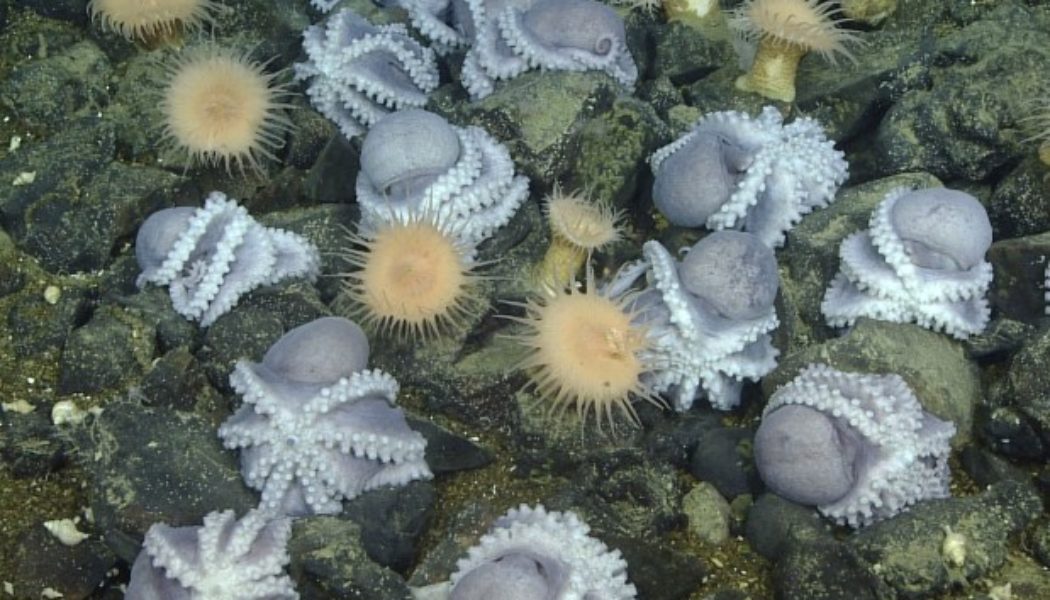

Five years ago, a group of scientists stumbled upon 20,000 pearl octopuses brooding their eggs near the base of an extinct volcano, 80 miles off of the Monterey coast.

They had discovered the largest known “Octopus Garden” on the planet. But for years a question eluded Jim Barry and his team at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute: “What the heck are they doing there?”

The scientists have their answer: Warmer water helped their eggs hatch faster.

The octopuses, lined up like a string of shiny beads, are planting themselves in the crevices of a hydrothermal spring, where warmer water reduces the time they spend incubating their eggs, from five to eight years in colder water to two years or less.

“There are clear advantages of basically sitting in this natural hot tub,” said Janet Voight, an octopus biologist at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago and co-author of an octopus study, published Wednesday in Science Advances.

For three years, scientists monitored the site to understand the hatching cycle, recording both the developmental stage of eggs at 31 nests and the inevitable deaths of octopus moms.

“Usually, colder water slows down metabolism and embryonic development and extends life span in the deep sea. But here in this spot, warmth appears to speed things up,” said Adi Khen, a marine biologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, who was not involved in the study.

Barry, a marine ecologist, was the lead author of the study.

“In order to get this done, so to speak, we needed lots of (different) types of people,” said Barry, meaning everyone from geologists and engineers to biologists and taxonomists. The team also used different types of high-tech tools to make their research possible, including a time-lapse camera that, for a little over five months, took a picture of the octopuses every 15 minutes.

“What we saw from that is that they never leave their nest,” said Barry.

The brooding mothers, about the size of a grapefruit, position themselves upside down and stay there until their babies are hatched. If other animals approach them, such as scavenging shrimp and predatory snails looking to eat one of the babies, they will swat them away.

At 10,500 feet deep, where these pearl octopuses are generally residing, the surrounding water temperature is 35 degrees Fahrenheit. For the octopuses, that means they’re experiencing a temperature similar to a “frosty morning where there’s frost forming on the grass outside,” said Amanda Kahn, an invertebrate biologist at San Jose State, who was part of the discovery team.

But when the mother octopuses sit atop the warm springs, they’re experiencing “still a cool morning, but not with that bite of air,” with temperatures reaching around 41 degrees Fahrenheit.

Kahn was part of the initial team in 2018 that accidentally discovered what researchers dubbed the Octopus Garden. As she puts it, she was “in the right place at the right time.”

She was helping out a research team identify sponges on the underwater volcano known as Davidson Seamount. As she was finishing up one of her shifts, she saw an octopus sitting in a “funny” posture and decided to place the crew’s remotely operated vehicle next to it. Kahn didn’t think much of it at first, but when the crew’s vehicle rose from behind a rock, the lights illuminated thousands of octopuses, revealing one of Kahn’s research subjects for the next several years.

“It was one of those moments where the whole ship made a collective gasp as we realized the importance of what we were seeing,” said Kahn. “Even this sponge biologist recognized something really important was going on here.”

As part of the team that revisited the octopuses, Kahn felt comforted seeing them again, waiting patiently to hatch their young. There was one octopus that Kahn remembers in particular, whom she thought looked like the moon.

“It never stopped being exciting,” Khan said. “Like every time we would go, we would just learn something new.”

The Associated Press contributed to this report.