Especially in the 21st century, we human beings seem to toggle between two extremes in the way we see ourselves: We think we are great, or we think we are worthless. We deny our sin, or we define ourselves by it.

The readings for the Fifth Sunday in Ordinary Time Year C, present us three object lessons that tell us who we really are, and who God is.

First, Jesus climbs into Simon Peter’s boat, invading his work life. He does the same thing to us.

The Gospel begins with Jesus standing by the Lake of Gennesaret — another name for the Sea of Galilee — as a crowd presses in on him, eager to hear what he has to say. Jesus sees two fishermen cleaning their nets and uses their boat as a stage to create some distance between speaker and crowd.

The scene is filled with meaning for the Church — but it is also a clear object lesson to us about what happens in our own lives.

Simon Peter, with James and John, is literally “minding his own business” when Jesus violates his personal space and commandeers his work for his own purposes.

This is exactly what he does with us. We want to live our lives, especially at work, by parameters we set, pursuing our own ends. Jesus can do his thing; we have no objections to him preaching off in his own space in our world. But his own space is over there, not here where I am.

But then, suddenly, something comes up that concerns him and he is standing in our workspace, looking over our shoulder, and we can no longer ignore him.

Simon Peter’s reaction is a model for us.

First, Simon lets Jesus use his boat as a place to preach from. Then, he lets Jesus direct his work. “Put out into the deep and lower your nets for a catch,” Jesus tells him, as if to say, “Go deeper in your faith, and act on it.”

Simon’s personal experience tells him this won’t work. He obeys anyway. “Master, we have worked hard all night and have caught nothing, but at your command I will lower the nets.” The result is more human success than he ever could have imagined as he catches so many fish that they overwhelm his boat and another one.

This is a phenomenon St. Thérèse of Lisieux noticed: Sometimes our first acts of faith produce greater wonders than our mature faith. “For a soul whose faith equals but a tiny grain of mustard seed, he works miracles, in order that this faith which is so weak may be fortified, yet for his intimate friends, for his Mother, he did not work miracles until he had put their faith to the test,” she said.

Then Simon Peter does something important: He tells Jesus how he sees himself.

He sees the miracle the Lord has wrought in his life and says, “Depart from me, Lord, for I am a sinful man.”

There is something good about this humble self-assessment, but there is also something dangerous about it. He is indeed a sinner, but when he defines himself by his sin, he is defining himself exactly the way Satan defines him. Worse, he is defining God the way Satan defines God: As an enemy who rejects sinners and wants to be as far from them as possible, not a savior who loves sinners and draws close to them.

This is how we see ourselves too: When we sin, we are like Adam hiding in the garden, naked and afraid of the Father, convinced that we are not a creature of God but an ugly, shameful thing, and that God is not a savior to be sought, but an angry tyrant to be avoided.

Instead, Jesus says “Do not be afraid; from now on you will be catching men.” He sees not the sinful Simon, but the potential Peter, the rock he is meant to be.

This is exactly what happened to Saul, who became Paul.

In the Second Reading, St. Paul says “I am the least of the apostles, not fit to be called an apostle, because I persecuted the church of God.”

Paul is well aware that he is a sinner. He knows that, on his own, he would be an enemy of Christ. But he also knows that he is not on his own. He has met Jesus Christ, crucified and risen. Now he is defined by God’s love — and wants to tell us that we are also.

“I am reminding you, brothers and sisters, of the gospel I preached to you,” he says. We are neither sinner nor saved; but “Through it you are being saved …. [because] Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures,” he writes.

Now, “by the grace of God I am what I am, and his grace to me has not been ineffective.”

We need to learn the same thing about ourselves. We know how our sins came to define us: Sins against us and by us in childhood created the ache in us that we tried to satisfy with the sins of our teen years. The sins of our teen years opened wounds that led to the pain, anxiety, and addictions of our adulthood.

But Jesus took each of those sins onto himself on the cross. He took the wounds of sin that make us cringe in shame and turned them into his own wounds that heal. Now we are defined not by the sins that crucified him, but by the one who was crucified for our sins.

And that brings us to a last object lesson: Isaiah and the burning coal.

In the First Reading we get to witness Isaiah playing out this whole drama in his own story.

At the beginning of his prophetic ministry, Isaiah sees an image of Jesus Christ — the Lord seated on a throne surrounded by angels, looking just like Jesus will describe himself — and Isaiah considers himself unworthy of being the Lord’s presence.

Then an angel flies to him, holding an ember that he has “taken with tongs from the altar.” He touches it to Jeremiah’s lips, saying, “your wickedness is removed, your sin purged.” Then, when the Lord says, “Whom shall I send?” Isaiah says “Here I am. Send me!”

What is going on here? There is a clue in the first line of the reading: “In the year King Uzziah died …”

King Uzziah was a cousin of Isaiah’s and a good king who did much for the Jewish people. But toward the end of his life he made that other error we make: He began to think he was great in God’s eyes. In fact, he burned incense in the Temple, usurping the role of the priest. Like the angel, he took the coal with tongs and worshiped God, only without fear of the Lord, without the awe and humility he should have.

By taking the coal with the tongs, the angel is taking the shame of the king and literally sticking it in Isaiah’s face. It then becomes an object, not of shame, but of healing.

God does this again and again. When the Hebrews are sinning in the desert on the way to the promised land, they are attacked by snakes — and only when they look upon a bronze serpent, an image of the sin of Adam and Eve, are they healed. It’s the same with Peter after the resurrection: Jesus re-enacts the scene we heard in today’s Gospel, and also re-enacts his three denials, reminding him of his shame in order to save him.

He does the same with our sins at every Mass.

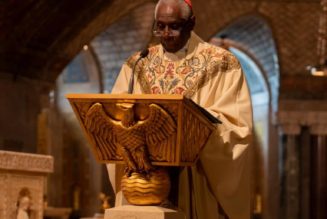

At Mass this Sunday, we are just like Isaiah, staring at God, surrounded by angels. As Sunday’s Psalm describes it: “In the presence of the angels I will sing your praise; I will worship at your holy temple.” As the Catechism describes it: “In her liturgy, the Church joins with the angels to adore the thrice-holy God.”

And what happens in front of us? There at the altar is a crucifix, an image of what our sin did to Jesus Christ, and what Jesus Christ did for our sin. The priest takes bread in Christ’s place and breaks it, saying, “This is my body given up for you.”

We see re-enacted mystically in the liturgy Christ dying for our sins, the act that turned Saul into Paul. Then we come forward and, like Isaiah, have God, the all-consuming fire, placed on our lips. We see and receive the very one to whom Simon said, “Depart from me, Lord, for I am a sinful man.”

We take the body of Christ, wounded by our sin, into our mouth and are restored into the body of Christ, triumphant over sin.

For Peter, this turned the boat of his labor into the boat of the Christ’s grace, the Church. For us, it takes our tiny lives and makes them vessels for the enormous grace God has in store for the world.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity