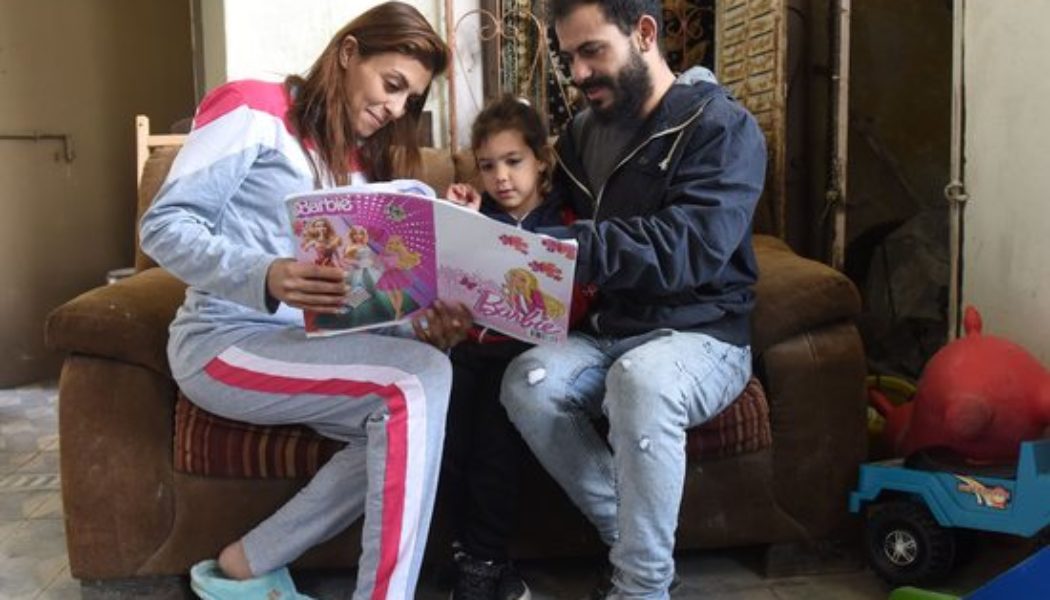

Parents are pictured in a file photo reading to their daughter. Before Google and especially before AI, there were these things called parents, and children would go to them with questions, and things like conversations and learning and families would be built upon them.

” data-image-caption=”

Parents are pictured in a file photo reading to their daughter. Before Google and especially before AI, there were these things called parents, and children would go to them with questions, and things like conversations and learning and families would be built upon them. OSV News photo/CNS file, Debbie Hill

” data-medium-file=”https://i0.wp.com/thecatholicspirit.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/TECHNOLOGY-PARENTS-EXPENDABLE.jpg?fit=300%2C202&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i0.wp.com/thecatholicspirit.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/TECHNOLOGY-PARENTS-EXPENDABLE.jpg?fit=550%2C370&ssl=1″ decoding=”async” class=”size-full wp-image-114886″ src=”https://i0.wp.com/thecatholicspirit.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/TECHNOLOGY-PARENTS-EXPENDABLE.jpg?resize=550%2C370&ssl=1″ alt=”Parents are pictured in a file photo reading to their daughter. Before Google and especially before AI, there were these things called parents, and children would go to them with questions, and things like conversations and learning and families would be built upon them.” width=”550″ height=”370″ srcset=”https://i0.wp.com/thecatholicspirit.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/TECHNOLOGY-PARENTS-EXPENDABLE.jpg?w=550&ssl=1 550w, https://i0.wp.com/thecatholicspirit.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/TECHNOLOGY-PARENTS-EXPENDABLE.jpg?resize=300%2C202&ssl=1 300w” sizes=”(max-width: 550px) 100vw, 550px” data-recalc-dims=”1″>

Parents are pictured in a file photo reading to their daughter. Before Google and especially before AI, there were these things called parents, and children would go to them with questions, and things like conversations and learning and families would be built upon them. OSV News photo/CNS file, Debbie Hill

About 10 years ago, my younger son stopped me in my tracks with a thoughtful observation.

I wasn’t surprised that he could be thoughtful — he often is — but this time his thought seemed momentous to me: “Parents don’t get to teach their children anymore. When I was little,” he explained, “if I wanted to know almost anything, my first instinct was to go to you or Dad about it: ‘What’s a bowline knot? Why does everything get dusty? What is a shillelagh?’ We would always talk it through. Now, if I’m curious about something I just go to Google. Younger kids don’t even develop the habit of going to their parents for answers. They’ve been googling since they could reach a keyboard.

“Parents have become expendable,” he concluded. “They aren’t even in the equation.”

He went about his business unbothered. I, on the other hand, spent the rest of the day in a horrified sort of daze. Pondering just how numerous and fruitful were the meandering conversations that fill our lives, I realized my son had identified a real threat to ordinary family dynamics. Our children’s questions often became openings not just for discussion but for mutual learning and creative engagement. If my husband or I could not answer something off the top of our heads, we’d join in the research — searching a dictionary or an encyclopedia with them, or heading to the library if that’s what was required. We learned together, and more than once a child’s question turned into a personal or family project.

Did you ever notice that in a jar of mixed nuts the cashews and Brazil nuts are always on top while pistachios and broken pieces are on the bottom? One son noticed and asked about it. Soon we were putting rocks of varied sizes into a can and shaking it, finding that — what do you know — smaller things sink to the bottom as space availability relegates bigger stuff to the top. This wasn’t an earth-shaking realization (although one son eventually used it for a grade-school science project to good effect), but the question sparked discussion and then activity. In varying degrees, the whole family participated in the discovery and together we managed to be curious, entertained, informed and — perhaps most important — impressed with each other.

It’s a slight thing, yes, but — as our little experiment demonstrated — small things are what the big things ultimately rest upon. Family structure, sibling reliance, mutual respect, parental humanity and vulnerability — all of that big stuff rests upon the little questions and answers, the ever-widening discussions, the trivial but sweetly recalled moments of shared exploration and curiosities satisfied. Going to a search engine for an answer might be expedient but it delivers none of that vibrant interaction. A question quickly resolved brings no encouragement to throw a curve into one’s thinking, or to puzzle out new ideas while laughing or maybe even crying, if that’s where the human part of it leads.

These memories came rushing back to me thanks to news stories about artificial intelligence and an AI tool called ChatGPT — GPT stands for “Generative Pre-trained Transformer” — which can write lively, human-sounding speeches, poems and school papers. Recently Rep. Jake Auchincloss, D-Mass., took to the House floor and delivered a 100-word speech written by ChatGPT; anyone listening would never have suspected it wasn’t written by a human. In an “explainer” article, the Associated Press actually asked the tool how to discern its writing from human work and was given a perfectly reasonable response. The article then noted, “Open AI said in a human-written statement this week that it plans to work with educators as it learns from how people are (using) ChatGPT … .” Increasingly, we will see distinctions between human and machine-generated material become required, if we’re to keep the world honest. For a while, anyway.

Our children learn from their parents and the world around them — how humans speak, act, explain, think, hold and uphold. Artificial intelligence learns, too, from what it is purposely or unwittingly fed by the human element. But it has no limits and no boundaries; it is an empty vastness, offering no human consolations, upholding nothing.

How terrifyingly bleak and unholy that sounds.

Elizabeth Scalia is culture editor for OSV News.

Category: Featured, U.S. & World News