The Western world is the creation of the Church, and the crisis of the West is always at bottom the crisis of the Church. This is especially so where the Church has receded into the background of the Western mind – where men’s plans are hatched in the name of progress, science, social justice, equity, or some other purportedly secular value, and make little or no reference to religion. For liberalism, socialism, communism, scientism, progressivism, identity politics, globalism, and all the rest – this Hydra’s head of modernist projects, however ostensibly secular, is united by two features that are irreducibly theological.

First, they are all essentially apostate projects, enterprises that have arisen in the midst of Christian civilization with the aim of supplanting it. And they could have arisen only within the Christian context, because, second, these projects are all heretical in the broad sense of that term. That is to say, they are all founded on some idea inherited from Christianity (the dignity of the individual, human equality, a law-governed universe, a final consummation, etc.) but removed from the theological framework that originally gave it meaning, and radically distorted in the process.

As an essentially apostate and heretical phenomenon, modernity is also an Oedipal phenomenon. Its series of grand, mad schemes amount to the West fitfully seeking – now this way, now that – finally to free itself from the authority of its heavenly Father and to defile the doctrine of its ecclesiastical Mother. And in the process, the would-be parricides always make themselves over into parodies – remolding the world in their image, suppressing dissent, and otherwise acting precisely like the oppressive God and Church that haunt their imaginations.

Eric Voegelin (1901-1985) was among the most important thinkers to analyze modernity under the category of heresy, and the specific heresy he regarded as the key to the analysis was Gnosticism. The Gnostic heresy is one that has recurred many times in the long history of the Church, under various guises – Marcionism, Manicheanism, Paulicianism, Albigensianism, Catharism, and so on. Like Hilaire Belloc, Voegelin regarded Puritanism as a more recent riff on the same basic mindset. And he argued that modern ideologies like communism, National Socialism, progressivism, and scientism are all essentially secularized versions of Gnosticism. Voegelin’s best-known statement of this thesis appears in The New Science of Politics, though he revisited and expanded upon it in later work.

Now, what Voegelin saw in these ideologies is manifestly present in Critical Race Theory and the rest of the “woke” insanity now spreading like a cancer through the body politic. But it is also to be found in certain tendencies coming from the opposite political direction, such as the lunatic QAnon theory. Voegelin’s analysis is thus as relevant to understanding the present moment as it was to understanding the mid-twentieth-century totalitarianisms that originally inspired it. It reveals to us the true nature of the insurgency that is working to take over the Left, and will do so if more sober liberals do not act decisively to check its influence. But it also serves as a grave warning to the Right firmly to resist any temptation to respond to left-wing Gnosticism with a right-wing counter-Gnosticism.

Notes of the Gnostic mindset

The Gnostic mentality – considered at a high level of abstraction that leaves out the many differences between the various specific Gnosticizing movements that have arisen over the centuries – can be characterized in terms of tendencies like the following:

First, it sees evil as all-pervasive and nearly omnipotent, absolutely permeating the established order of things. You might wonder how this differs from the Christian doctrine of original sin. It differs radically. Christianity teaches the basic goodness of the created order. It teaches that human beings have a natural capacity for knowledge and practice of the good – the idea of natural law. It teaches that basic social institutions like the family and the state are grounded in the natural law, and are therefore good. To be sure, it also teaches that original sin has massively damaged our moral capacities and social life. But it has not obliterated the good that is in them. And its damage has been mitigated by special divine revelation since the beginning of the human race, as recorded in scripture. The Gnostic mindset takes a much darker view. The original Gnostic movements regarded the material world as essentially evil. They saw marriage and family as evil. They regarded the God of the Old Testament as the malign creator and ruler of the present sinister order of things. The Gnostic mentality is thus one of radical alienation from the created order. It sees that order as something to be destroyed or escaped from rather than redeemed.

Second, the Gnostic mentality holds that only an elect who have received a special gnosis or “knowledge” from a Gnostic sage can see through the illusory appearances of things to the reality of the incorrigible evil of this world. You might wonder how this differs from Christian appeal to special divine revelation. Once again, the difference is radical. Christian teaching is essentially exoteric. Christianity holds, first, that at least the basic truths of natural law and natural theology are available in principle to everyone and at any time, just by using their natural rational powers. Second, it holds also that even special divine revelation is publicly available to all, and backed by evidence that anyone can examine, viz. the evidence that a prophet claiming a revelation has performed genuine miracles. Gnostic teaching, by contrast, is esoteric. It holds that the truth cannot be known from the appearances of things or from any official sources, but has been passed along “under the radar” and is accessible only to the initiated. The Gnostic epistemology is what today would be called a “hermeneutics of suspicion.”

Third, the Gnostic mindset sees reality in starkly Manichean terms, as a twilight struggle between the sinister forces that rule this evil world and those who have been “purified” of it and armed with gnosis. Once again, you might think this differs little from Christian teaching, but once again you’d be wrong. Christian doctrine holds that natural reason and natural law provide common ground by which the Christian and the unbeliever can debate their differences and cooperate in pursuing common ends. And it holds that the righteous and the wicked – the wheat and the tares – will in any event always be intermingled in this life, to be separated only at the Last Judgment. The Gnostic mindset is not interested in such common ground or tolerant of such differences.

Fourth, the Gnostic lives in what Voegelin calls a “dream world.” This is inevitable given the subjectivism and irrationality entailed by the Gnostic’s esotericism, and the paranoia entailed by his Manicheanism. The Gnostic sees the manifestation of evil forces everywhere. He inverts common sense and everyday morality, seeing these as reflective of the evil order of things and the sinister forces behind it. Nothing that happens is taken to falsify his beliefs, because any bad effects are interpreted as merely further manifestations of the evil forces, rather than reflecting any defect in the Gnostic’s belief system. Voegelin writes:

The gap between intended and real effect will be imputed not to the Gnostic immorality of ignoring the structure of reality but to the immorality of some other person or society that does not behave as it should behave according to the dream conception of cause and effect. (The New Science of Politics, pp. 169-70)

Fifth, Gnostic moral practice veers between the extremes of puritanism and libertinism. Initially this might seem puzzling, but it makes perfect sense given the Gnostic’s other commitments. On the one hand, given the Gnostic hatred of the created order and of conventional moral and social life, what the normal person takes to be permissible or even necessary to ordinary life is prissily condemned. Hence, Gnostic heretical movements over the centuries famously emphasized vegetarianism, pacifism, the purported evil of capital punishment, and similarly utopian attitudes, pitting the “mercy” of a Gnosticized interpretation of Jesus against what they regarded as the sinister Old Testament God of justice. On the other hand, since the material world is taken by the Gnostic to have no value, nothing that happens within it ultimately matters, and the most licentious behavior can be excused. Hence, sexual immorality was often tolerated in practice – as long as it was not associated with marriage and procreation, which would tie us to the ordinary material and social order.

Sixth, the Gnostic posits a final victory of the “pure” over the evil forces that govern everyday reality. For Gnostic heretical movements of the past, this entailed an ultimate release from the material world. But the modern political successors of Gnosticism tend to be materialist, seeing no hope for a life beyond this one. Here is where Voegelin sees the greatest difference between ancient and modern forms of Gnosticism. As Voegelin famously put it, modern forms of Gnosticism “immanentize the eschaton” – that is to say, they relocate the final victory of the righteous in this world rather than the next, and look forward to a heaven on earth.

Modern Gnosticisms

The many variations on the Gnostic heresy that arose in the ancient and medieval worlds did so in a context where the reality of the supernatural was taken for granted. The influence of classical philosophical traditions like Neo-Platonism and the dominance of the Church made this reflexive supernaturalism possible. But the Enlightenment radically changed the basic cultural situation, breaking the power of the Church over Western civilization and putting Western philosophy and intellectual life in general on a trajectory toward naturalism.

Voegelin’s deep insight is that this by no means destroyed the Gnostic mindset, but merely transformed it. Gnosticism didn’t disappear with the decline of supernaturalism; instead, it adapted to the new cultural situation by naturalizing itself. “Immanentizing the eschaton” is the most obvious adaptation, but all the other elements of the Gnostic mindset were also transformed in various ways in the different modern forms of Gnosticism.

Hence, consider Marxism from the point of view of Voegelin’s analysis. Here the all-pervasive and near omnipotent evil that the Gnostic sees in the world becomes capitalism and the bourgeois power that it sustains. This power is taken to permeate every aspect of life, on the Marxist analysis, insofar as the legal, moral, religious and general cultural “superstructure” of society are all held to reflect the capitalist economic “base.” Everyday moral assumptions are mere ideologies that mask the interests of bourgeois power, religion is a mere opiate to reconcile the oppressed to that power, and so on. Marxist theory is the gnosis that reveals this dark and hidden truth about the world, and Marx, Engels, Lenin and Co. play the role that Gnostic sages like Valentinus, Marcion, and Mani did in the Gnosticisms of the past. The Manichean roles of the forces of darkness and of light are played by the bourgeois oppressor on the one hand, and the proletariat and its intellectual vanguard on the other.

The Marxist position is made as subjectivist and unfalsifiable as that of earlier Gnostics to the extent that criticism of the Marxist analysis is dismissed as an ideological mask for bourgeois power, and the critics are tarred as “objective allies” of that power (even when they happen to be left-wing themselves). The paradoxical puritan/libertine dynamic is evident in the moralistic rejection of bourgeois moral norms. The final victory over evil – the “immanentized eschaton” – is the realization of communism, in which exploitation will disappear, alienation will be overcome, the state will wither away, and liberated man will (as Marx famously put it) “hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, [and] criticize after dinner.”

Or consider the analysis of Nazism as a kind of Gnosticism. Here it is the Jews who are cast in the role of omnipotent villain, portrayed in Nazi propaganda as the puppet masters behind capitalist exploitation and communist oppression alike, and as alien and subhuman parasites who subvert the health and moral order of the German nation. The gnosis that claims to reveal this is the teaching of the Führer. The Führer and the Aryan people he leads on the one hand, and the Jews and their allies on the other, play the familiar Manichean roles. The cultural relativism of Nazi ideology gives it an essentially subjectivist and irrationalist character. The libertine/puritan dynamic finds expression in the Nazi’s contempt for ordinary notions of justice and rights on the one hand, and an austere ethos of self-sacrifice for the German Volk on the other. (See Claudia Koonz’s book The Nazi Conscience for an illuminating account of Nazi pseudo-moralism.) The Nazis’ own depraved “immanentized eschaton” involved the “Final Solution” and the “Thousand Year Reich.”

Woke Gnosticism

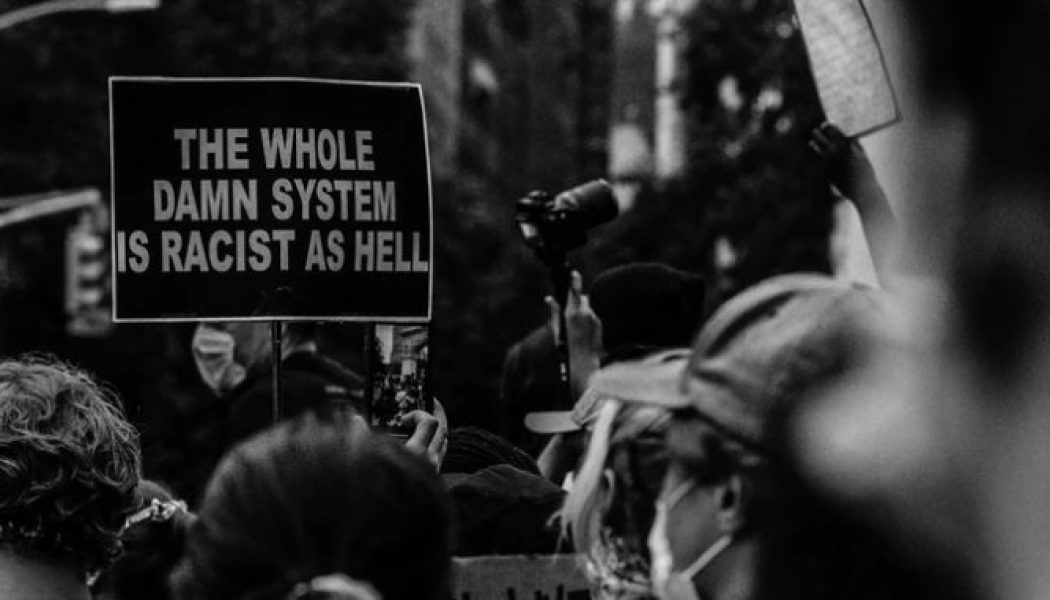

Critical Race Theory (CRT) is in exactly the same mold. The difference is that, unlike Marxism and Nazism, it has not (yet?) been implemented as a political program. But the ravings of an Ibram Kendi or Robin DiAngelo manifest the same paranoia, irrationalism, and Manichean fanaticism as any other form of Gnosticism. And CRT’s violent implications have already been seen on the streets of Washington, Portland, Seattle, Minneapolis, New York, Kenosha, and other American cities during the summer of 2020 – an echo of Gnostic mobs of the past (SA Brownshirts, Young Maoists, and the like) and a foretaste of things to come.

For CRT, the all-pervasive and near omnipotent source of evil in the world is the “racist power” of “white supremacy,” “white privilege,” and indeed “whiteness” itself. This racism is “systemic” in a Foucauldian sense – it percolates down, in capillary fashion, into every nook and cranny of society and the unconscious assumptions of every citizen. It is especially manifest in all “inequities,” which result from the “implicit biases” lurking even in people who think of themselves as free of racism. And it is to be found even in the most seemingly innocuous of offenses, which are in reality “micro-aggressions.” Even self-consciously “anti-racist” CRT adepts themselves are not free of racism, but must constantly engage in a Maoist-style self-critical struggle to root out and confess ever deeper and unexamined racist assumptions.

In CRT, this imagined totalitarian “white supremacy” plays the role that the God of the Old Testament does in the original forms of Gnosticism, that the bourgeois does in Marxist theory, and that the Jews play in Nazi mythology. It is the devil figure on which every misfortune can be blamed and to which every hatred and resentment can be directed, the bogeyman lurking under every bed and in every shadowy corner, waiting to terrorize. Indeed, as critics of CRT point out, if you take a work of Critical Race Theory and replace terms like “whiteness” and “white supremacy” with “Jewishness” and “Jewry,” the result reads chillingly like a work of Nazi propaganda.

Other forms of woke Gnosticism have their own bogeymen – “patriarchy,” “heteronormativity,” etc. – which, like “whiteness,” are abstractions spoken of as if they were concrete demonic powers. And just when you thought you’d heard of every kind of “oppression” imaginable, the Critical Theorists come along with the notion of “intersectionality,” by which ever more exotic forms can be fantasized into being. For example, if you are a transgender lesbian woman of color, you suffer a special kind of oppression – one defined by the “intersection” of oppressions suffered by each of the groups to which you belong – that is different from the kind suffered by (say) a gay immigrant with disabilities. (Wokesters don’t play the victim card; they play a whole 52 card deck.)

The gnosis that purportedly reveals all of this suffocating oppression is to be found in the writings of gurus like Kendi and DiAngelo, whose main difference from the likes of Marcion and Mani is the size of their royalty checks. Their books are almost entirely free of any actual argumentation. There is, instead, page after tedious page of sheer tendentious and question-begging assertion, with all disagreement preemptively dismissed a priori as “racist,” the expression of “white fragility,” and so on. CRT claims are textbook examples of Popperian unfalsifiability: Everything is interpreted as evidence for them, and nothing is permitted to count as evidence against them.

Of course, there really is racism in the world, just as capitalists really do sometimes exploit their workers. And such racism ought indeed to be condemned. Naturally, CRT authors do cite some actual examples of racism. But that racists exist comes nowhere close to establishing the entire paranoid CRT worldview, any more than the existence of exploitative capitalists suffices to establish the truth of Marxism.

It is no accident that CRT adepts think of themselves as “woke.” For it is not rational argumentation that compels them but a kind of conversion experience, and Kendi, DiAngelo, et al. are essentially Gnostic preachers rather than philosophers or social scientists. Their reliance on inflammatory rhetoric, preemptive dismissal of all criticism as racist, and insistence on putting the most sinister imaginable interpretation on every aspect of social life, create a “dream world” of exactly the kind Voegelin describes. As Greg Lukianoff has noted, “wokeness” inculcates distorting and paranoid habits of thought of precisely the sort that Cognitive Behavioral therapists warn their patients to avoid.

