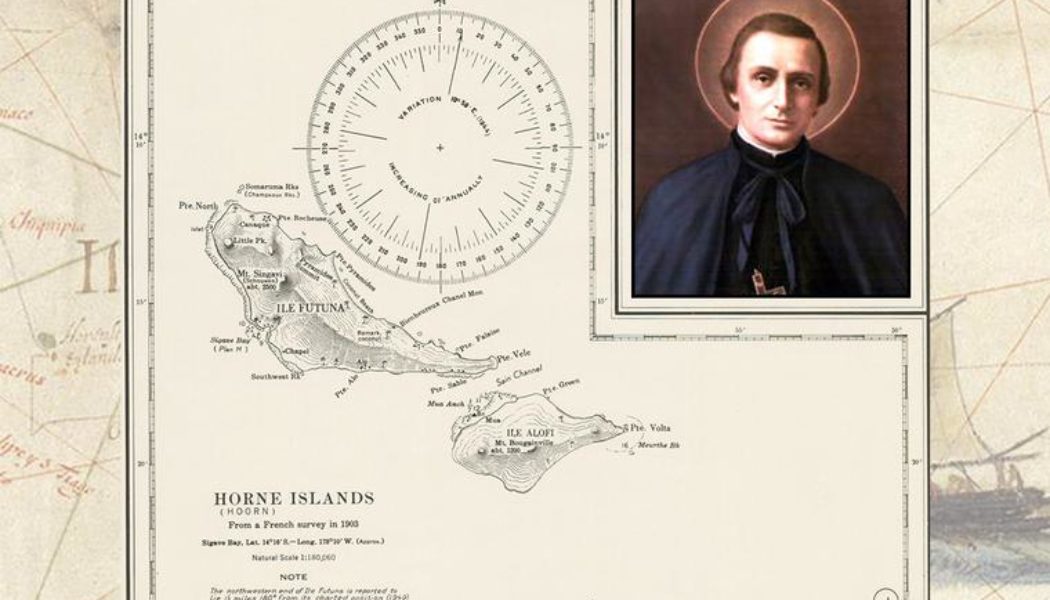

Ever hear of a place called Futuna? If not, don’t be surprised — you probably haven’t unless you are a philatelist. While it’s not exactly the “remotest place on earth” (Tristan da Cunha, in the South Atlantic, claims that distinction) you probably aren’t going to wind up on Futuna unless you really want to. It’s about 3,100 miles east of Australia and 1,800 miles northeast of New Zealand in the South Pacific. By those stretches, “nearby” American Samoa — a little over 500 miles east — is practically a leisurely swim away.

How about someplace called Cuet? Probably not heard of that one, either. While France isn’t as remote as the South Pacific, there are small towns in that country not exactly a hop, skip or jump away from big cities. Cuet lies in eastern France, about 40 miles north of Lyons or 80 miles west of Geneva, Switzerland.

Towns off beaten tracks don’t garner much attention. In Polish, we even have a saying for such places: tam gdzie nawet Diabeł mówi ‘dobranoc’ (“where even the Devil says ‘good night’”). In English, we call them “God-forsaken.”

Neither one of those things is, however, true. First, St. Peter the Apostle reminds us not to be sleepy because Satan does not sleep but “prowls like a roaring lion, seeking someone to devour” (5:8). And no place, certainly in this world is God-forsaken — for proof, see Psalm 139.

God seems to like to write salvation history in places like Futuna and Cuet and Bethlehem and Nazareth, the last a town of which has been asked whether “anything good can come from” it (John 1:46). Scripture tells us of far greater things happened in one-donkey Jewish towns like Bethany and Nain, Capernaum and Cana, than in Washington or Moscow, London or Beijing.

So, what about Cuet and Futuna?

Cuet was near where he was born, and Futuna was where he was born to heaven. Who? St. Peter-Louis-Marie Chanel, whose feast we celebrate April 28.

Peter Chanel was born near Cuet in 1803, one of several children. As a child, he worked as a shepherd when a local priest noticed his intelligence and got him into school. Another priest noticed his piety and steered him toward the seminary. The shepherd boy progressed rapidly, taking class prizes in Latin and speech. Minor and major seminary followed, and Chanel was ordained July 15, 1827.

He spent some time as a vicar in Ambérieu-en-Bugey (another town in eastern France). Even before finishing seminary, however, he had seen correspondence with the local Bishop of Bellay from foreign missionaries and felt attracted to be one himself. He applied to the bishop, who refused his request, assigning him instead to a poor church in Crozet, near the Swiss border, where he spent three years and renewed a neglected parish.

In 1831, Chanel joined the Society of Mary, the Marists, who undertook domestic and foreign missionary work. God’s plans move in mysterious ways and, instead of getting a missionary assignment, Chanel was assigned as spiritual director to the Bellay diocesan seminary, a post he held five years. The Marists were only beginning to be established as a religious order, and the Pope eventually entrusted them with responsibility for organizing the local church in western Oceania. Their initial remit covered a swath as wide as New Zealand, Tonga, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, New Caledonia, Samoa, and … Wallis and Futuna, two islands that came under French protection.

Seven Marists set sail for their tropic island nest on Christmas Eve, 1836 from Le Havre, France. It was no “three-hour tour.” After circumnavigating the Americas, Chanel arrived in Futuna Nov. 8, 1837, almost 11 months later. He celebrated his first Mass on the island on the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception, Dec. 8, 1837.

King Niuliki initially welcomed Chanel. His efforts to implant the faith at first yielded meager results but, with zeal and perseverance (as in Crozet), Chanel began slowly to turn things around. Eventually, the number of catechumens began to grow to include Niuliki’s son and daughter. Enraged at departure from tribal religions and feeling his own status endangered, he sent warriors to ransack Chanel’s village. They injured many catechumens and murdered Chanel on April 28, 1841, shattering his arm, bayoneting him and clubbing him to death. Eventually, they split his skull open with an adze, a tool resembling a hammer used to shape wood. Buried locally, his remains were eventually taken back to France, his beatification proclaimed in 1889, his canonization in 1954. Today, most of Futuna is Catholic.

How is Chanel relevant to us today? Some thoughts:

- Chanel shows us that sanctity originates everywhere and can be lived everywhere and at every stage of life. He died just short of 38.

- Chanel shows us the importance of the missionary life. The Church must always be missionary: that was the mandate she received from the Lord just before his Ascension (Matthew 28:20), a solemnity often falling near Chanel’s feast day. Once upon a time, giving one’s life to the missions as religious was something young men and women aspired to. Chanel’s part of the world would produce another martyr missionary: Blessed Maurice Tornay (1910-1949), shot by Tibetan lamas.

- Chanel has not yet been tarred by woke ideologies that attack Christian missionary work as undermining respect for “local culture” or as vehicles for European colonialism. Chanel’s brutal murder — like that of the North American Martyrs in the 17th century — refutes today’s mythology of “peaceful” indigenous peoples and cultures as much as it does Rousseau’s of the “noble savage.”

- In the history of the Church, Chanel is relatively modern. Our interconnected global world might forget that, less than two hundred years ago, the islands of the western Pacific were almost terra incognita.

In terms of “art” connected with St. Peter Chanel, let’s just say one of the down sides of being “relatively modern” is that there is relatively little serious art that has been devoted to the Protomartyr of Oceania. I cannot even identify the provenance or medium of today’s illustration — it may be a poster or painting somewhere in some church. Maybe that’s appropriate for our off-the-beaten-path saint. I selected it because it encapsulates St. Peter Chanel in three ways:

- It gives us a sense of whom St. Peter Chanel was. He was a zealous priest in his late 30s, evident by his youthful face, his optimism (slight smile) his right hand raised in blessing, and his cassock.

- It links him geographically to his beloved South Pacific. He holds a palm, which does double duty (as the palm of a martyr’s victory and as indicator of the flora of the region). The background also does double duty: it is off-gold (compared to his halo), alluding not just to the “shining sea” but also showing some affinity to iconic representation where a saint is usually set against a celestial gold background of heaven. In the upper left is his place of martyrdom: the island of Futuna.

- It attests to his devotion to Our Lady, with his motto “aimer Marie et le faire aimer” (to love Mary and to make her loved) in the upper right, under her image, gazing at another son about to die doing God’s will. It is a fitting motto for an original member of the Marists.

In terms of geography, Chanel took many roads “less traveled by” but, as Robert Frost observed: “And that has made all the difference” — on earth and in heaven.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity