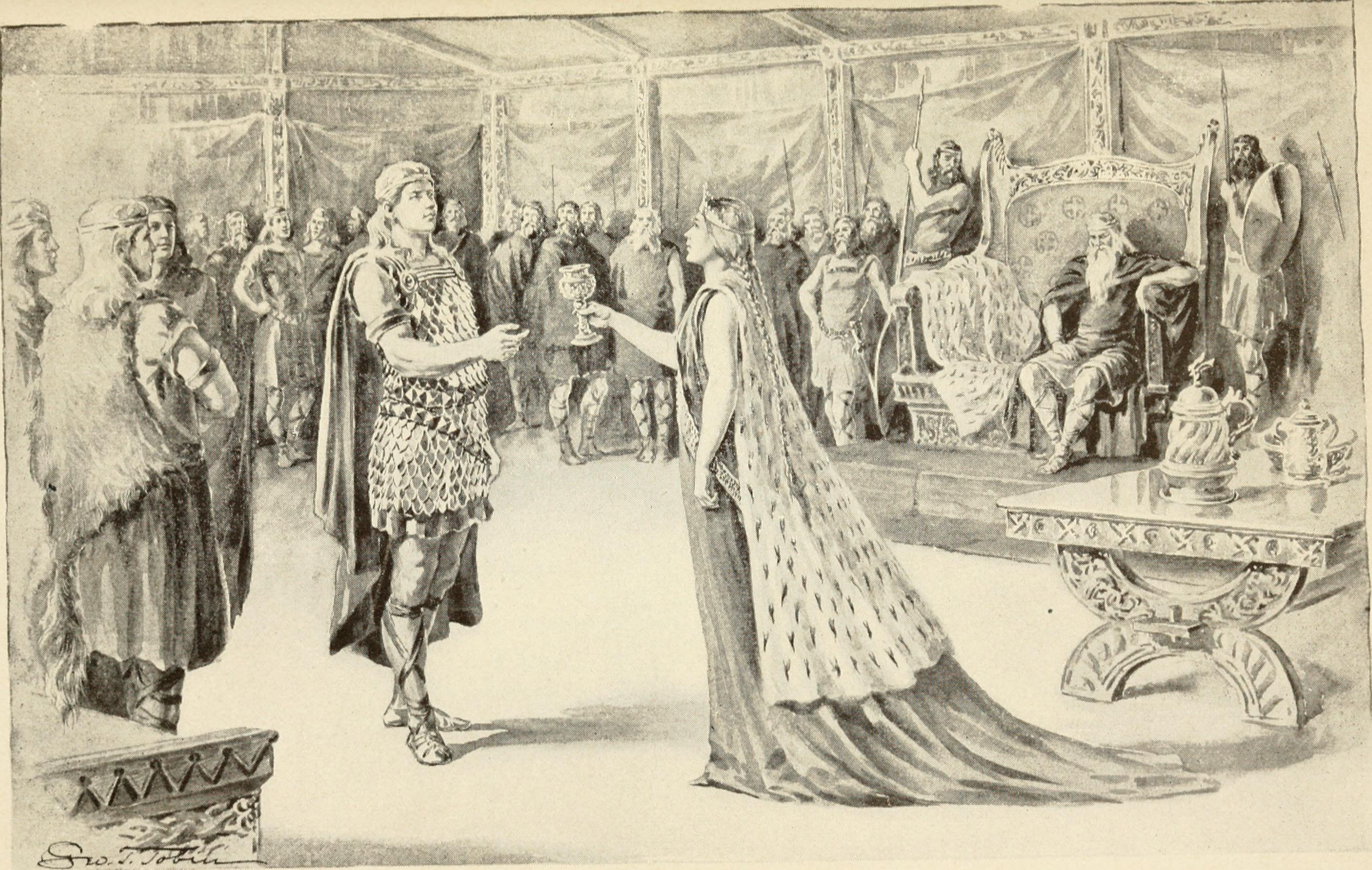

As Olivia Mathers of Elizabethtown College says in an article, “Anglo-Saxon values expressed in war poetry appear in The Lord of the Rings through the language and behavior of the Rohirrim.” The culture of Rohan, like that of the Anglo-Saxons, revolves around family, loyalty, and bravery. In life, they fight for honor and glory. In death, their bodies are interred rather than cremated, their graves covered with flowers. Aragorn’s description of the Rohirrim, as “proud and willful, but… true-hearted, generous in thought and deed; bold but not cruel; wise but unlearned,” matches the popular conception of the Anglo-Saxons.

The Two Towers pays homage to Beowulf, an Old English poem that Tolkien — in contrast to many other scholars — believed to have been composed close to the Christianization of England near 700 AD. The scene in which Aragorn, Legolas, Gimli, and Gandalf enter Meduseld to free King Théoden from the corrupting influence of Gríma Wormtongue, a servant of Saruman, greatly resembles the scene in which Beowulf has to pass by guards to enter Heorot, home of the Danish King Hrothgar. Wormtongue has been compared to Unferth, Hrothgar’s unsympathetic servant who is eventually humiliated by Beowulf.

Mordor and Isengard: post-industrialized England?

While the cultural connotations of Rohan and the Shire might be lost on readers unfamiliar with English history, the real-world implications of Isengard and Mordor, the headquarters of Saruman and Sauron, are all but impossible to miss. Mordor, a wasteland covered in fire, ash, and war machines, contrasts sharply with the natural beauty found throughout Middle-Earth. Isengard, once part of this beauty, is quickly transformed into a second Mordor by Saruman’s call for industrialization. “They come with fire,” Treebeard, an ent and living tree, tells hobbits Merry and Pippin about the wizard’s orcs, “they come with axes. Gnawing, biting, breaking, hacking, burning! Destroyers and usurpers, curse them!”

The transformation of Isengard can and has been read as a metaphor for the modernization of the idyllic England where Tolkien grew up. “Where he was raised,” Carol Thompson, curator of a “Making of Mordor” exhibition at the Wolverhampton Art Gallery, told The Guardian, “was very rural which he adored. During his later life, he said that time was his happiest. But he saw the industrial landscape encroaching on his way of life as a child. He was very open about his loathing of industrialisation.”

Tolkien juxtaposes the orcs of Mordor and Isengard, who exploit nature for their enterprises, with characters like men, elves, and especially hobbits, who respect and coexist harmoniously with their environment. The Shire returns throughout Lord of the Rings as an ideal world that’s on the brink of extinction and needs to be protected at all costs. “Concerning Hobbits,” a deleted scene in the extended edition of Peter Jackson’s film trilogy, encapsulates the universal yet, in Tolkien’s eyes, quintessentially English values that create and maintain such an ideal world.

It isn’t so much a hobbit’s passion for food, drink, or pipeweed that makes them worthy of the writer’s admiration, but their lack of personal ambition, their opposition to change, and their insistence on living a simple life of peace and quiet. It’s these same qualities that make hobbits and only hobbits capable of carrying the One Ring without succumbing to its temptations. Whereas Gandalf, Boromir, and Galadriel would be compelled to use the power of the ring to change the world in their image, Frodo has no aspirations other than to return home and continue living the way he’s always done. If the English returned to their hobbit ways, Tolkien suggests, modern-day England would look more like the Shire and less like Mordor.