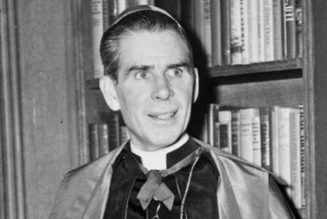

Who was the first person to forward written accusations about Theodore McCarrick to the police? Who was the first to pass them on to the apostolic nuncio?

The McCarrick Report gives us this shocking and very illuminating answer: McCarrick himself. And that is the principal explanation why “Uncle Ted” — right down to that very name — got away with so much for so long. He was so brazen in his behavior that it neutralized the reactions of so many.

Most attention to the McCarrick Report has focused on how ecclesial governance and clerical culture systematically failed to stop McCarrick’s rise. That is understandable, given that McCarrick himself has been defrocked and has disappeared from public view. While the attention focuses on who knew what when, some additional attention is merited to how McCarrick — the principal villain — did it. Without Ted McCarrick, after all, there is no McCarrick Report.

How did he do it? McCarrick never attempted to slink around in the shadows, lest he appear to have something to hide. He was more devilishly clever than that, figuring out that the best place to hide was in plain sight.

He groomed boys — though that term was not used in the 1970s — in front of their parents. The report includes the testimony of one mother who wrote anonymous letters to various prelates in the 1980s. (No records, originals or copies, of those letters were found.) She relates an incident in which McCarrick, sitting on the couch between her two sons, was massaging their inner thighs. This took place directly across the living room from her husband, who noticed nothing awry. McCarrick counted on just that dynamic. If “Uncle Ted” was being Uncle Ted in front of everyone and in plain sight, how could anything be really wrong?

About that “Uncle Ted.” It was not a private, confidential moniker, meant to throw a veil of secrecy over everything. McCarrick broadcast it far and wide, even hosting annual “Uncle Days” in his dioceses for all his “nephews.” If “Uncle Ted” was an official entry on the archdiocesan calendar, it had to be on the up-and-up, no?

The secondary villain of the McCarrick Report is Bishop Edward Hughes, McCarrick’s successor in Metuchen, New Jersey. He was singular, having direct firsthand testimony from priests who had had sexual encounters with McCarrick. (Nobody reported firsthand or secondhand knowledge of abuse of minors until 2017.) Bishop Hughes did not report what he knew, even when explicitly asked in the critical investigation of May 2000 before the appointment of McCarrick to Washington.

What McCarrick may or may not have done to induce Bishop Hughes’ silence is not in the report; Bishop Hughes died in 2012.

But with everyone else, the McCarrick modus operandi was to be so brazen that, no matter how strange the behavior, people would assume that because he was not hiding it, there must be some possible innocent explanation. Again, it was devilishly clever. That’s how he proceeded with various New York families in the 1970s.

And that’s the story of the infamous beach house on the Jersey shore.

All the accounts tell the same story: McCarrick would invite a half-dozen seminarians and there would be one bed short, leading to the unfortunate ultimate being coerced into sleeping in the same bed with the archbishop. The remarkable fact, though, is not the shortage of beds, but the abundance of seminarians. McCarrick did not try to keep this low-key; it was out in the open. Dozens and dozens of seminarians saw it take place over the years. In the hothouse environment of a seminary, it was well discussed.

Consider how one of the secondary heroes of the McCarrick Report, Father Boniface Ramsay, put it. Father Ramsay would eventually write to the apostolic nuncio after McCarrick was transferred to Washington with his reports about the same-bed sleepovers. He wrote the following in 2019, relating how in the late 1980s and early 1990s he taught at the Newark seminary where the sleepovers were well known:

“Whenever a seminarian who had slept in the same bed as McCarrick shared his experience with a faculty member, the common response was ‘Did he touch you?’ As I search my memory for what happened thirty years ago, this may very well have been my response, too. I never heard that McCarrick touched anyone. Since there was no touching and concepts like sexual harassment and abuse of power were rather unfamiliar at the time, and since there was no precedent for how to deal with an archbishop who slept with his seminarians but didn’t touch them, there seemed nothing to do but to accept this unusual behavior.”

Father Ramsay continued:

“It must be emphasized here not only that sexual harassment and abuse of power were things people worried less about back then, but also that no one at the time knew anything of the allegations of child abuse that would be made against McCarrick and revealed by The New York Times in June [2018]. There was only his unusual behavior with seminarians, which seemed to be accepted by everyone.”

It was “accepted by everyone” because McCarrick never made the slightest effort to hide it. His secretary made the arrangements. When asked about the practice, McCarrick would explain it as innocent, if imprudent. The McCarrick Report reveals that he stopped the practice in 1996 overnight, as it were, when Cardinal John O’Connor of New York told him that it had to end because too many people were talking about it.

Over the years, McCarrick would write about the “imprudence” of the sleeping arrangements to the apostolic nuncio, the prefect of the Congregation of Bishops and even to St. John Paul II himself. But he was even more brazen than that. Noting that he ordained more priests than any other bishop in the nation — likely one of the things that attracted favorable attention from John Paul — he argued that his avuncularity precisely created the familial environment that promoted vocations, even if “imprudent” when noticed by outsiders. The McCarrick letters of explanation are dumbfounding in their shamelessness; the sleepovers were not a bug, but a feature!

McCarrick in effect gave himself an auto plea bargain. He would cop to the innocent, imprudent, avuncular “chaste” sleeping arrangements as a means to avoiding any attention being paid to his abuse of minors or predatory behavior with seminarians and priests. And it worked in a fiendish way.

For the most part what “everyone knew” about McCarrick was that he had a strange, even creepy, habit but also led the nation in priestly ordinations.

McCarrick’s brazenness went even further. In 1992 and 1993 there were a series of anonymous allegations about his sexual misconduct sent to various U.S. cardinals and the apostolic nuncio. (These were received and recorded, casting doubt on whether the mother’s similarly anonymous letters in the 1980s actually reached the prelates she intended.)

What did McCarrick do, faced with the danger that he would be exposed? He doubled down. He wrote to the cardinals who got the anonymous letters, he wrote to the nuncio to notify him, he convened his priests’ council to tell them about it, and he shared the information discreetly with “friends in the FBI and police” who could apparently look into who was sending them. It was more or less what one would expect from an innocent man desirous of clearing his name. And it worked again. Until 2017, when the Archdiocese of New York set up an independent compensation fund for sexual-abuse victims, the only time the civil authorities were notified about anything potentially amiss was from McCarrick himself.

Going further still, in the aftermath of the false sexual-misconduct allegations against Cardinal Joseph Bernardin of Chicago — which set off a global media frenzy — McCarrick spoke indirectly about the anonymous allegations, saying that he too had been “falsely accused.”

Eventually the priests known to Bishop Hughes who had been molested pursued their claims, leading to diocesan settlements in 2005, the year McCarrick turned 75. The jig was finally up? Yes and no.

He was told by Pope Benedict XVI to leave office after Christmas 2005; he dithered until after Easter 2006. He asked for his retirement and the appointment of his successor to be announced simultaneously, so that it would appear that nothing was amiss, even though he was being shown the door precisely because something was amiss. He was shameless, counting on the fact that his utter, unremitting, unrelenting, uncompromising shamelessness would lead many to conclude that there must not be anything to be ashamed about. It was a perverse performance by a perverted priest, perseveringly perfected over decades.

An illuminating bit from the McCarrick Report is that the McCarrick files at the nunciature in Washington are so voluminous that they had to be set apart on their own, the equivalent, one official noted, of what three dioceses would generate. These are not the diocesan files, mind you, but McCarrick’s personal correspondence. He wrote constantly to the nuncio, updating him on every trip, every award, every honor. Two or three could not gather with McCarrick without the nuncio being informed.

Archbishop Pietro Sambi at one point wrote to Rome that he did not want McCarrick “at his door” every day. The avalanche of letters was quite enough. It was part of McCarrick’s cunningness.

When told by Cardinal Giovanni Battista Re, prefect of bishops, to keep a “low profile” and to travel less, McCarrick would not only make himself omnipresent, but send detailed reports about his activities. He refused to play the role of the guilty party, acting always like an innocent man who had nothing to hide. Would a guilty man record every jot and tittle in letters to the nuncio?

In effect, he dared someone to bring down the hammer on him, always providing a smidgen of ambiguity here, a touch of uncertainty there; there was always a possible (if not plausible) alternative explanation to delay his day of reckoning.

Combined with his frenetic work ethic, his fundraising support of various good causes, including the Papal Foundation, his gift-giving, his success in priestly vocations and his extraordinary role in St. John Paul II’s return of Our Lady of Kazan to Russia, the shameless one began to convince a good number of otherwise sage people — laity and clerics alike — that he was an innocent man, if not a saintly one.

Those who were fooled — with the particular exception of Bishop Hughes, who was not — bear responsibility for not sensing that a man that shameless might be shameful too. But that was McCarrick’s strategy to deal with suspicion, and, tragically, he very nearly pulled it off to the end.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity

![Los Angeles DA George Gascon suspends prosecutor for ‘misgendering’ and ‘deadnaming’ trans child molester accused of murder [warning: autoplay video]…](https://salvationprosperity.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/los-angeles-da-george-gascon-suspends-prosecutor-for-misgendering-and-deadnaming-trans-child-molester-accused-of-murder-warning-autoplay-video-327x219.jpg)