The Gnostic libertine/puritan dynamic manifests in the shrill condemnation of traditional institutions and morals as oppressively “racist,” “sexist,” “homophobic,” etc. – which gives license both to violate existing norms in the name of “social justice,” and self-righteously to condemn and “cancel” anyone who objects. The Manichean element is manifest in Kendi’s notorious insistence that there is no “non-racist” neutral middle ground. You must either be “anti-racist” in Kendi’s understanding of that term, or you are a racist. In general, the “woke” or “social justice warrior” mentality is absolutely intolerant of nuance or dissent. You are either on their bandwagon, or you are part of the “racist,” “sexist,” “homophobic,” etc. enemy. The immanentized eschaton of the wokester is a radically egalitarian world that has been purified of every last trace of “inequity,” “racism,” “sexism,” “homophobia,” etc., whether in deed or in thought. Though, since there are always new and ever more exotic strata of “oppression” to be identified and confessed to, that eschaton is very far off indeed.

A war of Gnosticisms

With wokeness suddenly flooding universities, high schools, the medical profession, the military, business, and seemingly everywhere else, we are seeing something comparable to the Arian crisis of the 4th century or the Albigensian crisis of the 13th century – the alarmingly rapid spread of a toxic religious cult that threatens the general sociopolitical order no less than it does the Church. As in these earlier crises, there are many Christians, already heterodox anyway, who are happy to cave in to the madness. And there are also some otherwise orthodox Christians who, out of cowardice and/or muddle-headedness, try to accommodate themselves to it. In the secular context, we see a similar dynamic among conservatives.

But the vast majority of orthodox Christians and of conservatives see the insanity for what it is, and are alarmed by it. Applying Voegelin’s analysis, which I think reveals the true nature of the phenomenon, shows that they ought to be very alarmed by it. But Voegelin’s analysis also shows how not to respond to the crisis – namely, with any sort of counter-Gnosticism. Yet the bizarre QAnon phenomenon on the Right appears to be exactly that. It has all the key marks of the Gnostic mindset – the positing of unseen malign forces, the hermeneutics of suspicion and “dream world” theorizing, Manicheanism and shrill intolerance of all dissenters, even something like an immanentized eschaton (“The Storm”).

In the long run, Critical Race Theory and other forms of “wokeness,” though not much more intellectually substantive than the QAnon lunacy, are manifestly far more dangerous, given their pseudo-academic nature and appeal to the temper of mainstream opinion. Again, “woke” ideas now pervade media, universities, high schools, churches, corporate board rooms and HR departments, and on and on – the commanding heights of the mainstream social and economic order. QAnon, by contrast, while having some mass appeal, extends no higher up among those with power and influence than a handful of crank lawyers and congressmen. And unlike CRT and the other elements of wokeness, it has no intellectual lineage or cultural framework that could give it the heft to extend much farther than that. Here’s the acid test: Few Republican politicians want to associate themselves with QAnon. But few Democratic politicians dare to disassociate themselves from CRT and other forms of wokeness. That shows you which of these warring Gnosticisms has the upper hand.

All the same, in its short life, the QAnon madness has already caused enormous harm, both by rotting out minds and by playing a role in both the Republican loss of the Georgia Senate elections and in the breach of the U.S. Capitol. And as the history of Weimar Germany teaches us, a war of Gnosticisms does not end well.

Gnostic woke madness will not be remedied by aping it. On the contrary, more than ever, what the times call for is conservative sobriety. And orthodoxy. Heresies not only aim to subvert the Church, but they fill the vacuum that opens up when the Church loses its self-confidence, its fidelity to its traditional teaching, and its sense of mission – and as a consequence, loses its attractiveness. The crisis of the West is the crisis of the Church. The West will not be restored to health until the Church is restored to health. And that is a project that requires us to see beyond election cycles, and indeed beyond politics.

(This essay originally appeared in slightly different form on Dr. Feser’s blog and is reposted here with kind permission of the author.)

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity