Hey everybody,

Today is the Feast of St. Thomas Aquinas, and you’re reading The Tuesday Pillar Post.

If you’re reading The Pillar, you already know a little bit about the Angelic Doctor, and the substantial contributions he made to Catholic theology and Western philosophy.

You probably also know that for Thomas, theological and philosophical work was part of Christian discipleship — that he wanted to be close to the Lord Jesus Christ more than he wanted to win renown or accolades as an intellectual. You know that Thomas — who cried often in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament — was a saint.

And you’ve probably also heard, more times than you can count, that Thomas Aquinas was fat.

But that’s one thing we really don’t know at all.

It is a great piece of Catholic lore that Aquinas was a corpulent man. It’s often said that his desk had a cutaway to accommodate his gigantic girth. I read recently a paper claiming that St. Thomas was a compulsive over-eater and morbidly obese.

Some of this seems to have started with Chesterton, who called him a “walking wine-barrel.” Some of it is legend.

But today I’m going to burst your bubble. We really have no idea about Thomas’ waistline.

The earliest accounts, especially from his biographer William of Tocco, describe him as tall and physically imposing, and also quite strong. His head was especially described as being quite large (a virtual planetoid, perhaps). There is no mention of any portliness whatsoever.

There’s nothing morally flawed in being girthy, and there’s no reason to regard that as an impediment to holiness. In fact, the more we learn about physiology, the more we realize that the connection made often between moral virtue and physical condition is tenuous for many people, whose health might be impacted often by unseen or even unknown factors. Bearing such a cross well might itself be a means to holiness.

But I find this most interesting as a point about the flow of information. Sometimes something “everybody knows” is really something that nobody knows at all. That’s the kind of thing St. Thomas aimed to correct, actually.

Still, he’d probably be fine if you had a piece of pie in his honor.

Alright, we’ve got a lot of news, let’s get to it.

The news

The cardinal claims that in February 2020, Pope Francis lifted some of the restrictions, permitting him to resume pastoral ministry.

But the Vatican says otherwise —that there are (unspecified) disciplinary measures against the cardinal, which remain in force, and that only occasional and specific permissions have been given for the cardinal to engage in ministry.

All of that is surprising, given the fairly public ministry profile Cipriani has had in recent years, raising questions about whether he observed or ignored the Vatican’s restrictions, or whether he took a small particular permission given by Pope Francis, and expanded it more broadly into the “extensive pastoral activity” he says he has undertaken in recent years.

But here’s the bottom line of this news. In 2018, a cardinal was accused of sexual abuse. He had no trial. His resignation was quietly accepted, and then he was placed under secret restrictions. He seems not to have obeyed those secret restrictions, and there seem to have been no consequences. He claims they were secretly lifted.

That sequence does not reflect due process or transparency. And we’re not talking about something from 20 years ago. We’re talking about a post-McCarrick sequence of events.

I think this story would be a relatively big one, if it weren’t an account of exactly what most people have come to expect.

With the third-largest Catholic population in the world, the Filipino Church does not yet include deacons not seeking eventual priestly ordination. But as the bishops meet in plenary assembly, that looks like it’s about to change.

Here’s a report, from our Filipino correspondent on the ground, near Manila.

That was, as you can imagine, a very intriguing kind of catnip for a lot of people online — with many declaiming that Biden must now be excommunicated.

As it happens, The Pillar’s Ed Condon is an expert on the canon law surrounding Freemasonry. And in a very good analysis, he broke down the interesting and complicated case of Biden’s Masonic association — including an excellent history of why Catholics don’t like masons to begin with.

Really, this is great analysis. Read it here.

And sources have told The Pillar that at least one other abuse allegation against the order’s founder was reported in the Church, but not investigated.

The Institute of the Incarnate Word is an Argentine religious community recently taken over by the Vatican, over concerns about its governance, formation, and ongoing reverence for its abusive founder. The institute has a marked presence in the United States, including a residential high school seminary.

Until now, there has been little reporting on the extent of seemingly unresolved abuses within the order. The Pillar aims to change that.

The charging documents indicate that the priest is accused of placing a minor’s hair in his mouth, presumably without consent. The priest’s attorney says he did not do that, and only touched the girl’s hair while he was making jokes about its suitability for dental flossing.

Martins pleaded not guilty to the battery charge on Monday.

Become a True Leader with an MBA from the University of Mary. Gain the confidence of an executive, the insight of a specialist, and the integrity to be a champion for the Common Good. Pillar paid subscribers receive an exclusive $10,000 scholarship – Apply today!

While alleging that those resettled refugees are “illegal immigrants,” Vance suggested that the USCCB’s interventions on immigration are rooted in concerns about “the bottom line.”

We got curious about how the large refugee contracts actually impact the USCCB’s bottom line, so Brendan Hodge broke down the numbers — and from a purely profit-and-loss standpoint, it turns out that the USCCB would be better off without the refugee contracts at all.

The reaction to that analysis, and to this entire debate, has been divided.

I have been especially interested in Catholics who argue, in good faith to be sure, that bishops themselves take a more liberal approach toward migration and refugee issues because of their desire for institutional self-protection, and —therefore — desire to keep money flowing toward institutions like Catholic Charities.

I think those arguments are made in good faith — and I’ve written a lot at The Pillar about the episcopal instinct for institutional preservation, even against the good of the institution’s mission or the mission/witness of the Church.

But to me, that doesn’t seem reflective of the bishop’s approach to immigration.

Candidly, I don’t think very many U.S. bishops feel the same kind of responsibility for refugee programs at their local Catholic Charities as they do for their seminaries, chanceries, and other more ecclesial institutions. In fact, if federal grants were to go away, I think there are at least a few bishops who would fit a Catholic/religious persecution narrative into their self-understanding, and then move along without much further reflection.

In short — for better or worse — I don’t think very many bishops actually think that refugee resettlement dollars are such a vital part of the Church’s life that they have to make statements just to keep them coming in.

And if losing grants meant that certain Catholic Charities centers were shuttered, and jobs were lost, and other related programs foundered, I think there are a cadre of bishops who would solemnly declare (and believe) that those things were lost because the bishops dared speak the truth. And then they might not think about it very much more at all.

(By the way, many of those grants may go away in the next few years simply because of the president’s intention to dramatically slash the federal budget. When they do, I think a lot of Catholic Charities programs will be cut fairly quickly, as bishops don’t have other pools of money waiting for them).

In the Church, narrative is often a more valued currency than coin, and seeing government grants cut off in the face of episcopal opposition makes for a powerful narrative.

So if I’m right, and it’s not about money, why do bishops advocate so strenuously on immigration? And why do conference statements get so much more specific on policy than a basic and complete recital of Catholic social teaching on the subject?

I think all bishops believe there is a moral obligation for the Church to provide immediate material and spiritual assistance to people in America, regardless of their immigration status, as a mandate of the Gospel, and I think they want to preserve that right.

I think there are some principles that bishops generally take as inviolable, like the sovereignty of the family, and the right to worship, and I think most want to find ways to emphasize those principles.

I think bishops are especially concerned to see that people who have become their parishioners are treated with dignity and justice, and are able to continue the practice of the faith.

But on more specific details of immigration enforcement and policy, I think there are some bishops and staffers who take strongly a particular vision on the subject — a vision that takes a fairly absolutist view on some questions of prudential judgment.

And then I think there is a great swath of bishops with an emotional and pastoral desire to do something to aid their parishioners, who have accepted the bishops’ conference as basically expert on the subject, and who take staffer suggestions as basically fait accompli.

That combination allows one approach to immigration questions to be equated at the conference with “The Catholic Position” without much debate or even discussion beyond the relevant episcopal committees.

The discussions which do come up in floor sessions are mostly peppered with bromides or pastoral anecdotes. I suspect that the bishops who might ask hard questions are mostly afraid that doing so would label them anti-immigrant, and anti-Francis.

Of course, few bishops have policy expertise, and can hardly be faulted for being uncertain as to how to assess the details. But there is a good question to be asked about the extent to which the conference should be doing that in the first place, especially when issues go from the realm of moral absolutes to the realm of prudential judgment. And there are fair questions to be asked about what points the bishops choose to emphasize in their advocacy and public statements on immigration.

And it’s also understandable that when the conference is responsible for $100 million in immigration-related deliverables, that there will be questions about which of its statements are Catholic social teaching, and which are matters of prudential judgment — even if Vance’s approach to that doesn’t seem an accurate read of the situation to me.

I think those questions should be asked, fairly and directly, and I think it’s reasonable to expect conference staffers and relevant committee members to provide insight into how the USCCB approaches controversial questions dividing Catholics.

But to date, my interview requests on the subject have not yet been granted.

But you can read about government grants and the USCCB, right here.

And we’ll aim to have more coverage of this subject in the days to come.

—

Georgia on my mind

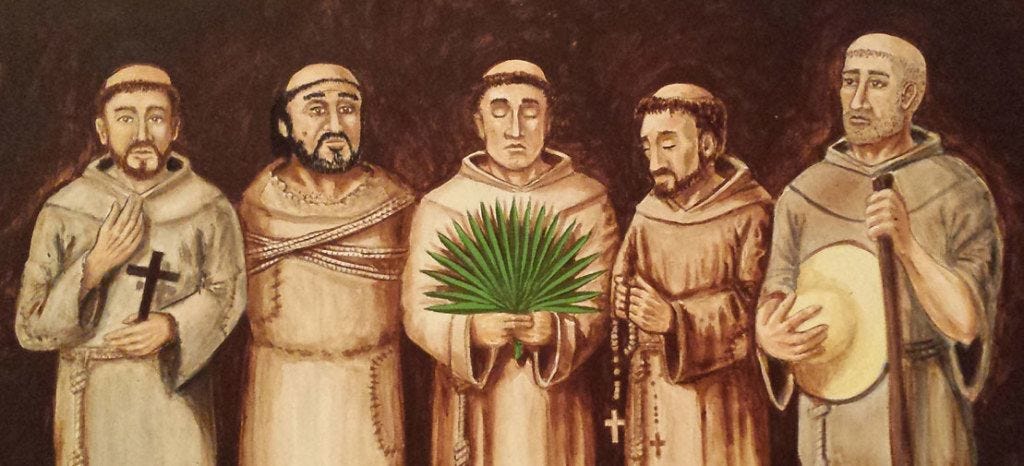

Pope Francis yesterday cleared the way for the beatification of five Spanish Franciscans who were killed in September 1597, as they ministered to the Guale people in what is now Georgia.

Coming from St. Augustine, Franciscan friars travelled in the last 1500s up the Georgia coast, to preach the Gospel among the Guale people. They did so effectively enough to make a lot of converts. Friars lived among the Guale with no military protection, baptizing babies, witnessing marriages, and translating Scripture, as I understand it.

But in 1597, a man named Juanillo, the son of a Guale chief, wanted to take a second wife, as was his tribe’s custom. Fr. Pedro de Corpa told Juanillo that there could be no wedding for his (second) intended.

Juanillo exploded. He killed Father de Corpa immediately.

Then in indignation, he gathered a group of young men, with a mission to kill other friars.

One local chief tried to warn two friars that Juanillo was coming. But the priests refused to flee. Instead, they hid inside their church.

Juanillo found and killed them there, as they were at prayer.

The men found two other friars near their missions, and killed them too.

One more friar, Francisco de Avila, was kidnapped and tortured, not released for months.

The five martyred men were Friar Pedro de Corpa, Friar Blas Rodríguez, Friar Miguel de Añon, Friar Antonio de Badajóz, and Friar Francisco de Veráscola.

There is not yet a date for their beatification. But they are no doubt interceding now for the Church in the United States. May they intercede for each one of us.

Please be assured of our prayers. And please pray for us. We need it.

If you can, please subscribe to The Pillar, so we can keep it going, and growing:

And for President Biden, here’s a classic:

Yours in Christ,

JD Flynn

editor-in-chief

The Pillar

Become a True Leader with an MBA from the University of Mary. Gain the confidence of an executive, the insight of a specialist, and the integrity to be a champion for the Common Good. Pillar paid subscribers receive an exclusive $10,000 scholarship – Apply today!

Comments 45

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews