Steven D. Greydanus

“Her whole life was an attempt to tell her real story. That never really happened. I hope it can posthumously.”

So laments Protestant minister Rob Schenck, a onetime pro-life leader with Operation Rescue and one of three pastors who co-officiated the 2017 funeral of Norma McCorvey, along with his former colleague Flip Benham, who baptized McCorvey in a swimming pool in 1995, and Father Frank Pavone of Priests for Life, who received her into the Catholic Church in 1998.

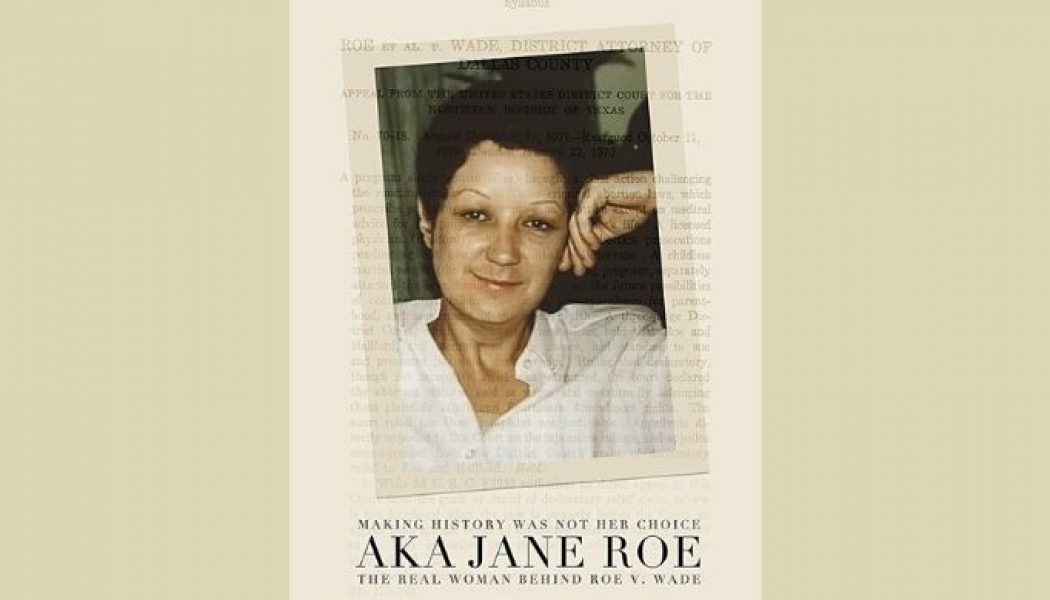

The lament appears almost at the end of Nick Sweeney’s documentary AKA Jane Roe, following heavy-handedly after a clip from McCorvey’s funeral with her daughter Melissa talking about McCorvey participating in this very documentary “to show who she was in the end.”

Sweeney couldn’t be more explicit in claiming the previous 75 minutes or so as, finally, McCorvey’s Real Story.

Part of this Real Story narrative, of course, are all the previous narratives, most of them complicated by other voices and interests.

There’s the original “Jane Roe” story from the 1973 Supreme Court case for which McCorvey was a plaintiff of convenience.

There’s her 1994 pro-choice memoir I Am Roe (written “with Andy Meisler”). Just three years later came her pro-life conversion story Won by Love (written “with Gary Thomas”).

For many years afterward McCorvey told this story over and over at pro-life events. Central to Sweeney’s Real Story narrative is McCorvey’s “deathbed confession” that her years of pro-life advocacy were “all an act. I did it well, too. I am a good actress.”

“Of course,” she adds, “I’m not acting now.”

In the wake of advance press coverage for AKA Jane Roe claiming, misleadingly, that McCorvey was “paid to change her mind” on abortion, prominent Christian pro-life leaders who knew McCorvey have scrambled to try to reclaim her memory, insisting that McCorvey’s conversion and pro-life conviction were sincere, and even that she reaffirmed her stance in the days and hours before her death.

Complicating the “deathbed confession” narrative, AKA Jane Roe acknowledges that McCorvey could be an unreliable narrator of her own life.

Looking back, McCorvey recalls her mother lying to the courts to take custody of her daughter Melissa. However, her friend Charlotte Taft, an abortion-rights activist and counselor, states frankly that framing herself as a victim was easier for McCorvey than acknowledging the issues, including her alcohol and substance-abuse problems, that made her unable to care for Melissa.

Taft and Schenck are the two key voices who help establish what emerges as the thesis of Sweeney’s Real Story narrative: that the pro-choice movement failed McCorvey and the pro-life movement exploited her. The difference between those two verbs is crucial. While AKA Jane Roe acknowledges that McCorvey was poorly treated by both sides of the abortion debate, the critique of pro-choicers is couched in terms of unfortunate missteps, while pro-lifers are condemned for what are cast as essential failings.

Abetting this uneven presentation, the pro-choice perspective is ably presented, with thoughtful self-criticism, by capable advocates like Gloria Allred, McCorvey’s attorney, and Taft, who explains how fellow pro-choice leaders held McCorvey at arm’s length, leaving her feeling unwelcome.

On the pro-life side, Sweeney allows Schenck to speak as a self-critical evangelical pro-lifer for nearly the whole documentary, only explicitly acknowledging in the last 10 minutes or so that he has abandoned his pro-life advocacy and embraced a progressive, pro-choice version of evangelicalism. That leaves the smarmy Benham as the documentary’s sole voice of a pro-life perspective generally presented at its least attractive (gory posters, confrontational tactics, etc.).

None of which is to say that Schenck’s critique is without merit. Far from it.

McCorvey’s journey from pro-choice icon and counselor to pro-life superstar began in 1995, when Benham, then director of Operation Rescue, sat down next to McCorvey on a bench outside the Dallas strip mall where Planned Parenthood and Operation Rescue occupied adjacent suites. Here, at least, Benham’s and McCorvey’s memories converge: As they talked, it seemed that in some ways they weren’t so different.

After her baptism, McCorvey said in an interview that pro-lifers had “shown me what it’s like to be a human being for the very first time in my whole life. They’ve loved me, they’ve nurtured me, and they’ve cared for me.”

Connie Gonzalez, a fellow Planned Parenthood employee and McCorvey’s longtime lover until her conversion, has a different perspective: She says Benham was a charming phony who was nice to people he wanted to win over.

However genuine or phony Benham’s manner, two things are clear: First, the only reason he and McCorvey were sitting on that bench was that he had deliberately moved Operation Rescue into the suite next door to the Planned Parenthood where McCorvey worked, a move typical of the controversial organization’s aggressive style.

Second, Benham immediately began using McCorvey to promote the cause. This is obvious even in his denials; when a reporter presses him, “Would you care just as much about anybody else as you do about McCorvey?” his revealing response is: “God has given Norma to us.”

Notably, neither McCorvey nor anyone interviewed in AKA Jane Roe denies the genuineness of her conversion experience or her faith. What emerges, not implausibly, is that her new life involved a number of distinct elements about which she had complicated feelings.

On the one hand, Taft has acknowledged — though, significantly, the documentary does not — that McCorvey had long harbored conflicted feelings about abortion and her pro-choice activism. In place of long-simmering doubts and guilt, she now had forgiveness and redemption as well as love and a sense of belonging.

As a celebrity convert, perhaps McCorvey also enjoyed a renewed sense of importance, of recognition she felt had been denied by pro-choice leaders, especially at first.

On the other hand, there was her sexual relationship with Gonzalez, which, according to both her and Gonzalez, came to an end after her conversion, though they continued living together.

According to Schenck, McCorvey’s new pro-life convictions were at least wobbly regarding first-trimester abortions. Certainly she was coached and given talking points — from both sides of the abortion debate — and, if her advocacy in both cases came with financial incentives, that would hardly have been her sole motive.

Later on, McCorvey seems to have increasingly felt exploited and focused on getting what was coming to her. Her assessment that “it was a mutual thing,” that she and the pro-life movement each used the other, seems reasonable.

Hard questions for both sides remain unanswered. Schenck regrets that McCorvey’s funeral was turned into one more pro-life rally; if McCorvey’s pro-life stance was all an act for money, and she had nothing but contempt for gospel preachers, why were Benham and Father Pavone at her funeral at all? (McCorvey’s daughter was part of the end of her life and of the documentary; it’s reasonable to suppose that the funeral reflected McCorvey’s wishes.) On the other hand, if the pro-life leaders now claiming how well they knew McCorvey were so close to her, why did her “deathbed confession” come as such a shock? Where were they in her needy last years?

What, finally, defines McCorvey’s life? What is the essence of her real story? Even she might not have fully known in the end. AKA Jane Roe highlights some of the difficulties of arriving at the truth, but it’s ultimately one more spin on McCorvey’s life, highlighting the ambiguities and tensions on one side of the coin and downplaying or ignoring those on the other.

Deacon Steven D. Greydanus is the Register’s film critic and creator of Decent Films

He is a permanent deacon in the Archdiocese of Newark, New Jersey.

Caveat Spectator: A brief shot of an explicit, gory anti-abortion poster; mature content, including references to rape and sexual abuse; profanity and crude language. Mature viewing.