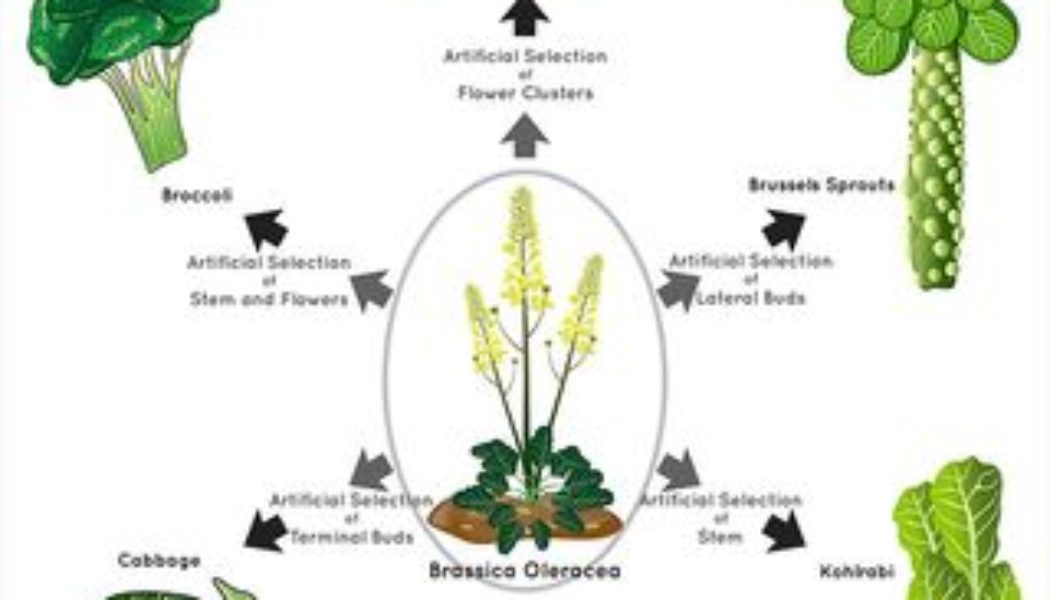

Kale, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, collard greens and kohlrabi have unique nutritional values, and we think of them as distinct vegetables. Yet, they all share the same species name. Could they all really come from the same plant?

The short answer is yes, and humans are responsible for the differences among these veggies.

“It is all one plant, Brassica oleracea, that humans have selected over multiple generations to have these varying vegetables that we all enjoy eating,” Makenzie Mabry, an evolutionary biologist at the Florida Museum of Natural History, told Live Science.

Chris Pires, an evolutionary biologist who studies crop science at Colorado State University, calls these veggies “the dogs of the plant world.” All pet dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) are the same species, domesticated from wolves (Canis lupus), and they come in different varieties, or breeds. Similarly, broccoli, cauliflower, kale and the other aforementioned vegetables were also domesticated from the same species, B. oleracea.

Related: Where did watermelons come from?

Of course, many crops were cultivated for specific traits too, such as heirloom tomatoes. But unlike those crops, which are bred for different colors, tastes and sizes, Brassica varieties are bred from the plant’s different physical parts.

“We domesticated all of the plant parts,” Pires noted. “The stem, the inflorescence [flower cluster], the leaf, the underground parts.”

That domestication resulted in a wide range of nutritional diversity, too. As each variety adapted to different environments, it produced different amounts of antioxidants and bitter compounds, Alex McAlvay, an ethnobotanist at the New York Botanical Garden, told Live Science. Even the same vegetable can have different nutritional values depending on whether, and how, it’s cooked. For example, “people have bred Brussels sprouts to be creamier, less bitter, more flavorful,” Pires said.

And each veggie has had its bout of fame. In the U.S., kale only became popular for its so-called superfood properties in the past few decades, and in early 2024, The New York Times published a story about cabbage “having a moment.”

Even beyond the seven main vegetables produced from B. oleracea, there are two to three dozen varieties that are specific to various regions of the world because different groups of people domesticated those plants locally. In the American South, for example, collards were brought over by European colonists and eventually became a staple of Southern cuisine. And the plant continues to develop in modern research labs; Broccolini, a cross between broccoli and Chinese broccoli (also known as Chinese kale), was introduced in 1993.

Scientists are still deciphering how and why humans artificially selected certain traits from different parts of B. oleracea. Those origins date back thousands of years, when our ancestors cultivated different parts of the plant — in some cases, by accident.

“They were weeds before they were crops,” McAlvay said. As some societies cultivated the weeds with less-bitter leaves or more tender shoots, for example, those traits evolved into the crops farmers now grow commercially.

One reason it’s difficult to trace that ancestry is because the climate and environment 2,000 years ago were vastly different than they are today, Pires noted. He and Mabry worked on a study in which they attempted to trace those lineages. They found evidence that Brassica cretica, a flowering Mediterranean plant, is the closest living relative of B. oleracea. Despite their progress, the picture remains incomplete.

“How do you figure out the origins of something where you don’t even know what the ancestor looks like?” Pires said.

Our current understanding of the Brassica family tree would crumble in an instant if another ancestral variety were discovered, for example, or if archaeologists sequenced the ancient DNA of a fossilized relative, Pires said. Our evolutionary understanding of the species is constantly changing.

Another reason for the mystery is the way crops evolve. Once humans cultivate plants, they can later become feral if abandoned, Mabry said. Crops can also turn feral if they hybridize with nearby wild varieties through cross-pollination. Wild plants, by contrast, have never been cultivated. In this sense, B. oleracea has become an important research model for scientists’ understanding of hybridization and larger evolutionary processes.

The coolest thing about this plant? “Everyone grows these in their backyard,” Mabry said, noting that it’s a go-to beginner crop for home gardeners. “I think we have a real close connection to this plant as a society.”