Over the past few years especially—though this has been going on for some time—‘pastoral’ has meant the approach at the other end from ‘doctrinal’ on some fictional spectrum. For those who speak the newspeak as their everyday lingo, the goodies are at the pastoral end of the spectrum and the baddies are at the other end. The ‘pastoral’ approach is that which never withholds Holy Communion from pro-abortion politicians, never addresses public sin, never corrects liturgical abuses, never condemns heresies, never seeks to fix the problem of irregular unions—essentially, the ‘pastoral’ approach never protects the flock. Indeed, to be truly pastoral, according to newspeak, you must do the opposite of what a pastor would do. In turn, one cannot expect to be both a shepherd of souls and ‘pastoral.’

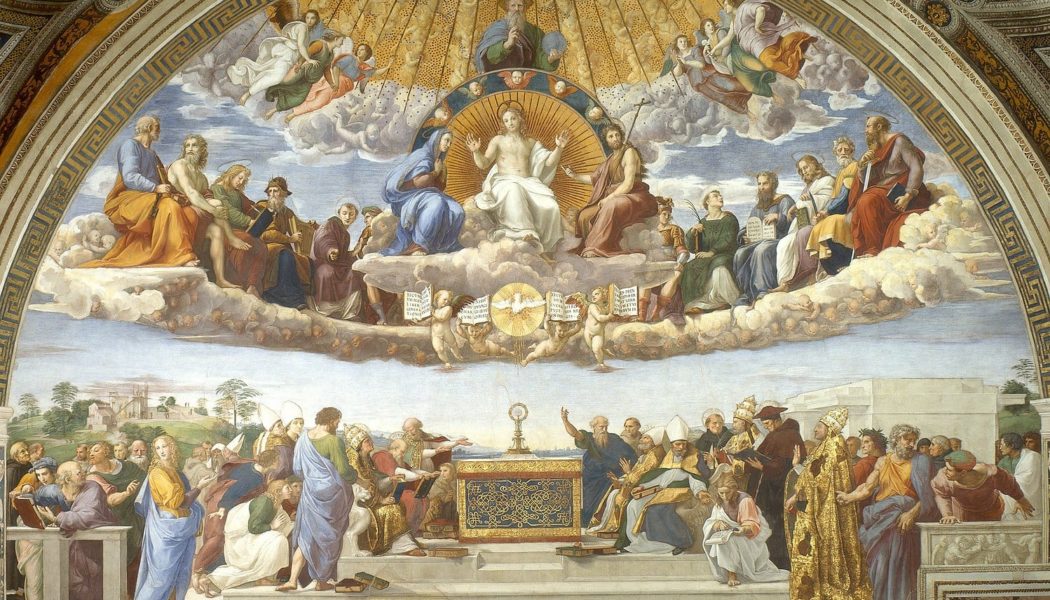

I am still at times caught off my guard and can find myself amazed at how ‘pastoral’ is used. I will never forget visiting a friend, a monk, at his priory in East London. The priory had been a Franciscan friary, then run by a diocesan priest for a while before his Order took it over. The monks had decided to pull down the plasterboard covering the walls of the priory church which had been put up in the late 1960s, to reveal the glorious stone reliefs depicting the lives of Francis and the early Franciscan saints. The newly arrived monks knew the reliefs were there from old pre-conciliar photos of the church. Having pulled down the plasterboard they discovered that the Franciscans, before whitewashing the church and hiding the images of their seraphic fathers, had taken hammers and smashed the face off each image. I visited my friend just after the plasterboard had come down, and the vision was harrowing. It was as if I had arrived just as Oliver Cromwell had left. I turned to my friend, expressing my shock at how any friar could have done this. He replied, “Soon after Vatican II, one of the Franciscans here went off to Rome to undertake a course in pastoral liturgy, and on his return instructed the other friars to correct the church; it was felt that this would be more pastoral.” Sacred art, is of course, literally pastoral, since it possesses a catechetical character, forming the faith of the faithful. In the world in which ecclesiastical newspeak is spoken, however, the smashing of such a pastoral resource is ‘pastoral.’

There has been an interesting redefining of the word ‘ministry’ by ecclesiastical newspeak. The term is often used when Church leaders seek to cover up their failure to fulfil anything close to what the Great Commission requires (Matt. 28:16-20). In the face of great scandals, when the ankles of Church leaders go wobbly, we hear about the importance of being engaged in a ‘ministry of openness to the world,’ a ‘ministry of progress,’ a ‘ministry of learning,’ or a ‘ministry of listening,’ a ‘ministry of questioning.’ This all sounds very humble, but it is the talk of a demoralised Church proclaiming to the world that it really has nothing to teach—it has nothing to say because it has no answers. Of course, it is not humble at all. Anything the Church has to give it has received from its Head, and so really such talk marks the refusal to recognise that Jesus Christ has given to His Bride the Church all that is needed to fulfil her mission, if only her servants would believe it.

I was once at a national conference for catechetical formators, during which one leading lay employee of the Church claimed that parishes needed to develop a ‘ministry of hugs.’ I do not know exactly what he meant by this. Whatever it was, something tells me that such a ‘ministry’ might be problematic under legislation for the protection of vulnerable persons. In any case, what amazed me was how easily newspeakers could equivocate on the term ‘ministry,’ perhaps making it the most dangerous of all newspeak terms. Whatever ‘ministry’ now means, it does not mean ministry. It is not participation in the work of a minister of religion, at least if religion is not to be emptied of its entire content. No, this is the opposite of ministry; it is the confession that the Church, as her members popularly understand her in our current age, has nothing to give, nothing to say, and, essentially, no ministry at all. If ministry entails, as Catholics always believed, governing, teaching, and sanctifying the faithful, then the ‘ministry’ of ecclesiastical newspeak entails a tacit dissolving of the these duties.

There are of course other terms that may be criticised along the same lines. One I often heard was ‘extreme,’ used for anyone who is seen as taking the Catholic Faith too seriously. I once found myself talking with a man at a conference; he was an employee of a diocese in the north of England and his job was to assess the degree and quality of religious practice in Catholic schools throughout his diocese. This man described to me a ‘crisis’ in the diocese that had arisen due to a number of younger clerics who were, he informed me, ‘extreme.’ I asked questions, trying to get a sense of the exact nature of their extremism. Eventually it came out that these young priests believed in, and had preached about, the doctrine of the real presence of the eucharist. For teaching a doctrine that is at the centre of the Faith, these priests were deemed to be extremists.

All these terms mean in newspeak the opposite of what they mean in the vernacular. The question is, where has this newspeak come from, and what is the reason for its emergence? I think this language has arisen out of necessity, due to the practical concordat that now exists between the Church and the post-Christian world. The Church currently begs the unconverted world for at least the religious freedom necessary for its subsistence, and the Church in turn promises to keep out of temporal affairs. The Church can be free, but for her freedom her leaders swear never to make of any nation a disciple. This arrangement will of course never procure liberty for the Church, simply because of the inherent enmity between the unconverted world and the Church. In any case, it is for the discipling of all nations that the Church was established, and so this concordat renders the Church pointless.

This situation puts the Church in a very difficult position. The Church must give the impression to her members of doing that for which she was established, whilst not doing it. In turn, the Church needs a language which sounds ‘churchy,’ is adequately deceptive, gives the impression that she is working in continuity with the past, but that bestows on her a purpose altogether different to her real purpose. Thus, Catholics find themselves in a bizarre Orwellian Church, with Church officials ever speaking the prescribed newspeak, slipping these terms into every other sentence in the hope of not being charged with the career-ending accusation of ‘extremism,’ which would be forthcoming were any to fall back on the language with which the Church has traditionally expressed herself. This is not altogether deliberate, and the speakers of newspeak are not liars, for liars know they are lying. These people are fakes, to use Roger Scruton’s well-known distinction. Fakes lie, but are themselves taken in by the lies, believing all the lies they tell. Were their fakery to be exposed as such, they would be as shocked as anyone else.

Catholics are surrounded by the upside-down chatter of ecclesiastical newspeak, and it is here to stay, that is, until a rediscovery that the Church derives her purpose from the Great Commission—the mandate to make disciples of all nations, and this cannot be substituted. Ecclesiastical newspeak is with us by necessity, expressing the Church’s new fake role in the world, that is, a Church which does not call the unconverted world to Christ, but ‘accompanies’ the world as it remains as it is, rapidly conforming herself to it, rather than vice versa.

Ecclesiastical newspeak, always meaning the opposite of what it appears to mean, is necessary for a Church that does the opposite of what it purports to be doing. Catholics were promised a Synod on the Family, and they were given endless discussions about divorce and homosexuality. They were promised a Synod on the evangelisation of the Amazon, and they were presented with the Rousseauan fantasies of eccentric Germans and the worship of fertility gods. More recently, they were promised greater Church cohesion, and were given a plan for the persecution of Catholics attached to the traditional liturgy.

The combination of the inordinately optimistic anthropology, that is now so ubiquitous in the Church, with a language designed to prevent proper expression of the Faith has turned catechesis into an intellectual and devotional wasteland. It is increasingly difficult for Catholics to speak of the salvation of man, because they have emptied both their vocabulary and their anthropology of the content which makes sense of Christ’s salvific mission. It is here that I must turn to the traditionalist movement, for therein I see a solution to this crippling malaise. I shall briefly focus on two aspects of the traditionalist movement which I think offer an immediate remedy: the traditional Catholic family as a catechetical school, and the integrated character of traditional Catholic life.

One of the reasons the catechising of young people has become so problematic today is that Catholic parents believe that catechesis is to be undertaken by the parish lay ministry team, along with the Catholic school to which they may or may not send their children. The role of the parents in their own minds, therefore, is understood to be that of the car driver. They must get their children to and from catechetical input by others, but they have no catechetical role themselves. The identity of parents as the primary catechists has been largely, if not wholly, eclipsed.

One of the mysterious features of the traditional Catholic family is that, despite usually having access to very good priests, whose catechetical instruction they can trust, they nonetheless catechise their children themselves, seeing the catechetical role of the priest to be supplementary. At one traditional parish I know, each Sunday the priest spends twenty minutes after Mass with the young children and their parents, offering some aspects of the Faith to consider at greater depth at home. The priest sees his role as that of providing some supplementary input, but the real catechising is to be done by the parents within the ‘domestic church.’ Rather than ‘accompanying’ the parents, as the newspeakers would have it, the priest actually accompanies them.

This approach stems in part from a general independence of mind which is found among traditionalists—which is now causing great alarm among the bullies in the Roman curia. Traditionalists know well that to which they are bound, and those things with which they have liberty, and it is this general independence which has enabled them to move outside what is now deemed mainstream Catholicism. For this reason, traditional Catholic families are often attracted to home-educating, creating an environment in which the children can be protected from the highly noxious ideas widely circulating, as well as integrate into their home-schooling catechesis and prayers throughout the day.

Traditional Catholic parents often grasp the obvious connection between the content of catechesis and the liturgy for which they have opted, the traditional Latin (or ‘Tridentine’) mass. In the pseudo-catechetical self-esteem course of the local parish, the intrinsic connection between the life of grace and the sacrifice of the Mass is generally left unexplored. One friend of mine was in an unusually active ‘mainstream’ parish for twenty years—one that atypically put great emphasis on parish catechetical instruction—and yet never was the Mass presented as a sacrifice; rather, the Mass was exclusively seen as a gathering of the community. This is an error that is not present within the traditional movement.

This brings me to the second point, namely the integrated character of traditional Catholic life. One of the remarkable characteristics of ‘mainstream Catholicism’ is the sheer extent of its fragmentation. Going to Mass is seen as one religious thing that the family does, a family activity to which they devote an hour each weekend, unless it conflicts in the diary with another activity. The Faith is often implicitly presented as low on the hierarchy of priorities, and throughout the week emphasis is placed on school achievements, sports, friendship groups, television time, and so forth. Religion is reserved for Sunday mornings, if it is convenient. If some moral issue is discussed around the dining table, generally the parents will side with the position advanced by the surrounding culture, even if wanting to convey some reservations on extreme issues such as abortion. On same-sex unions or divorce, however, the parents will usually express their desire for the Church to ‘catch up with the times.’ This picture shows the fragmentation only at the surface level. Morality, intellectual life, culture, family, the Faith, all have their little slots on the hierarchy of values, quite cut off from one another, with the Faith somewhere toward the bottom—uniting them all is the surrounding culture as primary teacher, conforming any given category to its own commitments.

Generally speaking, in the traditional Catholic family, the culture of Christian civilisation, the culture of the family, the moral teachings of the Church, the practice of prayer, participation in pilgrimages and parish processions, pro-life activism, friendship gatherings, and so forth, are all seen as an integrated whole. These are simply understood as the Christian life. Of course, traditional Catholic families go through great difficulties and trials: their unwillingness to compromise with aggressive secular culture and their openness to life (often overlapping with reservations about popular Catholic attitudes towards ‘natural family planning’) entail that such families often undergo serious economic hardships. This can cause suffering for both the spouses and the children, suffering nonetheless accepted as part of life in a vale of tears.

Traditional Catholics reap great rewards for their sacrifices. They can walk around the old towns of European cities and feel that what they see is theirs. They can read churches, go into art galleries, or attend music recitals at concert halls and see these as part of a living material culture that belongs to them, rather than something belonging to a people now dead and gone. Traditional Catholics live an integrated life in which different aspects are interwoven and illumine each other. They understand the Christendom in whose shadow they now live, rather than stumbling about confusedly. Since the healing work of grace is the integration of fragmented fallen human nature, the integrated character of traditional Catholic life suggests that the work of grace is really operating powerfully in the traditional Catholic movement. For the traditional Catholic, catechesis is just one mode by which the integration of the human person takes place, albeit the most explicitly didactic, but nonetheless only one mode alongside other aspects of a lived Catholic life.

After nearly seven years of training people for Church ministry, it is clear to me that contemporary mainstream catechesis is not working. That is, such catechesis is not obtaining its end: the formation of Catholics who in turn know and live the Catholic Faith. Mainstream catechesis is not working, in my view, because generally such catechetical instruction presupposes an anthropology which cannot be accommodated by the Catholic Faith. We cannot speak of the supernatural dignity of man before we have spoken of his fall from grace. Only when we grasp the sinfulness of man can we understand his need for salvation, and consequently the extraordinary dignity to which he has been transformed in baptism.

The optimistic anthropology held by many contemporary Catholics cannot be inferred either from a reading of Scripture or from lived experience. This anthropology makes no distinction between redeemed and unredeemed man, for all are said to be children of God. This anthropology is at the centre of modern catechesis, and in turn the Christian religion is felt to be a mere celebration of our inherent dignity, and thus at root disposable. As the Catholic grows up, he begins to feel that his Catholic catechism classes may have been helpful early in life, but the practices themselves must ultimately be abandoned for the sake of true maturity, especially as the Church has turned out—in his mind—to be so deeply mistaken on all sorts of moral issues.

Even if it were detected by a well-meaning catechist that the Gospels do not affirm the widespread anthropology, the ecclesiastical newspeak which has become the vernacular of contemporary Catholicism has made it nearly impossible to convey the true religion. The fragmentation of contemporary Catholic life is, in turn, giving rise to a fragmented people who understandably choose to leave the Church. After all, at least the surrounding secular culture attempts to offer a coherent picture of human life, albeit based on the primacy of appetite.

Traditional Catholics firmly believe in original sin and can make little sense of the prevailing anthropology in the Church today. Also, not only do traditional Catholics not use ecclesiastical newspeak, but they tend to detect it immediately and they hate it. Raised on traditional catechisms and formed by traditional devotions, they know that the fake jargon of the contemporary Church does not contain the terms with which the Faith is properly expressed. Their love of Latin, even if their knowledge of it is (like mine) quite poor, protects them further from entering into the corrupt idiom of ecclesiastic newspeak. They do not like newspeak and they do not know how to speak it.

The integration of catechesis as just one aspect of an integrated and devotional Catholic life means that for a traditional Catholic it is impossible to apostatise without losing one’s very sense of identity. For some years I, and others I know, attempted to integrate aspects of traditional Catholic teaching and culture into the catechetical approaches of ‘mainstream’ Catholic communities, with varying success. The degree to which this was accomplished was the degree to which the Faith thrived. This experience caused me to conclude that the traditional Catholic movement works. I hope I see the day when the qualification ‘traditional’ is dropped, which is necessitated by the present circumstances, and Catholics can call traditional Catholicism what it is: Catholicism.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity