Suzanne Nunn prays the rosary with friends each morning in her Mission Viejo home. From St. Timothy’s Catholic Church in Laguna Niguel, she brings Communion to the sick and homebound. She drives parishioners without transportation to Sunday Mass, decorates the altar for holidays and instructs adult converts in the tenets of the faith.

One observing the 68-year-old in her church volunteer work or at prayer in her regular pew might struggle to comprehend another role she plays in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Orange: the target of a protracted and expensive legal crusade by the bishop.

For more than three and a half years, Bishop Kevin Vann has pursued a libel lawsuit against Nunn over an email she sent to 47 people in 2020 about what she saw as his improper meddling in the finances of a Catholic foundation where she worked.

Vann, the leader of Orange County’s 1.3 million Catholics, has persisted in the litigation despite court defeats, including a stinging January ruling in which a Superior Court judge threw out his entire suit against Nunn and voiced support for her criticism of the bishop. The decision means that, unless an appellate court intervenes, the bishop will be responsible for Nunn’s legal bills, calculated at nearly $2 million by her attorneys in court filings requesting repayment.

Where that money would come from is unclear. So is the source of funding for extensive legal work on the bishop’s behalf by a Costa Mesa firm. A spokesman for the diocese declined to answer questions about the financing of the litigation, including whether it is being underwritten by Sunday collections or other donations from the faithful.

Nunn and the bishop, 73, would seem unlikely foes. They are generational peers raised in large and devout Midwestern families, he the eldest of six in Illinois, she the eldest of eight from Ohio. Both have dedicated years to building up the church in Orange.

Those who know Nunn say the suit has crushed her at a time when she is struggling to care for her husband, 81, who has dementia. As Vann vs. Nunn dragged on, she lost her career, financial security and the respect of the institutional church. But not her faith.

She has not spoken publicly about the case, and neither she nor her attorneys responded to messages seeking comment. She wrote in one court declaration that, as a matter of conscience, she could not apologize to the bishop because “each and every word” of the email in question was true.

As the court case dragged on, Suzanne Nunn lost her career, financial security and the respect of the institutional church. But not her faith.

(Krista Bruckner)

“What would Jesus do in this situation?” Nunn’s daughter, Krista Bruckner, wrote in February to the Vatican’s U.S. nuncio, or ambassador, Cardinal Christophe Pierre.

The letter received no response. Vann declined an interview request and did not provide answers to written questions from The Times. He has said in court filings that he acted conscientiously toward the foundation where Nunn worked and that her email damaged his reputation by falsely suggesting that he did not respect the wishes of its donors.

“We are confident the appeal will be meritorious,” diocesan spokesman Jarryd Gonzales said in a statement. Calling the contents of Nunn’s email “completely and demonstrably false,” he added, “We are committed to setting the record straight.”

::

Vann arrived in Orange from the Fort Worth diocese in 2012. The new assignment put him in charge of opening and paying for Christ Cathedral, the diocese’s recently acquired headquarters in Garden Grove. Built by televangelist Robert Schuller as the Crystal Cathedral, the site required expensive renovations in addition to the $57.5-million purchase price.

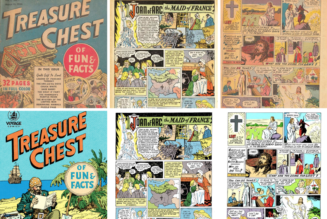

Nunn was one of those raising money for the church. She ran estate planning workshops and dealt with donors at the Orange Catholic Foundation. A nonprofit that supported the work of the diocese but was run independently, the foundation was one of many such organizations set up nationally following the clergy sex abuse scandal. Their purpose was to assure reticent donors that their contributions would go only to the specific church causes they designated and not for legal bills or settlements to victims.

A woman lights a candle inside the Christ Cathedral in Garden Grove.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Nunn had a talent for bringing in money, having raised about $5 billion for a variety of charities across the country over the course of her career, according to a declaration in the lawsuit against her. At gatherings of potential donors, she would use herself and her husband, Charles, as examples. We have six children, she explained, but our will leaves an equal share to a seventh — the church.

“She was a wonderful person to work with, so easy to be with and kind,” said Joe Pickett, a Catholic life insurance agent who volunteered at donor presentations.

When only two people showed up at a wills and trusts seminar at Our Lady Queen of Angels parish in Newport Beach, Nunn carried on. The attendees, both single men, ended up naming the foundation as the sole beneficiary of their estates, according to a court declaration by Donald Hunsberger, a former foundation board member.

Hunsberger, a Tustin attorney, recounted a presentation at what “many people would consider a barrio parish,” where a simply dressed, elderly couple approached Nunn for more information. The man turned out to be a successful engineer, and because of what Hunsberger described as Nunn’s “attention to the needs of every single person, no matter how humble in appearance,” the pair left $10 million to the foundation.

The nonprofit’s average bequest grew to an impressive $867,000. Though the foundation was separate from the diocese, the bishop served on its board of directors, and Nunn got to know and like him.

“Her comments about OCF, and Bishop Vann in particular, were always positive, encouraging and supportive,” Ricardo Brutocao, who shares a pew with Nunn at St. Timothy’s, wrote in a court declaration.

“She highly respected him,” said Bruckner, her daughter. “She was in shock when he did this.”

::

Their break goes back to the dark and uncertain early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic. The coronavirus had shut down churches, gutting weekly Mass donations, and out-of-work parents were unable to pay tuition at the diocese’s schools.

Bishop Kevin Vann, head of the Catholic church in Orange County, at a Mass to celebrate the opening and blessing of the Marian Gardens on the campus of the Christ Cathedral.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Vann needed an infusion of cash to navigate a predicted shortfall of $12 million, and he turned in March 2020 to the foundation, where Nunn was the interim executive director. The diocese’s chief financial officer asked for an emergency payout of roughly $2.6 million from specific endowments. The foundation’s board, a group of clergy and well-connected donors, consulted with its lawyers and determined that the state law governing endowments and the agreements with donors about how their money would be used did not allow such a transfer of funds.

Rebuffed, the bishop trained his displeasure on Nunn. Though she and the board subsequently used other avenues to raise about $1.5 million and turn it over to the diocese, he insisted that the board terminate her, according to court filings in the defamation suit and correspondence reviewed by The Times. Vann’s lawyers maintain in filings in the litigation that his frustrations with her stemmed from unrelated problems he saw at the foundation.

Nunn agreed to step aside, but on the day the board was to finalize her severance, Vann fired all but one of the 18 directors, citing “a loss of trust and collaboration.”

The axed directors were stunned, and some complained to the Vatican, to no avail. With her experience in church philanthropy, Nunn quickly found a job at a Catholic foundation in San Diego. The day after she signed her new employment contract, she sent an email to a Listserv of 47 Catholic foundation executives throughout the nation recounting the events in Orange County.

The subject line of the July 7, 2020, email was “You can’t make this stuff up.” She referred to the chief financial officer’s request for money as an attempt to “invade the endowment funds” and suggested the bishop’s mass firing of the board violated foundation bylaws.

“Is this considered a hostile take-over to distribute funds the diocese needs to cover debt? Lawsuits? Is this an overstep of authority? Is this the result of fatigue from the economic impact of the COVID crisis in addition to other financial stress? No one knows,” she wrote.

The note prompted a few sympathetic responses, including from an Oregon foundation administrator who described the situation as a “[w]orst nightmare scenario.” One from New York state told Nunn she should consider going to the California attorney general for help.

In the months that followed, the dust-up seemed to pass. Nunn started her job in San Diego, the old board accepted its vanquishment, and a new board chosen by the bishop installed a permanent executive director and moved forward with fundraising. (The new executive director wrote in a 2021 declaration that she had experienced no issues with Vann and said “it has been my impression that the Diocese honors, respects, and adheres to donor intent.”)

Vann, however, remained focused on the email. He saw it as an attack — not just on his reputation, but also on the “good name” of his parents, who raised him “to be honest and forthright, and always look out for the good of others,” he later wrote in a declaration in his suit against Nunn.

A procession begins during the opening and blessing of the Marian Gardens on the campus of the cathedral in Garden Grove.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

In October 2020, lawyers from the Costa Mesa firm Theodora Oringher filed a lawsuit against Nunn on behalf of the bishop and the CFO, Elizabeth Jensen. The complaint accused Nunn of libel and intentional infliction of emotional distress and demanded a retraction as well as a financial judgment, including punitive damages.

The suit opened quoting Jesus’ command to “love your neighbor as yourself.” Further in, it explained why the bishop was disregarding another famous Gospel instruction.

“The Bishop and Ms. Jensen carefully considered what would happen if they turned the other cheek,” the suit stated. “They have concluded that doing nothing in the face of these false statements would do immense damage to the needy. Specifically, if no one corrects the record, donors will not donate.”

Someone connected to the diocese subsequently sent a link to the lawsuit to the San Diego bishop, Nunn has alleged in court filings in the case. Her supervisor at the Catholic Community Foundation of San Diego then informed her that she would be fired if she did not retract her statements, she contends.

“When I refused on the grounds that any retraction would be a falsehood, I was, in fact, terminated from my employment,” she wrote in a declaration. “Thus is the strength and power of a Roman Catholic Bishop.”

She countersued the bishop and Jensen in 2021 for intentional interference of prospective economic advantage and other claims. They have denied wrongdoing.

Jensen, who now works for Goodwill of Orange County, did not provide answers to written questions from The Times. Her attorney, Andrew Prout, said in a statement that Jensen “must do everything in her power to preserve her exemplary record as a licensed financial professional.” Asked whether the diocese was footing her legal bills, her lawyer declined to answer.

At least seven attorneys from the Theodora firm have worked on the case for the bishop, including Chief Executive Todd Theodora. The firm billed clients $1,025 an hour for the work of a senior attorney, according to rates cited in an unrelated court ruling last year.

Vann’s legal team has taken an aggressive approach. When Nunn sued her insurers in federal court to try to force them to pay for her defense, his lawyers attempted to take over the fight. Drawing the deep-pocketed insurance companies into the matter could spell a much bigger settlement for the bishop down the line, and his lawyers argued to a judge that they had the resources to take on the companies.

Nunn, they wrote, was “an individual of modest means who lacks the resources and economic incentive to vigorously prosecute her coverage claims” while the bishop had “a full service law firm and its lawyers have decades of experience.”

Their motion to intervene was denied. Nunn has received about $283,000 from the insurance companies toward her legal fees, her lawyers said in a court filing.

Nunn lost an initial attempt to have the case thrown out under the California anti-SLAPP statute, which allows dismissal of a defamation suit if a judge determines it is a “strategic lawsuit against public participation,” meaning its intention is to intimidate or silence a citizen from speaking out about an issue of public interest.

But an appellate court reversed the ruling. Earlier this year, Thomas McConville, a different judge in Santa Ana, reviewed the evidence and sided with Nunn.

“Plaintiffs have failed to submit any competent evidence of Nunn’s purported ill will in making the subject statement,” the judge wrote. He said the original request by the diocese for $2.6 million from the foundation appeared improper and that Jensen “knew or should have known” the board could not hand over the funds she requested.

As for the bishop’s termination of the board, the judge wrote that he found no “evidence showing he had the authority to unilaterally remove the Board for the reasons he claims.”

The forceful dismissal of the case might have ended it once and for all; but about two weeks later, the bishop filed an appeal, ensuring the matter would stretch on for months and possibly years, and the legal bills on both sides would continue to climb.

Vann did not respond to questions about how his faith figures into the court battle. The diocese declined to identify friends or relatives who might offer insight on his behalf.

His decision to appeal prompted Bruckner, who works as a ministry assistant at a Colorado nondenominational church, to ask Pierre, the apostolic nuncio, to review the court record.

“Do bishops have unlimited resources,” she wrote in an email. “Where is God in this, the humility to extend grace, the kindness toward God’s people, the peace, the forgiveness?”

Pierre did not answer or respond to a message from The Times. In May, he delivered a commencement address at an Oregon seminary and called out to his “brother bishop” Vann, receiving a doctorate in ministry that day, telling the crowd, “I will be getting a full report from the administrators on what kind of a student the Bishop has been!”

::

Since the lawsuit, Nunn has sought jobs and consulting work in the Catholic community without success. She can no longer afford birthday gifts for her grandchildren, Bruckner said.

Her husband, who converted to Catholicism with her guidance in 2016, has been diagnosed with the progressive neurological disease Lewy body dementia. He requires close supervision, suffers from mood swings and anxiety and cannot offer her much emotional support, according to friends.

“What she’s going through, it just breaks my heart,” said Gina Cousineau, a San Clemente nutritionist who prays the rosary online with Nunn every morning. Another member of the rosary group, Diane Lopez of Brea, said, “She will not leave the church. She is planted in her faith.”

The litigation is little known among the faithful, but a handful of people aware of it expressed dismay.

“It’s the antithesis of Christianity,” said Anne Lanphar, a real estate lawyer who was a foundation volunteer when she met Nunn years ago. Of Nunn’s legal bills, which a court may order the bishop to pay, she said, “Can you imagine $1.9 million, what it could do for charities in the county?”

During Lent this year, Nunn was preparing doughnuts for the Sunday coffee hour at St. Timothy’s when the bishop walked into the kitchen. She told people he seemed taken aback, muttered, “Hi, Sue” and exited quickly.

The next morning, as she does every day, she logged onto her computer at 6:30, rosary beads in hand.

She and the others in her group prayed for specific causes: the sick. The poor. Peace. And the clergy.

As she does every day, Nunn asked God to bless the priests who serve the Diocese of Orange. The nuns. The deacons. And the bishop.