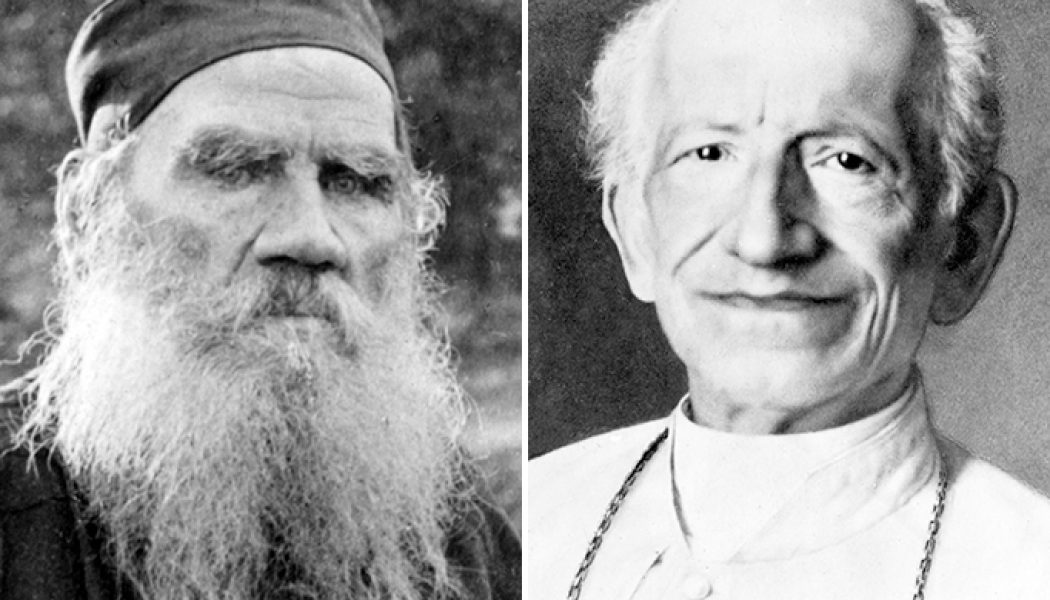

When Lions Clash: Leo XIII vs. Leo Tolstoy

Tolstoy taught a progressive sense of “liberation” from marriage. Leo XIII understood the illusory nature of this freedom.

In 1893, Pope Leo XIII established the Feast of the Holy Family. At the time, the family faced threats from the state and progressive movements like socialism. This year, we mark the 140th anniversary of Leo XIII’s encyclical Arcanum Divinae (“Divine Mysteries”). The encyclical Arcanum sought to uphold the Christian family in light of the “progressive” threats of civil marriage, polygamy and divorce.

Pope Leo XIII faced a formidable literary opponent at the time — Leo Tolstoy, whose works War and Peace (1869) and Anna Karenina (1877) were celebrated as masterpieces. Tolstoy virtue-signaled “traditional family values,” presenting himself as an ascetic Russian Orthodox patriarch with a large family. Anna Karenina seemingly condemned adultery and divorce, while his controversial Kreutzer Sonata (1889) inveighed against contraception and pornography.

Many conservatives embrace both classics as affirmations of marriage and family. Tolstoy’s apparent wholesomeness has made him perennially popular. The HBO/BBC War and Peace (2016) starring Lily James, Paul Dano and James Norton ends with Pierre and Natasha happily married with a large family.

On their glittering and masterful surface, Tolstoy’s works validate family, Christianity and civilization, beginning with his early novella Family Happiness (1859). But Tolstoy was a revolutionary who looked to overthrow all three. He stood between the French and Russian Revolutions, bridging them with eccentric utopianism and advocating modern sexual mores.

Pope Leo XIII understood this, though he was not a novelist, and it is unknown if he read Tolstoy. In Arcanum, Leo XIII discussed how communists and Mormons, like the Gnostics and Manicheans of old, sought the destruction of Christian marriage. He said of those who sought to legalize divorce:

If they do not change their views, not only private families, but all public society, will have unceasing cause to fear lest they should be driven into that general confusion and overthrow of order which is even now the wicked aim of socialists and communists.

Leo XIII stated that the Council of Jerusalem “reprobated licentious and free love,” long before the term “free love” was coined by 19th-century “progressives.”

Tolstoy’s infamous Kreutzer Sonata appears superficially as a condemnation of contraception. The murderous husband denounces “scoundrel doctors” who prescribe contraception for his frequently pregnant wife. Yet he describes children as a burden, saying that he and his wife used them as weapons.

In Anna Karenina, Dolly considers herself morally superior to the titular character because of her constant pregnancies, yet thinks to herself:

Looking back at the whole of her life during those 15 years of wedlock, ‘pregnancy, sickness, dullness of mind, indifference to everything, and above all, disfigurement… And when I am pregnant become hideous, I know. Travail, suffering, monstrous suffering, and that final moment… then nursing, sleepless nights, and that awful pain! … What is it all for? What will come of it? I myself, without having a moment’s peace, now pregnant, now nursing, always cross and grumbling, tormenting myself and others, repulsive to my husband.

Dolly condemns Anna’s contraceptive use, yet her perspective on her pregnancies is negative. She sympathizes with a poor peasant woman who thanks God for “taking” a child, so she has enough food for the rest of her family. The peasant woman sees her dead child as a blessing. The philosophical Constantine Levin distances himself from his wife Princess Kitty when she is pregnant. It’s no surprise that Kitty assumes that Levin is having an affair with the titular character when he speaks of meeting her. Levin flees Kitty’s side during childbirth every time she cries out in pain, punishing her for not fitting his ideal. Finally, he regards his newborn son Dimitri with disgust.

Tolstoy can get more heavy-handed in putting pregnancy, the “crown of marriage,” in a negative light. The luminous Natasha loses her beauty, along with her talent for song, after bearing four children at the end of War and Peace. In The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886), the title character’s idyllic marriage ends with his wife’s pregnancy. Children are conceived of as competitors with the marital relationship. It is notable that War and Peace opens with the handsome Prince Andrei emotionally abusing his expectant wife Princess Lisa; he devalues her, then discards her for battle out of his own bloodlust.

Leo XIII, on the other hand, sees the procreative aspect of marriage as a blessing. He begins Arcanum saying:

God thus, in His most far-reaching foresight, decreed that this husband and wife should be the natural beginning of the human race, from whom it might be propagated and preserved by an unfailing fruitfulness throughout all futurity of time.

Later, he speaks of the “many and glorious fruits of marriage” with its “fertile and saving power.” He comments:

Not only, in strict truth, was marriage instituted for the propagation of the human race, but also the lives of husbands and wives might be made better and happier.

Leo XIII did not consider parenthood opposed to marriage.

When Tolstoy was penning Kreutzer Sonata, he was corresponding with Alice Bunker Stockham, who prescribed karezza, a notoriously unreliable form of contraception. Though she condemned artificial contraception and abortion, she redefined spousal “continence.” Stockham advocated abstinence during pregnancy and nursing, yet she encouraged masturbation. Tolstoy translated her Tokology: A Book for Every Woman (1886) into Russian and wrote its foreword. Stockham eventually visited him in Russia, writing Tolstoy: Man of Peace (1900).

For the late 19th century, Tolstoy considered himself “woke” for championing contraception as “women’s rights.” In Kreutzer Sonata, he deemed marriage as nothing more than legalized prostitution, using the name of Christianity. In his epilogue, he denied that Jesus sanctified marriage.

Pope Leo XIII did not see this “progressive” thinking as the path to women’s liberation. He wrote of how in ancient Roman times, “When the licentiousness of a husband showed itself, nothing could be more piteous than the wife, sunk so low as to be all but reckoned as a means for the gratification of passion, or for the production of offspring.” In Christian marriage, however, he said:

Since the husband represents Christ, and since the wife represents the Church, let there always be, both in him who commands and in her who obeys, a heaven-born love guiding in their respective duties…The dignity of the woman was asserted and assured; and it was forbidden to the man to inflict capital punishment for adultery, or lustfully and shamelessly to violate his plighted faith.

Equality and justice come from divine love, rather than from thwarting Nature.

Tolstoy would use the powerful platform of literature to call for easy divorce; Leo XIII addressed this threat directly. In Anna Karenina, Alexei Karenin’s refusal to grant his young wife a divorce shows his cold desire for power. In Kreutzer Sonata, the murderous husband longed for divorce and remarriage. Leo XIII, on the other hand, praises his predecessor Pius VII for refusing to grant Napoleon a divorce from Josephine. Leo XIII warned of the “evils that flow from divorce.” He said:

Matrimonial contracts are by it made variable; mutual kindness is weakened; deplorable inducements to unfaithfulness are supplied… the dignity of women is lessened and brought low, and women run the risk of being deserted after having ministered to the pleasures of men.

It is no wonder Leo XIII equated divorce with a “virulent contagious disease.”

Tolstoy’s “woke” hypocrisy is shown in his real condemnation of the family, which shows itself in his frequent treatment of homosexuality. “Love” finds its apex where the partners are in each other’s image. The sole harmonious couple in Anna Karenina is a pair of soldiers called “the inseparables” at St. Petersburg’s Cadet Club. They agree about wine and billiards. In War and Peace, Prince Andrei is “aroused by the sight” of the sight of bathing soldiers. When Pierre joins the Freemasons, he dreams of his benefactor Osip. Prince Andrei and Pierre bond better with each other than their wives; Pierre is enamored of Prince Andrei’s handsomeness and idealism. They mutually adore Napoleon. In Kreutzer Sonata, the murderous narrator is nonchalant about his adolescent sexual activities with other men — but his first sexual experience with a woman is depicted as his fall from grace.

Tolstoy wrote in his diary in August 1894:

Novels end with the hero and heroine married. Instead, they should begin with the marriage and end with the couple liberating themselves from it.

He was teaching a very “progressive” sense of “liberation.” Leo XIII understood the illusory nature of this “freedom.” He warned against those “who worship above all things the divinity of the State.” When he wrote Arcanum, progressivism was as much a threat to the family as it is today. His pronouncements from 140 years ago are still valid. He powerfully reminded his readers back in 1880:

Christ Our Lord raised marriage to the dignity of a sacrament; that to husband and wife, guarded and strengthened by the heavenly grace which His merits gained for them, He gave power to attain holiness in the married state; and that, in a wondrous way, making marriage an example of the mystical union between Himself and His Church, He not only perfected that love which is according to nature, but also made the naturally indivisible union of one man with one woman far more perfect through the bond of heavenly love.