Early on Easter Sunday morning, April 3, 1994, a priest rushed to a Paris hospital.

He was carrying the Blessed Sacrament.

When he arrived, it was too late. The man due to receive Viaticum was already dead. The agony that had started on Good Friday, shortly after receiving the Last Rites, and that, by Holy Saturday, had worsened with breathing difficulties, now was ended.

Alone, that morning at approximately 4 a.m., Jérôme Lejeune had passed from this life to the next.

Born in 1926, by the early 1950s, Lejeune had become a doctor. Thereafter, he was handpicked to carry out research into a medical condition known as Down syndrome. In 1958, the young researcher made a discovery that at last explained the origin of this. He found that children so afflicted had an extra chromosome. Soon after, his findings were published, and with that his professional reputation was sealed.

The years that followed immediately after were of plaudits and praise, awards and growing prestige, as Lejeune became a regular attendee at international conferences, a much sought-after speaker, an expert witness to parliaments and governments. In 1962, he came to the United States to receive, from the hands of the then-president, the Kennedy Prize. At that time, there was even talk of the Nobel Prize. The professional path ahead looked a wide and a smooth one for Professor Lejeune.

In addition, there was the possibility of his becoming a wealthy man with a thriving private practice. Deliberately, he chose a more modest lifestyle. Another consultant once remarked to Lejeune’s daughter that while he came to the hospital in a Ferrari, her father arrived on a bicycle. The healing of the sick was not a career for the Frenchman — it was a vocation.

And so, just another doctor, Lejeune was constantly on call, available at all hours to his patients and their parents — many of whom, initially at least, struggled to cope with a Down syndrome child. Here, he understood not just the medical issues at stake, but the very human ones. Even in the evening and on weekends, his home phone would ring with still more calls upon his time; the phone calls were taken without fail, as distressed voices on the other end of the receiver were met by a consoling one.

The public figure that he became was distinct from the very private man he remained. Lejeune had met his wife — a Danish Protestant who later converted to Catholicism — at university. The occasion for their first meeting was the college library. She was looking for a pen, and he offered his. Later both agreed it was love at first sight. Until the end of his life, and despite all the ups and downs of the years that followed, when on his many trips abroad, it was with that same fountain pen that Lejeune was to write to his wife.

Family was important to him. Lejeune passed up the numerous opportunities for business lunches, preferring instead to eat each day with his wife and their ever-growing family. (They were to have five children.) There was a daily rhythm to the Lejeune household — one that concluded with family prayer each evening, when entreaty would be made for many, but especially for the sick.

Although a man totally committed to his work, he knew the value of rest. On Sundays the family would attend Holy Mass at the local parish church, where Lejeune sang in the choir. When he could, on Sunday afternoons, he would head out into the countryside for long walks, often with nothing for company other than a walking stick and a small wooden rosary he had carved. There, he would walk and pray while rejoicing in the natural world he observed all around. Sometimes, however, he would simply sit, and with a piece of wood carve yet another rosary. He enjoyed giving these as presents to friends and family, but there was always a charge — the owner had to “say a decade” for the carver.

By the early 1970s, pressure was growing for a change in France’s abortion laws. Around that time the parents of a young Down syndrome patient took him to see Lejeune. When they arrived for the consultation, the 10-year-old boy was weeping uncontrollably. His parents explained to Lejeune that the boy had been upset since watching a television debate during which there had been calls for children with Down syndrome to be aborted. Suddenly, the boy threw his arms around the neck of the professor, crying out as he did so that Lejeune had to defend children like him as they were just too weak and couldn’t defend themselves.

Lejeune’s embrace of that cause of life soon moved him from national hero to pariah, vilified in the press and elsewhere. By the early 1970s, his children cycled to school past walls daubed with the threat: “KILL LEJEUNE.”

Lejeune had seen this coming. Once, while at debate at the United Nations, he heard a call for the death of the unborn in the womb when there had been some abnormality diagnosed. As the discussion was drawing to a close Lejeune took to the podium. His contribution took an altogether different view than what had preceded him. He talked not of disability, but of the dignity of each human life, of the “little man” that existed in the womb, defenseless but still fully human. That day, however, he was a lone voice. That night, he wrote to his wife that any talk of a Nobel Prize was now redundant.

Professor Lejeune could not be silenced, so he had to be marginalized. The dead hand of bureaucracy was applied to his work as research funds were slowly choked off. Years passed without any salary increase as he was sidelined academically, and eventually, in 1982, his laboratory was closed down. Thereafter, what little research he did was with funds from aboard. Lucrative career offers came from America, but he declined them, preferring to stay in his homeland and serve as best as he could.

Lejeune once described the life of a researcher as that of one who goes round and round until he finds an open door. In 1994, a door opened when Pope John Paul II made him president of the new Pontifical Academy for Life. His friendship with the pontiff was by then already long standing. Whenever Lejeune was in Rome, both he and his wife would attend the early morning papal Mass, followed by breakfast with the Pope. Both men had much in common: both were fighting a voracious Culture of Death, a war not against people but against false ideas. Lejeune’s arguments for the protection of the unborn may have been based upon scientific fact — there really was a child present in the womb — but the strength he got to continue arguing that came from his faith.

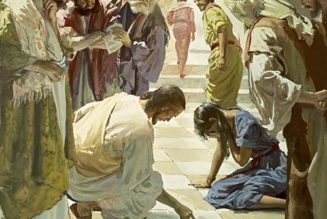

After his death, among Lejeune’s personal effects was discovered a letter, one that had never been sent. Writing to his brother, uncharacteristically, Lejeune revealed something of the depth of his faith, and specifically of an experience while on a recent trip to the Holy Land. He recounted how, at Tiberias, “in this little chapel … on [a] flagstone … I stretched out full length to kiss the imaginary footprints of Him who was present there… I was spiritually transported… When I got up, I laughed … with all my scientific knowledge, I had only been able to offer … an ancestral prostration…. And I set off again towards the Sea of Galilee, carrying with me the certainty that Jesus has prepared encounters and a marvelous intimacy for mankind … which is only discovered … when we see it from the other side.”

That “other side” opened to him soon after when, just 33 days after his appointment as president of the Pontifical Academy for Life, Professor Lejeune died of cancer at a Paris hospital. On hearing of the death of the man who had become his close friend, Pope John Paul wrote:

We are faced today with the death of a great Christian of the 20th century, of a man for whom the defense of life became an apostolate. It is clear that, in this present world situation, this form of lay apostolate is particularly necessary. … [He] has left the truly brilliant witness of his life as a man and as a Christian.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity