“With all the unavoidable news right now about disease and epidemics,” Philip wrote here last Friday, “it’s an obvious temptation to look back to past eras to see how they coped with such things, culturally as well as medically.” Indeed, as I get more and more emails from my employer, our kids’ school, and our city about coronavirus/COVID-19, I’ve certainly been tempted to brush up on my limited knowledge of the history of disease. Like Philip, I’ve thought a lot about 1918, and the influenza pandemic that killed 50 million people around the world, including 675,000 in this country. But while he considered how the pandemic — coinciding with the last year of World War I — inspired apocalyptic themes in film and literature, I spent some time this weekend revisiting one of my favorite digital history projects.

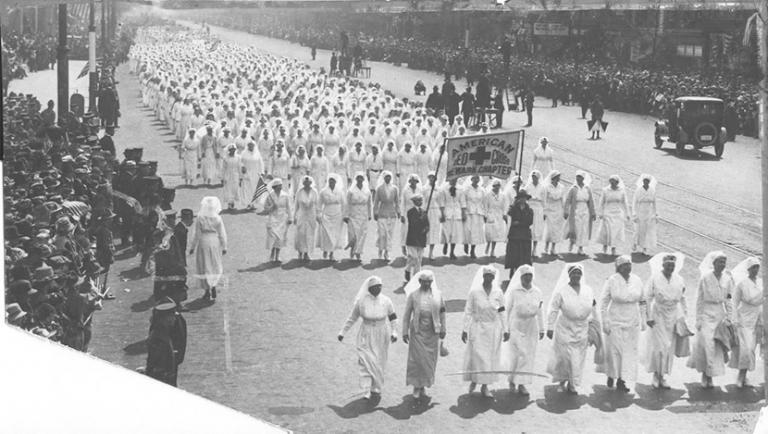

Almost fifteen years ago, the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan began to work on The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919: A Digital Encyclopedia. Updated in 2016, it surveyed how fifty American cities experienced and responded to the “Spanish flu.” The authors wrote a narrative essay and timeline for each city, but even more valuably, they digitized thousands of documents and images. I first used the influenza encyclopedia to research an essay for one of my own digital projects, a 2015 history of Bethel University’s experience of warfare since 1914.

This time I wondered what the encyclopedia’s digital archive would reveal about religious responses to the influenza pandemic in this country. What caught my eye was a set of newspaper articles and other documents dating from late September 1918 through early November of that year — the first peak in the spread of the disease, when cities around the United States banned worship services, among other public gatherings. (Here in St. Paul, Minnesota, authorities waited until early November 1918 to close schools like Bethel. Then a second outbreak caused an “influenza vacation” in the winter of 1920.)

Rather than write a typical blog post, I’m going to share a variety of news stories from those weeks in late 1918. You’ll find a variety of religious responses to the deadliest epidemic in American history, which coincided with the last days of the Great War and the last debates over the ratification of Prohibition. While most Christians made the best of church closures, many grumbled… and a few went to jail rather than stop worshipping.

Sunday, September 29, 1918

BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS: Monday’s front page of the Globe called it the “quietest Sunday Boston ever saw.” With cars largely off the city’s streets and worship services and other public gatherings called off, Boston’s largest newspaper observed that “there was less for the citizens to do probably than on any Sunday since the old Puritan days.”

Sunday, October 6, 1918

CINCINNATI, OHIO: Defying the health board order prohibiting all public gatherings, Father William Scholl held morning mass as scheduled at St. Joseph German Catholic Church. When a police lieutenant arrived on the scene, the priest “declared he was not interested in the order,” but police kept any further services from proceeding. The Enquirer reported “widespread indignation” against Scholl, with “dignitaries of the Catholic Church joining the protest against the disregard of an order that was issued to safeguard the health of the community.”

Friday, October 11, 1918

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA: The city council issued an ordinance closing all churches, prompting the city’s Christian Scientists to protest that they provide “services for the dissemination of a universal understanding of omnipotent Divine power, reliance upon which effectually aids in destroying the dread of contagion….” Four weeks later, a local appeals court refused to release Harry P. Hitchcock, a Christian Scientist “arrested for attending a public church gathering in violation of the city anti-flu ordinances.” One of five Scientists arrested, Hitchcock had argued that the order was an “unconstitutional… unwarranted exercise of the police power.”

Saturday, October 12, 1918

BUFFALO, NEW YORK: While local churches remained closed in accordance with the mayor’s proclamation, “several congregations, however, have arranged to conduct outdoor services” tomorrow. The Courier listed several open-air masses, and St. Paul’s, the Episcopal Cathedral, planned to worship in Shelton Square with the assistance of its full choir: “The service will consist largely of singing of patriotic hymns, and Gen. Pershing’s message to the churches of America will be read….”

Sunday, October 13, 1918

ALEXANDRIA, LOUISIANA: Dr. W.S. Black, rector of the Episcopal church, was dismayed to walk through town and “find the poolroom in full blast, with an ample supply of patrons, none of whom were overly careful as to the degree of distance from their fellow players.” Black didn’t understand how he could keep his church closed while such establishments remained open. “I believe in obeying the law of the constituted authorities,” he told the New Orleans States, “but I am under pledge to the boys ‘over there’ that at the customary times of service… certain prayers shall be said in which they are specially remembered….”

SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH: “For the first time in many years,” the Deseret News reported the next day, the city’s Mormon tabernacle and about fifty other Latter-day Saint chapels — plus other churches and synagogues — were closed this Sunday. Even funerals were suspended because of health regulations for the epidemic. But “in a few instances pastors assembled groups of young people in front of their churches, and either held service there, or marched to some park or recreation grounds, and enjoyed the autumn sun-shine as well as imparting religious instructions to the assemblage.”

Monday, October 14, 1918

BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA: “We have had the strange experience of a churchless Sabbath,” wrote the Methodist revivalist George R. Stuart in the Age-Herald, “what has it taught us?” Most importantly, the pandemic should convince “Intelligent Christians” to trust science rather than seeking to “tempt God to perform a miracle in the preservation of our health… Christians do not discount their faith in the omnipotence of their God by keeping their bodies and homes and streets clean and nongerm producing; by using care in traffic and travel, accepting vaccination, sprays and disinfectants and keeping God’s own laws of health and life. Any other course is the fruit of ignorance and false teaching.”

Tuesday, October 15, 1918

BALTIMORE, MARYLAND: The city’s leading Catholic clergyman continued to question why local churches were closed “while the stores, saloons, markets and the like remain open.” While recognizing public health concerns, James Cardinal Gibbons argued that “it would be a much-needed relief to our church-going population if they could be allowed to attend brief morning services… I am told that a number of calls upon our physicians are simply the result of nervousness, or the consequence of alarm. This might be considerably allayed by the reassurance of religion, and discreet words from our priests given the people in church.”

Friday, October 18, 1918

WORCESTER, MASSACHUSETTS: The Daily Telegram shared examples of how Christians were responding to influenza, even as public worship ceased. Women from three local churches were taking care of “epidemic orphans,” giving them not only food and clothing, but “[supplying] them with plenty of healthful recreation and a little systematized instruction, too.” And a Catholic women’s club brought clothing and food to influenza patients, including 28 jars of applesauce, 28 quarts of lamb stew, and 35 squares of johnny cake.

Sunday, October 20, 1918

MILWAUKEE, WISCONSIN: The Journal found that church closures didn’t leave the city’s “pastors with any surplus of leisure on their hands.” With the faithful encouraged to engage in “home worship” and read sermons published in newspapers, Protestant and Catholic clergy were instead devoting more of their energy to pastoral care and sick calls.

SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA: At an open air service in front of First Baptist Church, the interim pastor suggested that the churches themselves “are to blame” for the influenza epidemic. Rev. John Quincy Adams Henry preached that Christian churches “have been lamentably weak in moral and spiritual leadership and have not yet risen to the august occasion confronting them. Our churches have become conventional, cowardly and worldly. Not only the people, but the churches must repent their sins, and when they do the plagues will cease.”

INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA: Ten black “Apostolic” Christians were arrested for attempting to worship in defiance of the board of health. “When the [seven] women and [three] men were taken to police headquarters,” reported the News, “they began talking in the ‘unknown tongue’ and it was some time before the turnkey and matron were able to learn their names.”

Tuesday, October 22, 1918

NEWARK, NEW JERSEY: “To avoid the dreaded influenza,” advised the Star-Eagle, “children should play in small groups and outdoors or in well-ventilated rooms.” The paper began to share games suggested by the Young Men’s Christian Association, including “Japanese Tag… In this version of the game… when a player is touched or tagged, he must place his left hand on the spot touched… [and] in that position must chase the other players.”

Saturday, October 26, 1918

GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN: The Herald doubted that anyone has suffered more from the state ban on public worship than the members of the city’s seventeen Christian Reformed churches, who “have been trained from childhood to regard regular church attendance as natural in their lives as eating breakfast.” Families are trying to fill the gap with private worship, but Reformed leaders are upset that churches are closed while schools remain open: “…it would seem that if there were danger of contagion anywhere it would be among the physically undeveloped youngsters congregating in the school rooms day by day.”

Sunday, October 27, 1918

NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA: On the same page that the States printed a sermon by a Methodist pastor for those “who are detained from their houses of worship because of the epidemic of influenza,” it reported on the financial consequences for closed churches unable to collect tithes and offerings: “This loss… ranges from $20,000 to $25,000… the most serious set back the churches have received is the delaying if not absolutely destroying the chance of securing the benevolent money for church work during the Winter.”

Thursday, October 31, 1918

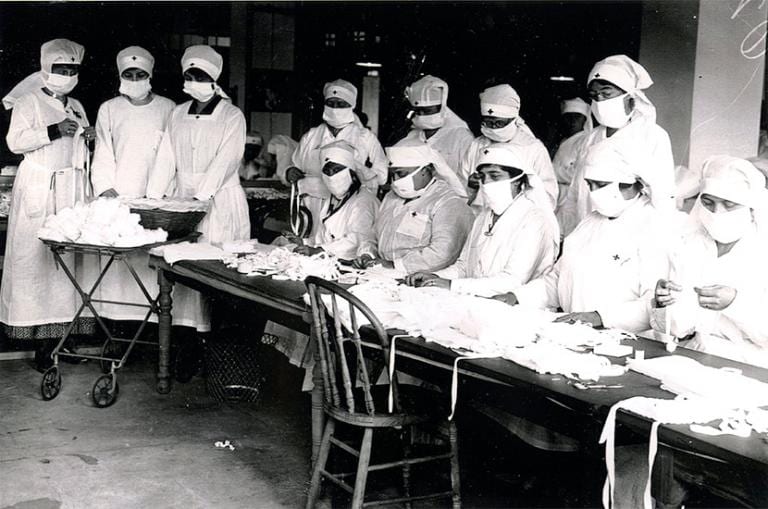

DETROIT, MICHIGAN: The Roman Catholic bishop of Detroit, Michael J. Gallagher, joined businessmen and movie theatre owners in pleading for the statewide ban on public gatherings to be lifted. The News reported that those notables “were willing to have their edifices fumigated between meetings, to cut the services to 45 minutes, to employ special ushers, who would eject persons who coughed or sneezed and to require all worshipers entering a church to wear influenza masks.” But state officials weren’t persuaded, since “Massachusetts and Pennsylvania had found that the exemption of churches tended to nullify the effects of the closing order.”

Friday, November 1, 1918

DALLAS, TEXAS: With special permission from the mayor, Catholic and Episcopal churches planned worship for All Saints’ and All Souls’, with St. Matthew’s Cathedral holding “special services for the boys who have died in France and will have a special requiem celebration of the Holy Communion.”

Saturday, November 2, 1918

ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI: Samuel Thurman, rabbi of the first synagogue established west of the Mississippi, affirmed the closure decision by the chief of the health board: “Due to his determined action, St. Louis has been spared the terrible fate of other cities of its size and larger… The price we are paying now is commensurately small compared with the gain and good we shall obtain in the end. Let us be patient. Let us hope and pray for a speedy banishment of the dread monster, disease, from our midst, and a happy return to the healthy and normal life of the community.”