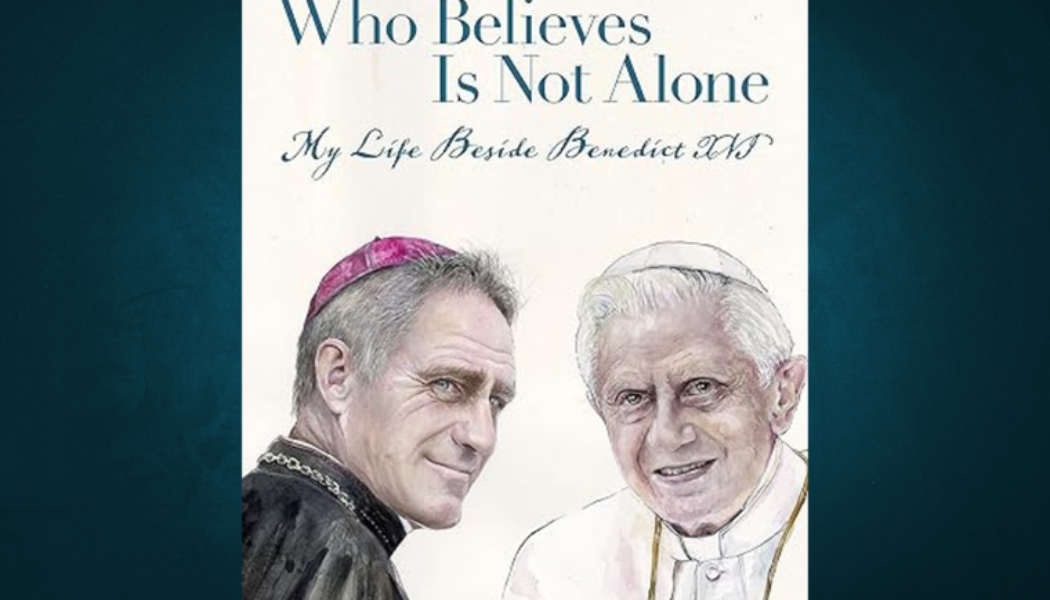

Who Believes Is Not Alone

My Life Beside Benedict XVI

By Georg Gänswein

With Saverio Gaeta

St. Augustine’s Press, 2023

274 pages, $24

To order: staugustine.net

Joseph Ratzinger/Pope Benedict XVI lived a fascinating and exceptional life. Millions of faithful Catholics not only have a desire to honestly know Joseph Ratzinger better, but have legitimate wonders surrounding the events of his final decades, some of which have been largely veiled until now — until this book by Archbishop Georg Gänswein.

(The book was first published earlier this year in Italian under the somewhat more provocative main title Nient’altro che la Verità [Nothing But the Truth], but St. Augustine’s Press has translated it to English with a new title.)

In early 2003, Cardinal Ratzinger asked Msgr. Georg Gänswein to be his personal secretary. What was intended to be a temporary assignment turned out to be a 20-year position, as Gänswein faithfully served Joseph Ratzinger from 2003, through his papacy, and through his retirement until his final moment on earth on the last day of 2022.

As co-author Saverio Gaeta writes in the book’s postscript, “No one knew and supported Benedict XVI throughout the years of his pontificate and retirement more than Archbishop Georg Gänswein.”

Even beyond that singular honor, Archbishop Gänswein has been a firsthand witness of Vatican operations for 20 years. As Archbishop Gänswein writes, “The weighty responsibility of serving as his personal secretary, together with my role as prefect of the Pontifical Household during the papacy of Pope Francis, gave me the opportunity to take part in every important ecclesial event over the last two decades.” Thus, Archbishop Gänswein was in a particular position to observe the inner workings of the Vatican for the past two decades over three pontificates.

When news of this book first hit the presses, many expected or hoped (others even worried) this would be a tell-all exposé, but this book is not that. This book is primarily a beautiful glimpse into the life of Pope Benedict and a revealing look at the office of the papacy itself. It is both a biography of Joseph Ratzinger and partial autobiography of Archbishop Gänswein. It has a wonderful tone and excels as the poignant story of a friendship centered in Christ. The author’s loyalty and admiration of Pope Benedict are evidenced throughout the text. Thus, readers of this book should appreciate that.

All that said, Archbishop Gänswein does reference some of the most tumultuous events and disagreements involving the Church hierarchy during the past 20 years.

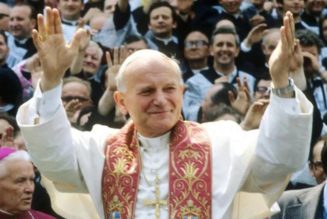

An early section of the book focuses on then-Cardinal Ratzinger’s time as head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and of his friendship with Pope St. John Paul II. Archbishop Gänswein writes, “Pope Wojtyla’s collaborators testify that he never made an important decision without first consulting Cardinal Ratzinger.” That said, they did have disagreements, including the Pope’s attendance at the Assisi conference in 1986. As Archbishop Gänswein writes,

“Cardinal Ratzinger thought it inopportune for him to participate in the gathering. He thought that the unqualified gathering of such a vast range of cultic expressions represented by the sixty-two religious leaders assembled in the city of Saint Francis would cause serious confusion, and he feared his mere presence at the event would suggest that the pope saw no problem with it. Indeed, the program did include some ceremonies in local churches that were simply inappropriate, such as the placement of a statue of Buddha near the tabernacle and a peace pipe upon the altar. Moreover, during the midday prayer service in the main square outside of the lower basilica, the ordering of the prayers — even though there was a pause for silence between them — had an air of syncretism and the ring of relativism.”

Pope John Paul II’s participation in this conference has been widely considered one of the most troubling events in his papacy, so it was edifying to me to discover that Cardinal Ratzinger objected to it.

Archbishop Gänswein goes on to outline Cardinal Ratzinger’s election to the papacy — an election that Cardinal Ratzinger ardently did not want to win. Noting the tremendous responsibility and weight of the papacy, the author observes that “no one — unless he suffers from some deep psychological abnormality — really has any ambition to occupy the Chair of Peter.”

Cardinal Ratzinger had no such ambition. Archbishop Gänswein quotes Cardinal Ratzinger, “With profound conviction I said to the Lord: Do not do this to me! You have younger and better people at your disposal, who can face this great responsibility with greater dynamism and greater strength.” Obviously, the College of Cardinals chose him anyway.

Once in office, Pope Benedict XVI became responsible for more than a billion Catholics, along with addressing numerous serious problems in the Church. This would be a staggering prospect for anyone on earth, but particularly someone with health and fatigue issues. The year following his election, Benedict admitted, “So many things should be done, yet I see that I am not capable of doing them. This is true, I imagine, for many pastors, and it is also true for the Pope, who ought to do so many things! My strength is simply not enough.”

Nevertheless, Benedict faced the Church’s troubles — and the world’s troubles — with strength and grace. Archbishop Gänswein outlines Benedict’s dealing with issues such as clerical sexual abuse, the spread of AIDS, the oppression of the Catholic Church in China, the fallout from the Regensburg address, and many others. He also devotes considerable attention in the book to addressing the details with the “Vatileaks” scandal, in which Benedict felt betrayed from within.

Looking back at the papacy of Pope Benedict XVI, it is unfortunate that his papacy is often remembered foremost by his abdication. It is also unfortunate that his abdication gave rise to confusion and conspiracy theories. Thus, it does a real service to Catholics that Archbishop Gänswein explains in detail how and why Pope Benedict came to his decision:

“The fact is that Ratzinger had had a series of health problems over the years, including a stroke in 1991, which had weakened the vision in his left eye. A couple of falls in 1992 and 2012 led to stitches on his head, and he underwent surgery to repair a fracture in his right wrist in 2009. He needed to have a pacemaker installed in 2003 to regulate an irregular heart rhythm, which was replaced twice (in 2012 and 2022).”

Benedict noted that Pope John Paul II — who also underwent considerable health problems toward the end of his life — had experienced tremendous difficulty performing the required functions of the papacy, and he did not want the Church to suffer as a result. And lest we forget, we are speaking about a man who was in his mid-80s. From a human perspective, what was shocking was not that Benedict chose to retire, but rather that he was able to accomplish as much as he did at his age.

Archbishop Gänswein recounts that, on Sept. 25, 2012, Pope Benedict explained to him, “I have reflected, I have prayed, and I have come to the conclusion that, on account of my diminishing strength, I must renounce the Petrine office.” Though his secretary suggested a lighter schedule for him, Benedict was firm in his decision — and that he was doing God’s will in resigning. Clarifying that abdication is completely allowed by canon law, Archbishop Gänswein’s book provides the text of Benedict’s formal declaration, which was signed and dated:

“After having repeatedly examined my conscience before God, I have come to the certainty that my strengths, due to an advanced age, are no longer suited to an adequate exercise of the Petrine ministry. … For this reason, and well aware of the seriousness of this act, with full freedom I declare that I renounce the ministry of Bishop of Rome, Successor of Saint Peter.”

The book includes a detailed account of Pope Benedict’s last days in office, followed by a fascinating section on his last years and last days on earth. Within this section is a chapter detailing the relationship between Pope Francis and the pope emeritus as well as the relationship among Archbishop Gänswein, Benedict and Pope Francis — which was not without hiccups. The author writes that Benedict was aware that Catholics seemed to be taking sides, but the “habit of people taking one side or the other and placing the reigning and retired pontiffs at loggerheads was something that terribly upset Benedict.”

I will admit that when I saw the title for Chapter 8, “The Relationship Between Francis and Benedict,” I was tempted to skip ahead to that chapter, but I read from the beginning, which certainly helped me make sense of everything that followed. But to reiterate, this is not the most interesting part of the book to me. Rather, the book excels primarily as a biography — or at least as a biographical glimpse in time of one of the greatest theologians of our age.

I am pleased that Archbishop Gänswein devotes much time to highlighting the theology of Benedict — especially as addressed in his encyclicals and in his trilogy on the life of Jesus. Hopefully, this new book will spark many Catholics to read or reread the brilliant writing of Joseph Ratzinger.