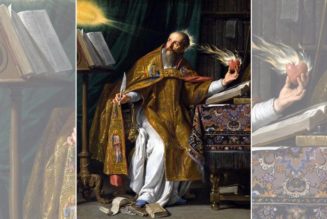

Some people think a Catholic intellectual is something like a waterproof towel, a screen door on a submarine, or an ejection seat on a helicopter, as Jonathan Swan quipped. These people must have forgotten about the long list of Catholic intellectuals, from Augustine and Aquinas in the premodern world, Leonardo da Vinci and Thomas More in the Renaissance, and Elizabeth Anscombe and Alasdair MacIntyre in our own times.

It is always surprising to me that nonbelievers sometimes posit that the life of faith shuts down the inquiring mind. In fact, faith does not dampen the desire to know, but inflames it. Thomas Aquinas pointed out that “the knowledge of faith does not set the desire at rest, but inflames it because everyone desires to see what he believes.” Catherine of Siena put the point even more emphatically:

“You [God] are a mystery as deep as the sea; the more I search, the more I find, and the more I find, the more I search for you. But I can never be satisfied; what I receive will ever leave me desiring more. When you fill my soul I have an even greater hunger, and I grow more famished for your light. I desire above all to see you, the true light, as you really are.”

Anyone who loves someone wants to know them better. So a person of faith who loves God wants to understand God, and to do that requires asking and answering questions about God. Every person of faith is to some degree a theologian, to some degree a Catholic intellectual.

Likewise, having faith does not shut down questions, for asking questions is part of the job of the Catholic intellectual. In his Summa theologiae, St. Thomas asks more than 2,667 questions, including the most fundamental: “Does God exist?” Indeed, having faith does not shut down asking questions but rather gives rise to many new questions.

Daily Gospel Reflections

Bishop Barron’s Gospel Reflections straight to your inbox.

If you believe that God exists, you may then wonder why “Each new morn, new widows howl, new orphans cry, new sorrows strike heaven on the face,” as Shakespeare wrote in MacBeth. If you believe Jesus is true God and true man, then you might ask whether the child Jesus knew that decades later he’d be crucified, die, and rise? If you have faith that God loves everyone, and that Jesus is the incarnate Love of God, then you might ask why Jesus teaches difficult things like forgiving those who harm us?

A Catholic intellectual is a person in whom both faith and reason are operative in the journey toward deeper insight. Faith is operative because the Catholic intellectual accepts as true what God reveals, and reason is operative because the Catholic intellectual is committed to using reason to its fullest in order to come to greater understanding of all reality.

To be an intellectual is to ask deep questions and seek answers to those questions. Obviously, there are some Catholics who are not intellectuals, and some intellectuals who are not Catholics. But the Catholic intellectual is no more a contradiction in terms than the musical doctor or the athletic artist. Indeed, the musical doctor is a coincidence of two identities that are not essentially related. By contrast, there is an inherent tie between being a Catholic and being an intellectual. If Jesus is himself the truth (John 14:6), and if the Church is the pillar and foundation of truth (1 Tim. 3:15), then the Catholic intellectual has an advantage in seeking the truth which is not possessed by the non-Catholic intellectual.

So, a Catholic intellectual develops not only her reason but also her faith. And faith is developed in part by practice. My faith began to develop in fourth grade. I got trained to be an altar server by a fifth grader I looked up to named Mark. Witty and charismatic, he was the best pitcher on our baseball team and also a great basketball player. I put on the server’s alb for the first time, and Mark directed me to walk across the sanctuary in front of the altar as if it were my first Mass.

“Man, what are you doing?!” he chastised me.

“Just walking out like at the start of Mass,” I meekly replied.

“Well, you look like you are walking on a baseball field. What’s wrong with you? Show some reverence and respect.”

He told me to get my act together. Sit statue still. Focus on what is happening. Remember the Mass is holy, so act like it. That a fifth grade boy like Mark took serving Mass so seriously, made me think about the importance of Mass in a new way.

Inspired by Mark, I served my first Mass and many subsequent Masses as reverently as I could. As I began to serve Mass, I began to appreciate the dignity and beauty of the Mass, which made me better appreciate the dignity and beauty of God. The Catholic intellectual seeks not just the true, but also the beautiful. “If you would believe,” wrote Fr. Richard John Neuhaus, “act as though you believe, leaving it to God to know whether you believe, for such leaving it to God is faith.” Acting with greater reverence at Mass helped strengthen my faith.

In the fourth grade, I also ran across a box of my mom’s college books upstairs in the attic where I wasn’t supposed to rummage around. I opened Introduction to Aquinas, filled with texts from Thomas himself. The book began with a question: “Is theology a science?” Although I could understand each word individually, I could hardly understand a single sentence that followed. I found Aquinas almost completely unintelligible. Years later, I would write Thomas Aquinas on Faith, Hope, and Love: A Summa of the Summa on the Theological Virtues and Thomas Aquinas on the Cardinal Virtues: A Summa of the Summa on Justice, Courage, Temperance, and Practical Wisdom because these are the books I wish I had found as an introduction to Aquinas.

Another book from the box, I Teach Catechism, was more accessible. It pointed to the great minds of the Church—Ambrose, Augustine, Chrysostom, Aquinas, Newman—and noted that they had questions, difficulties, struggled to find answers, and remained faithful. So we can have confidence that whatever questions we have, drawing on our 2000-year tradition (even more if you count the Jewish minds of the Old Testament), we can think through these questions. “Every now and then someone boasts, ‘I have an absolutely new idea.’” Bishop Fulton Sheen replied, “Go back and see how the ancients put it. Very often we call something modern because we do not know what is ancient.” My confidence in the Catholic tradition has something to do with recognizing my limitations. I know I am not half as wise as an Augustine of Hippo or a Thomas Aquinas or a Fulton Sheen, so if they could work within this tradition, so can I.

Catholic intellectuals, to be effective, must have knowledge of faith as deep as their other knowledge. If Catholic lawyers, doctors, or professors have an understanding of their faith no more advanced than a grammar school student, such people will have trouble reconciling their religious faith and their secular reason. Catholic intellectuals need a developing understanding of the truths of faith that is proportionate to their understanding in their professional field.

And that development is an ongoing process. A good lawyer realizes that the law is a deep, complex, and developing body of knowledge and so she continues learning. A good doctor does not leave learning behind after medical school graduation but seeks continuing medical education. And a good Catholic loves God with his or her whole heart, soul, strength, and mind. That ongoing spiritual and intellectual development is the vocation of a Catholic intellectual.

Join Our Telegram Group : Salvation & Prosperity