“Jesus said to them, ‘Therefore every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven is like a householder who brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old’” (Matthew 13:52).

“Salvation comes, not from the destruction of tradition (progressivism) or the archaeological neutralization of tradition (traditionalism), but only when the Church, the bearer of tradition, penetrates to its true center, to the life at the heart of tradition, to that community with God, the father of Jesus Christ, that is revealed only through faith and prayer. Only when this occurs can there be that true progress that leads to the goal of history; to the God-man who is humanity’s humanization” (Pope Benedict XVI).

During the last many decades, Catholic life has been dominated by the question of tradition: what it is, whether and how it is important, and how it should take its place in the life of faith. This has not just been an occupation of academic theologians; questions concerning Catholic tradition have increasingly been taken up in popular books and talk shows, on the internet and in podcasts, and these conversations involve strongly held arguments and opinions that touch our politics, our parishes, our schools, and our own attempts to live a faithful and coherent Christian life. This essay is meant as a brief aid toward gaining a Catholic mind on this important and vexed question of Catholic tradition.

1. Tradition in Christian understanding

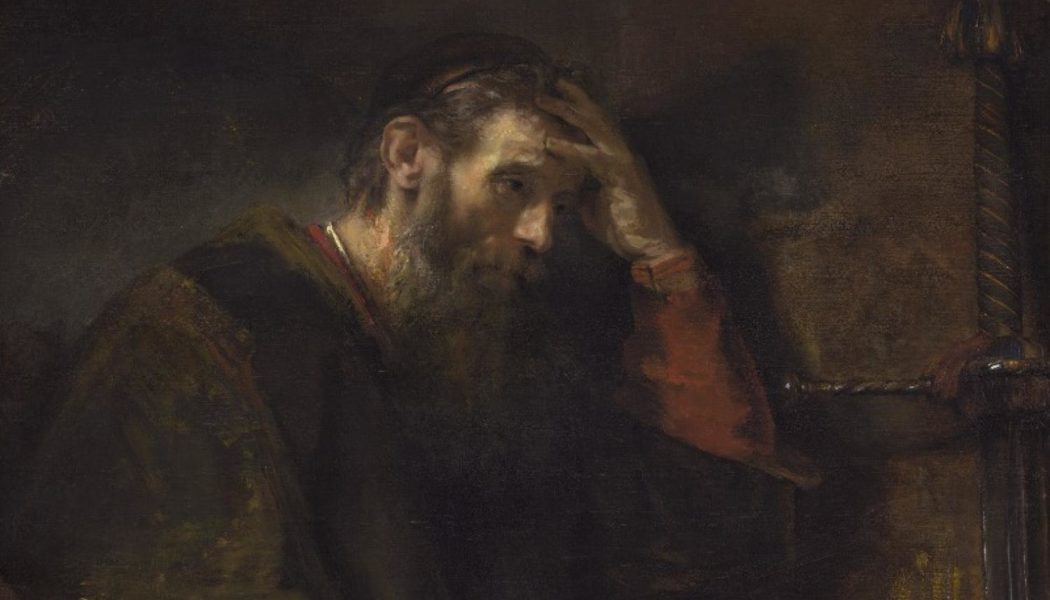

A reference to Christian tradition comes up in one of the earliest books of the New Testament. During his second missionary journey, St. Paul visited the Macedonian city of Thessalonica. His preaching had a significant effect and persuaded many Jews and Gentiles to embrace the new faith. Paul’s time in the city was brief. His success stirred up violent opposition, and after only a few weeks he and Silas had to slip away by night. Paul then wrote two letters to the Thessalonians to encourage them in their newfound faith. The second of those letters included this exhortation: “So then, brethren, stand firm and hold to the traditions which you were taught by us, either by word of mouth or by letter” (2 Thessalonians 2:15). A few years later Paul wrote something similar to another recently established Church in Corinth: “I commend you because you remember me in everything and maintain the traditions even as I have delivered them to you” (1 Corinthians 11:2). We usually connect the idea of tradition with great age: we call something traditional because it has been around for a long time. Yet here Paul is speaking of traditions that originated in the mission of Christ just a few decades previously and that were handed on to newly converted Christians only a few months before.

The etymology of the word “tradition” gives a clue to St. Paul’s meaning. Tradition comes from the Latin word tradere (in the original Greek the word is paradosis) meaning “to hand on, to deliver, or to entrust.” Paul had been entrusted by Christ with the message of the Gospel. His task as a missionary was to “hand on” that message, to entrust it to others. Tradition was thus for St. Paul a shorthand way of referring to the Gospel and all its demands. Another pair of passages in Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians underlines this meaning. He writes: “For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, ‘This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me’” (1 Corinthians 11:23-24). He writes further on: “For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received, that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures” (1 Corinthians 15:3-4). In both of these passages dealing with essential Christian beliefs, Paul speaks of first receiving and then delivering the truth in question. The word translated as “delivered” is the verb form of the Greek word paradosis, or “tradition.”

This brief foray into scriptural terminology makes clear that the essence of tradition, as the word is used by St. Paul, is intrinsically tied to the notion of truth. Tradition for Paul meant the truth of the Gospel as first taught by Christ, handed on to the Apostles, and delivered to others as the foundation of the Church and the basis of the Christian faith. In this sense, tradition refers to what has been revealed by God as perennially true, what Paul elsewhere called the deposit of faith. It has now been two thousand years since the Gospel was first preached and handed on by the Apostles, so the Christian tradition now has the flavor of something long-standing. But Christians value the traditions of the Gospel not mainly because they have been around for a long time, but because they have been revealed by God and are always true and ever fresh. They were as “traditional” in the first century as they are in the twenty-first.

2. Tradition and traditions

The word “tradition” has other related meanings that go beyond the scriptural use of the term. Many things of different kinds have been “handed on” to us by previous generations. Some are evidently more important than others. How are we to evaluate their relative significance? We might note three broad categories of tradition that have been recognized by Christians over the centuries: (1) the traditions that were handed on from the Apostles, usually called simply “Tradition with a capital T” or the “Apostolic Tradition”; (2) various expressions of Christian faith and life that have arisen and have been handed on by Christians in different times and places and are often called “Ecclesial traditions”; and (3) cultural practices of all kinds that are passed on from generation to generation.

The Catholic Catechism explains the difference between the first two types of tradition just noted, supplying a distinction that is itself part of Catholic tradition:

The Tradition here in question [sacred Tradition] comes from the apostles and hands on what they received from Jesus’ teaching and example and what they learned from the Holy Spirit… Tradition is to be distinguished from the various theological, disciplinary, liturgical, or devotional traditions, born in the local churches over time. These are the particular forms, adapted to different places and times, in which the great Tradition is expressed. In the light of Tradition, these traditions can be retained, modified or even abandoned under the guidance of the Church’s magisterium (CCC 83).

The two types of Christian tradition referred to in the Catechism are closely related. Particular traditions are not entirely separate from the Apostolic Tradition; they are expressions of it, specific incarnations of the truths of the faith. Christian faith and doctrine are not just abstract ideas; they gather up all the elements of life and thought and clothe themselves in the languages and customs of local cultures. Such particular ecclesial traditions are not only of great value, they are necessary if Christ’s truth is to come fully alive. Yet they need to be held up steadily to the light of the Apostolic Tradition such that they maintain their purity and their usefulness. The truth, though unchanging in itself, needs constant re-articulation and re-translation among the different and often rapidly changing human societies within which it takes root. Words and customs often change their meaning over time. Under the Holy Spirit’s guidance, the Church “retains, modifies, or even abandons” such local traditions such that the Tradition can be presented and handed on anew in all its force and purity to every generation.

A third kind of tradition can be noted: namely the whole pattern of living and thinking that every society hands on to its younger members. Customs of language, education, governance and social ordering, economic practices, an entire way of life down to detailed matters of food and dress, all fall under this category. Some traditions of this kind are of great value, expressing and incarnating important human truths and reflecting something of God’s original intentions in humanity’s creation. Many are of a morally neutral character, like a particular language or a local cuisine. Some are unhealthy or morally evil, the result of fallen humanity’s habitual corruption.

The Church deals with these three kinds of tradition differently. As to the first, the Apostolic Tradition, the substance of divine revelation itself, the Church carefully protects and proclaims it and lets nothing obscure or replace it. Regarding the second, specific ecclesial traditions, the Church honors them and values them, guiding, nurturing, and adjusting their practice so that they can continue to be effective means of incarnating the truths of the Deposit of Faith. In dealing with the third type, human traditions of all kinds, the Church sifts and sorts them, supporting and encouraging what is valuable and working to mitigate or eliminate what is harmful or evil. The careful handling of these different kinds of traditions has given the Church a remarkable quality of being both changeless and culturally adaptive. Founded on the perennial truths revealed by Christ, the Church is an immovable rock amid a world of constant change. Attentive to the task of clothing the truth in the changing languages and cultures of humanity, the Church puts down roots in human soils of all kinds, affirming and transforming those cultures in the process. As a result, the Church has been a potent agent of both change and continuity in the various cultures it has encountered and inhabited.

3. Christianity and Tradition

Respect for traditions of all kinds has been a universal human practice. Virtually all human cultures have honored the traditions they have received from their forbears and have attempted to live within the contours of what was handed down to them. It has been a general cultural rule that what was new was suspect and needed to prove itself, while what was time-tested was respected and followed. To some degree this has been a matter of simple survival in an often-hostile physical and social environment. If every generation needed to learn for itself the difficult skills required for staying alive and maintaining social order there would be little chance of continuing in existence. Living by inherited traditional wisdom has made good practical sense.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity