While strolling through the streets of Turin, Friedrich Nietzsche once spotted a horse being whipped. Inwardly moved, he flung his arms about the animal’s neck and wept bitterly.

It was Jan. 3, 1889. The rest of the month, he who once proclaimed the death of God sent postcards to friends and world leaders, signing them either as “Dionysus” or as “The Crucified,” and announcing through them the fulfillment of the kingdom of God in his own person. Both to the king of Italy and the Vatican secretary of state, he affirmed his intention to come to Rome and meet the pope. Before long, however, he had a complete medical collapse, lost lucidity and descended into silence. He spent the last decade of his life out of the public eye, first constrained to an asylum and then in the care of his mother and his sister.

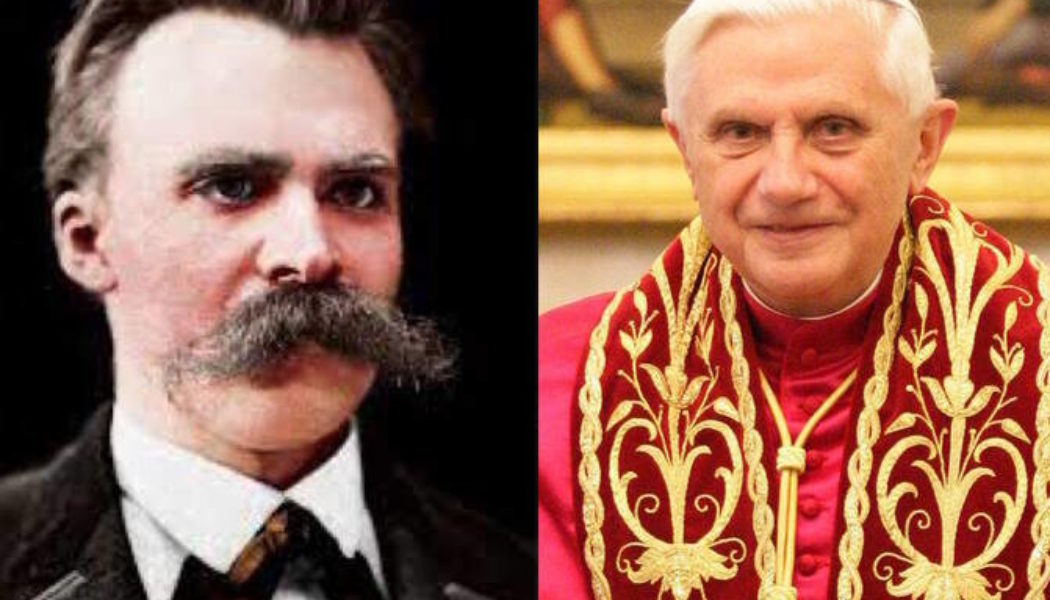

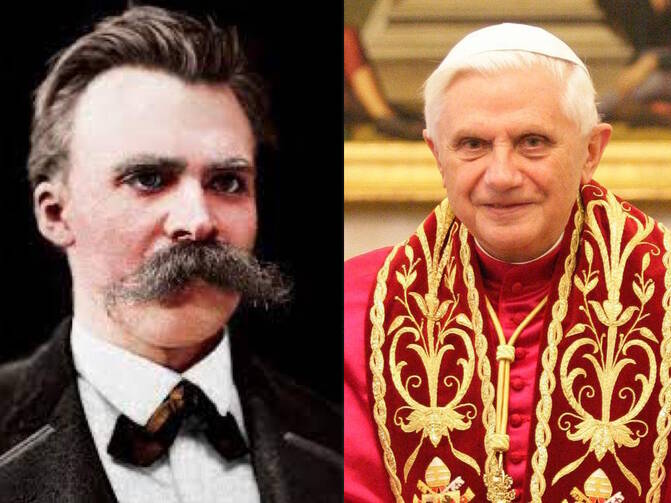

Benedict finds in Nietzsche a privileged interlocutor, and the ensuing dialogue affords him the welcome opportunity to formulate clear and compelling answers to the crucial questions of our times.

Three years before voluntarily entering into his own 10-year retirement, Pope Benedict XVI visited the Shroud of Turin and recalled Nietzsche’s witness to the death of God. That proclamation, he underscored, belongs to the original Christian understanding of Holy Saturday and has become even more poignant for us after a century of gulags and genocides. Yet Benedict reminds us that, just as the Shroud is a kind of photographic negative of the crucified Christ, so the death of God is the negative of Christ’s resurrection. We who dwell increasingly in the spiritual landscape of Holy Saturday may yet hope for the joy of Easter morning.

One of the more remarkable things in a pontificate full of surprises is the fact that Benedict’s major writings involved a significant engagement with the thought of Friedrich Nietzsche. The late pope’s justly celebrated first encyclical, “Deus Caritas Est,” and his best-seller Jesus of Nazareth confront Nietzsche’s antithetical claims regarding the Christian way of life.

Needless to say, Nietzsche is an unlikely conversation partner for a supreme pontiff because he, more than most, realized fully the yawning abyss in the human spirit that opens when God is no longer the center of our existence, an abyss that someone or something must fill. For Nietzsche, only the few—those philosophers well favored by nature and by culture—are potent enough to insert themselves in that space and experience joy.

Such a high-profile dialogue with an entrenched atheist remains unparalleled in papal texts. Even the philosopher-pope St. John Paul II did not address Nietzsche, preferring instead to discuss thinkers such as René Descartes or Paul Ricoeur when the opportunity arose. (During his short papacy, however, Pope John Paul I did anticipate Benedict by mentioning Nietzsche in a Wednesday audience devoted to Christian hope.)

Benedict, the theologian-pope, finds in Nietzsche a privileged interlocutor, and the ensuing dialogue affords him the welcome opportunity to formulate clear and compelling answers to the crucial questions of our times. We who wonder how to dialogue effectively would do well to follow his example.

The beatitudes are not opposed to the enjoyment of life; rather, they take us beyond the superficial appreciation of life to expose us to its vital depths.

Unlikely interlocutors

In “Deus Caritas Est” (2005), Pope Benedict gets to the heart of love by first citing Nietzsche’s aphorism in Beyond Good and Evil concerning sexual love: “Christianity gave Eros poison to drink; he did not die of it but degenerated—into a vice.” Nietzsche here expresses what the pope calls “a widely-held perception” that somehow Christianity destroys the very highest aspect of human existence in its insistence on the purity of love.

Yet Benedict says that even the Greeks were well aware of the temptation inherent in sexual love, a temptation already identified in the Old Testament, and this is a temptation to dominate and use another human being for passing pleasure. Christianity, we could say, did not poison but rather healed love so that it could become what it is meant to be: the highest affirmation of being, the expression of our profound freedom and a vehicle of divine blessing.

In Jesus of Nazareth (2007), Pope Benedict pauses in the midst of the beatitudes to consider Nietzsche’s wholesale rejection of the ethic they propose as “a capital crime against life.” For Nietzsche, the beatitudes express a slave rebellion in morals that, out of resentment, calls what is good bad and what is bad good. On behalf of Nietzsche, Benedict asks, “Is it really such a bad thing to be rich, to eat one’s fill, to laugh, to be praised?” Just the year before he remarked: “It was said—I am thinking of Nietzsche but also of so many others—that Christianity is an option opposed to life. With the Cross, with all the Commandments, with all the ‘nos’ that it proposes to us, some have said that it closes the door to life.” Yet again Nietzsche presses the decisive question.

The beatitudes are not opposed to the enjoyment of life; rather, they take us beyond the superficial appreciation of life to expose us to its vital depths. Benedict points out, against Nietzsche’s criticisms, that even the Greeks recognized the temptation of hubris, “the arrogant presumption of autonomy that leads man to put on the airs of divinity, to claim to be his own god, in order to possess life totally and to draw from it every last drop of what it has to offer.” Against such a temptation, Benedict offers the powerful witness of Christ and the saints whose “yes” to love reveals the true content of human happiness. Here there is no inversion of good and bad but instead the humble opening of oneself to a still greater good: participation in the overflowing life of God.

Benedict welcomes Nietzsche’s criticisms because they afford the opportunity of making the truth of the matter more manifest.

In his encyclical devoted to hope, “Spe Salvi” (2007), Pope Benedict turns to the other great modern critic of Christianity, Karl Marx. His materialism, argues Benedict, imprisons us in a frame of reference that naively excludes both our deepest aspirations for unconditional love and our propensity for radical evil. While there is no mention of Nietzsche, Benedict does elsewhere note his challenge on this front:

As Nietzsche said: ‘The great light has been extinguished, the sun has been put out’. … But the big problem is that were God not to exist and were he not also the Creator of my life, life would actually be a mere cog in evolution, nothing more; it would have no meaning in itself.

Absent a transcendent source of existence and of love, there is no hope of meaningful progress, and we remain bereft of what Spe Salvi calls “the great hope that sustains the whole of life.”

In “Lumen Fidei” (2013), Pope Francis offered as his first encyclical the last one drafted by Pope Benedict. Again, Nietzsche appears at the very outset to speak as the mouthpiece of “many of our contemporaries,” who are proud of modernity’s autonomous rationality and who regard faith no longer as an illuminating light but instead a kind of enveloping darkness.

The two popes write: “The young Nietzsche encouraged his sister Elisabeth to take risks, to tread ‘new paths…with all the uncertainty of one who must find his own way’, adding that ‘this is where humanity’s paths part: if you want peace of soul and happiness, then believe, but if you want to be a follower of truth, then seek.’” The whole encyclical takes as its task rekindling the sense that faith reveals the breadth and depth of human existence and thereby restores to life a genuine spirit of inquiry and adventure: “Religious man is a wayfarer; he must be ready to let himself be led, to come out of himself and to find the God of perpetual surprises.”

Benedict defends the Christian form of life, constituted by love, hope, faith and the beatitudes, in the face of Nietzsche’s unsparing criticisms.

If modernity is defined by immanent rationality and irrational religion, Pope Benedict offers the post-modern synthesis of transcendent reason and reasonable religion.

Dialogue and truth

In “Deus Caritas Est,” Benedict recalls how the materialist philosopher Pierre Gassendi would greet René Descartes by saying, “O Soul,” and Descartes would reply, “O Flesh.” Why did Pope Benedict find it worthwhile to converse with such a thinker as Friedrich Nietzsche? What comes of the exchange “O Crucified” and “O Dionysus”?

Aristotle writes that we should be grateful to those who express views other than our own, even if those views are superficial, because they prompt us to inquire into the truth in fresh ways and to articulate reasons in support of what we know to be true. The point of such a dialogue is in fact not necessarily to change the interlocutor’s mind but instead to bring to light the intelligibility of one’s own position for those who witness the exchange.

In the same way, Benedict welcomes Nietzsche’s criticisms because they afford the opportunity of making the truth of the matter more manifest. Their dialogue concerns not just Christianity but indeed the question of the vitality of contemporary rationality and life; nothing less than truth itself is at stake.

Dialogue or dia-logos, Benedict says in “Caritas in Veritate” (2009), is rooted in rational speech, or logos, thanks to which we can both apprehend and communicate the truth to one another: “Truth, by enabling men and women to let go of their subjective opinions and impressions, allows them to move beyond cultural and historical limitations and to come together in the assessment of the value and substance of things. Truth opens and unites our minds in the lógos of love: this is the Christian proclamation and testimony of charity.”

Nonetheless, Nietzsche says that Beyond Good and Evil is not so much directed against Christianity, which has lost its sway over the West, but instead against modernity, because he thinks it has led to a mediocre, life-denying way of being. For him, the modern state is in some ways a secularized version of Christianity that retains all of its problems without any of its charms. (For example, he contrasts the noble piety of the poor with the insolence of the bourgeoisie, for whom nothing is sacred.)

He says he offers “a critique of modernity, not excluding the modern sciences, modern arts, and even modern politics, along with pointers to a contrary type that is as little modern as possible—a noble, Yes-saying type.” Reason, for him, is nothing more than a utilitarian calculus that robs life of its grandeur, and even the concept of truth must yield to the most powerful perspectives. Rejecting rationality and embracing, exuberantly, the language of the heart, Nietzsche looks to Dionysus as his model.

Benedict, for his part, thinks modernity suffers principally from an insensitivity to truth, which Plato calls “misology” or hatred of logos, and he challenges modernity to regain its love of logos and of the truth that transfigures us. To this end, he calls for a self-critique of modernity, involving, in equal measure, a critique of modern reason and of modern religion.

In “Caritas in Veritate,” Benedict writes:

Secularism and fundamentalism exclude the possibility of fruitful dialogue and effective cooperation between reason and religious faith. Reason always stands in need of being purified by faith: this also holds true for political reason, which must not consider itself omnipotent. For its part, religion always needs to be purified by reason in order to show its authentically human face.

If modernity is defined by immanent rationality and irrational religion, Pope Benedict offers the post-modern synthesis of transcendent reason and reasonable religion. Nietzsche may have railed against modern rationality and thereby helped to usher in our period of hostility to reason, but Benedict offers us an alternative to both modern rationalism and contemporary irrationalism. In this way, his exemplar is the “Crucified One,” the logos made flesh, who unites in his own person both the mind and the heart.

The question of Dionysus or the Crucified is also the question concerning the very possibility of meaningful dialogue today. Nietzsche advocates abandoning modern reason and modern faith, while Benedict advocates expanding and purifying modern reason and modern faith. Can contemporary reason become self-critical in a healthy manner in order to regain the possibility of achieving truth concerning ultimate questions? Can we learn again how to dialogue about the things that really matter?

Nietzsche may have helped to usher in our period of hostility to reason, but Benedict offers us an alternative to both modern rationalism and contemporary irrationalism.

Touched by God

Nietzsche first visited Rome and St. Peter’s in April 1882. Emerging from the meandering medieval streets into Bernini’s magnificent open colonnade, he strode into a resplendently decorated interior, which includes still more masterpieces by Bernini: the triumphant baldacchino over the tomb of the first pope and the imposing statues of four doctors of the church holding up the chair of St. Peter, bathed in the warm alabaster glow of the Holy Spirit window.

Nietzsche, we know, met his friend, Paul Rée, who sat in an unused confessional booth poring over his papers. Seemingly unaffected by the beauty around him, Nietzsche famously said: “From what stars have we fallen to meet here?”

The following year Nietzsche spent some lonely months in Rome. He laments in Ecce Homo about the impossibility of finding an anti-Christian quarter in a city full of churches before eventually settling on the Piazza Barberini. There, one dark night, moved by the plashing of Bernini’s inspiring fountain far below, Nietzsche wrote the “Night Song” that appears in Thus Spake Zarathustra. He identifies himself as the Dionysian artist in the centerpiece of the fountain, a magnificent, muscular Triton, a merman who blows water out of a conch shell held to his lips. The poem broods mischievously and bitterly on the loneliness of the poetic creator who gives his readers meaning and receives nothing in return.

Pope Benedict regularly extolled two masterpieces by Bernini: the majestic colonnade of St. Peter’s that reaches out in an ideal expression of welcome to believers and all people of goodwill, and the chair of St. Peter in the apse of the basilica. Of the latter, he ruminates, “True faith is illumined by love and leads towards love, leads on high, just as the altar of the Chair points upwards towards the luminous window, the glory of the Holy Spirit, which constitutes the true focus for the pilgrim’s gaze as he crosses the threshold of the Vatican Basilica.” Benedict sees in that window, with its vibrant Baroque rays and cherubic faces, a powerful representation of the “overflowing fullness that expresses the richness of communion with God.”

For Benedict, Bernini’s masterpiece, like Mozart’s “Requiem” or Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, offers a sort of confirmation of the truth of Christianity. “Christian art is a rational art—let us think of Gothic art or of the great music or even, precisely, of our own Baroque art—but it is the artistic expression of a greatly expanded reason, in which heart and reason encounter each other.” The convergence of heart and reason in the openness to beauty and truth constitutes the fundamental Christian challenge to the sterile immanence of so much of modern culture and life. By means of such art, the church “has the task of opening up, beyond itself, a world which tends to become enclosed within itself, the task of bringing to the world the light that comes from above, without which it would be uninhabitable.” (See Pope Benedict’s homily from Feb. 19, 2012.)

Who among us is not nostalgic for joy? Our world has lost its faith and hope in love, and reason, anemic reason, seems unable to help. Can joy come to us through Nietzsche’s Dionysus and his rejection of instrumentalized reason? Or can joy come to us through Benedict’s Crucified Christ and his revitalized reason? That is the question put to those of us who witness the dialogue between these two German thinkers, one a philosopher and the other a pope. Perhaps not surprisingly, it is the pope who puts more faith in reason.