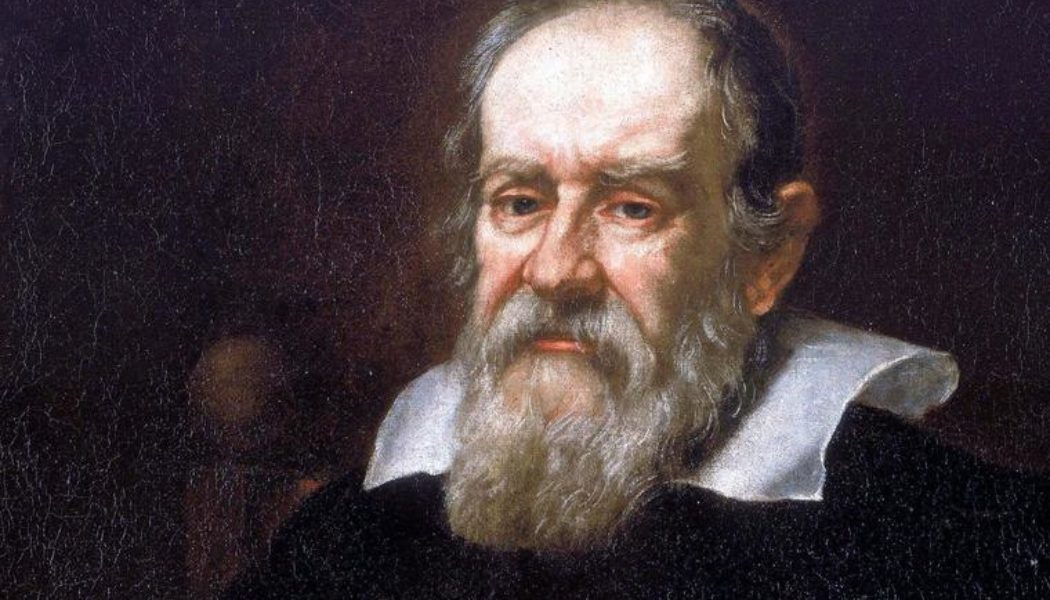

Galileo did not prove that the Earth moves. He did not invent the telescope. He was not excommunicated, tortured or burned. So where do these ideas originate?

We got “Galileo hate mail” here at the Vatican’s astronomical observatory. It was funny — and not funny. It originated, and originates, in respectable places. And it speaks to the broader problem of truth today.

The “mail” was social media comments. This spring our new web site, VaticanObservatory.org, received some media coverage (the National Catholic Register covered it). That coverage brought us to the eyes of some who could not reconcile the Vatican Observatory’s centuries of scientific work with the story of Galileo. They left comments claiming that Catholics used to “barbeque” people for doing science, and so on.

It was funny in that these confident commenters were so misinformed. We heard that Galileo invented “the first space telescope,” that the Church burned Copernicus at the stake — and Galileo, too, and tortured and excommunicated him, and so on. But it is never truly funny to see people confidently spouting misinformation. It is all the less so because misinformation is so common today.

In the case of Galileo, it is easy to see why misinformation abounds. In children’s books, in books for tourists heading to Italy, even in grammar books, we can find it said that Galileo was persecuted by the Church for proving that the Earth moves, that he was excommunicated, and so on. But Galileo did not prove that the Earth moves. He was not excommunicated. He did not invent the telescope. He was not tortured, not burned, and neither was Copernicus. So where do these ideas originate?

Unfortunately, all too often they have originated with seemingly respectable, scholarly sources; who else would talk about a 17th-century scientist? Even recently a number of respectable-seeming books have been published that promote what Pope St. John Paul II once called the “myth” of Galileo:

- Harvard astronomer Avi Loeb’s 2021 book Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth, published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt — Loeb writes of Galileo having been tried for heresy by people who “refused to even look through his telescope,” and having been “forced to abandon his data and discovery” and recant.

- British historian Timon Screech’s 2020 book The Shogun’s Silver Telescope: God, Art, and Money in the English Quest for Japan, 1600-1625, published by Oxford University Press — Screech argues that the English sought to undermine Jesuit missionaries in Japan by taking a telescope there in 1611. Because the Jesuits taught astronomy to the science-hungry Japanese, he says, “a telescope would confuse and embarrass their whole mission” since “telescopes allowed any careful observer to see that Copernicus was correct” that Earth moves around the sun, contrary to the Jesuits.

- Popular author and astrophysicist Mario Livio’s 2020 book Galileo and the Science Deniers, published by Simon & Schuster — Livio argues that Galileo’s opponents were, as the title says, science deniers. He writes that Galileo was forced to abandon “what he regarded as the only possible logical conclusions in favor of what amounted to a seventeenth-century version of political correctness,” namely concern over conflicts with scripture.

This is all misinformation. Consider the “refusing to look through a telescope” idea. Maffeo Barberini — Pope Urban VIII — was the driving force behind Galileo’s 1633 conviction on suspicion of heresy. Barberini had been an admirer of Galileo. In 1620 he wrote a letter to Galileo, enclosing a poem he had written and referring to Galileo as “a brother.” The poem lauds Galileo’s telescopic discoveries, specifically the moons circling Jupiter and the spots on the sun.

But those discoveries did not show that Earth moved. Earth’s motion did not proceed logically from the available data. Telescopes did not enable any careful observer to see that Copernicus was correct.

The books listed above contain errors, some quite basic, despite all the resources available to, for example, a Harvard author, or an Oxford publisher. How can this happen? Perhaps because we know today that Earth does move, and because the Galileo myth is so familiar. No one considers that Earth’s motion might not have been scientifically obvious in Galileo’s time.

And, the Church, and especially Urban VIII, is the bad guy in the Galileo story. Galileo’s former “brother” turned against him — for uncertain reasons, Urban went from lauding Galileo in poetry to exploding in rage at the mention of his name. Galileo was not tortured or burned, but he was put under house arrest.

Yet in Galileo’s time, people were subject to the cruelest punishments for relatively petty crimes. London Bridge bristled with the heads of executed criminals, impaled on poles. Slavery was being introduced to the New World. Given such a cruel time, why is the hounding of a scientist with powerful friends so notorious?

Probably because the Galileo myth derives its strength from the idea that he was persecuted over science. Thus, understanding the science of the time matters. Whether Galileo was logical in supporting a moving Earth, whether his opponents were science deniers, whether anyone with a telescope could see that Earth moves — judging these questions requires first digging into science as it was in Galileo’s time, not just repeating old myths.

Do we want truth, or myths? Do we want to really learn what is true and what is not, or do we merely wish to confirm what we already know so we can toss it around on social media? If all we want is a toss-able story about Galileo proving that the Earth moves and being brought down by a cabal of powerful men who would not even look through a telescope and see for themselves that he was right — then respectable books repeating myths are no problem. Nor, really, is any of the other misinformation that abounds today.

But Catholics must seek truth. That is one reason the Vatican supports an astronomical observatory and thus participates in the search for scientific truths. So there is nothing funny about the Galileo myth. There is nothing funny about misinformation.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity